Postcards from the future: the river-cleaning Birrabot. REALMstudios/NGV Australia

The Ian Potter Centre at Melbourne’s Federation Square is located on the banks of the lower stretches of Birrarung, the Yarra River. For Reimagining Birrarung Design Concepts for 2070, on until 2 February 2025, the river flows into the gallery through ideas, images, objects and stories.

In this bold and unusual exhibition, we listen to traditional owners and get inside the imaginations of eight of Australia’s most innovative landscape architecture studios. By looking at “possible” and “preferred” futures, this exhibition frames the river as a complex, diverse, interconnected ecosystem that nurtures our health and is essential to human and non-human communities.

Urban rivers are being rethought internationally. In Australian cities, where big city rivers are often estuaries, the problems of waterways and wetlands are inseparable from colonisation and urbanisation. The fate of these cities as the climate heats up is tied to their rivers.

Melbourne was established in 1835 at the lower stretches of Birrarung where salt water from Port Phillip Bay travels about 10 kilometres upstream. Now metropolitan Melbourne dominates and influences the landscape of its lower reaches.

Rivers are Country

Entering the gallery, we are invited to listen to Birrarung. The river’s voice is spoken by Uncle Dave Wandin, Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung Elder and Birrarung Council member. Originally commissioned by the 23rd Biennale of Sydney, the video portrait provides an important transition from the bustle of Melbourne, into the contemplative space of the exhibition.

Many will know the river as the Yarra, or Yarra Yarra – but this was a mistranslation by a surveyor in the 1830s of another Aboriginal word Yarro Yarro, “it flows”.

The misnamed river has suffered from disconnection from its traditional owners and severe environmental degradation.

In 2017, the Yarra River Protection (Wilip-gin Birrarung murron) Act was passed by the Parliament of Victoria, to protect the river for future generations and to recognise the river and its lands as a single living and integrated entity. Uncle Dave Wandin is a member of the Birrarung Council, appointed to work with Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung Elders and communities, to provide independent advice to the government on the implementation of the Act.

Barracco and Wright’s contribution to the exhibition builds on the impact of this legislation. Speculative Policies displayed as an historic document from the future in a 2035 cabinet.

Installation view of McGregor Coxall’s design for reimagining Birrarung. NGV Australia/Photo: Sean Fennessy

Installation view of McGregor Coxall’s design for reimagining Birrarung. NGV Australia/Photo: Sean Fennessy

Colonial histories

Thinking about legislation in future worlds helps remind us the challenges of urban rivers – pollution, storm water management, and flooding – have colonial histories.

Waterways have long been treated as dumping grounds for Australia’s industrial progress.

In their work Aqua Nullius, not-for-profit multidisciplinary design and research practice OFFICE points to viticulture (winegrowing) and golf courses as culprits of water extraction in the Birrarung catchment.

The problems arise not only where water is redirected as a resource for elites, but also where the connections between waterways and wetlands are disrupted by roads, estates and colonial land use. Billabongs are cut off from their sources and creeks are converted to drains. Wildlife such as turtles, platypus and birds lose their habitat corridors.

Terra Nullius is well known as the concept that shaped colonists approach to Australia. Aqua Nullius, OFFICE argue, is just as significant. Rivers are country – and need to be respected, cared for and healed.

Designers from OFFICE assert the Terra Nullius concept applies to water too. NGV Australia/OFFICE

Designers from OFFICE assert the Terra Nullius concept applies to water too. NGV Australia/OFFICE

Seeing like a landscape architect

By combining ecological knowledge with architectural forms, landscape architects are often leading these goals alongside Aboriginal people. While many of Melbourne’s residents and visitors enjoy the outcomes of their designs in city parks and green infrastructure, landscape architects are rarely the focus of exhibitions in major art galleries. This exhibition shows how design projects can invite us to imagine urban rivers differently using a range of tools that bring life to possible futures.

In this exhibition we see images, maps, models, flags, plans, animations, timelines, and even a uniform design for a future “bio-zone guide”.

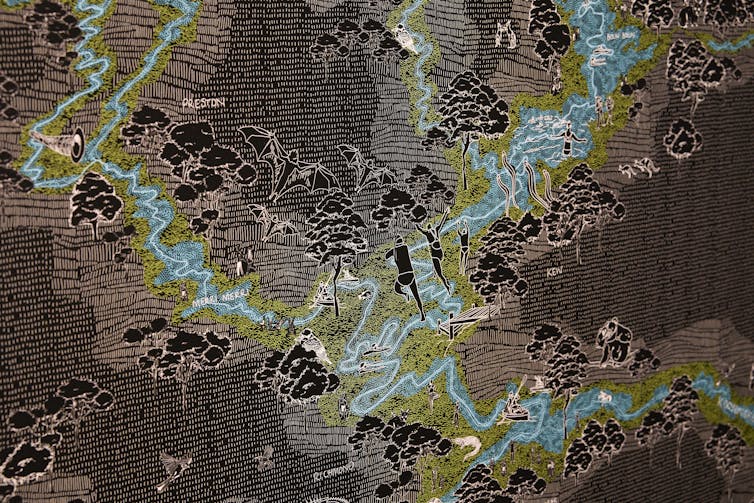

The Birrarung Catchment by McGregor Coxall projects an animated map at waist height. It shows us the past, present and potential future of the catchment, highlighting the evolution of Birrarung’s lands, health, waterways, and its relationship to people.

Presented as a map that shifts over time, the table top animation shares a rhythm with two screens on the wall, one with a population counter and one with the changes of flow within the catchment. These three elements link the growth of urban population to the disruption of the rivers flow. Dealing with Melbourne’s anticipated population growth, the projection looks forward in time proposing ways to care for the river by establishing the Great Birrarung Parkland.

What’s good for Birrarung …

Not all rivers are created equal. Melbourne is a river city, planned, designed, built and managed around Birrarung.

A short walk from the gallery, rowers launch into the river and lovers hold hands on its banks. Melbourne is Birrarung and we can see it as we move around the city. But all cities have waterways and wetlands, many less visible.

Place-based approaches to caring for urban water is needed everywhere. And this can have flow-on effects. If we start to care for minor creeks and estuaries that are built over and forgotten, we understand connections between people, nature, water and Country. This exhibition shows those visions for the future require research, vision and political will.

Reimagining Birrarung: Design Concepts for 2070 is on until 2 February 2025 at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia. Free admission.![]()

Alexandra Crosby, Associate Professor, School of Design, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.