Missy Higgins’ recent ARIA number-one album, The Second Act, represents an increasingly rare sighting: an Australian artist at the top of an Australian chart.

My recently published analysis of Australia’s best-selling singles and albums from 2000 to 2023 shows a significant decline in the representation of artists from Australia and non-English-speaking countries.

The findings suggest music streaming in Australia – together with algorithmic recommendation – is creating a monoculture dominated by artists from the United States and United Kingdom. This could spell bad news for our music industry if things don’t change.

Who dominates Australian charts?

In 2023, Australia’s recorded music industry was worth about A$676 million, up 10.9% year on year.

Building a strong local music industry is important, not only to support diverse cultural expression, but also to create jobs and boost Australia’s reputation on a global stage.

When Australian artists succeed, this attracts global investment, which in turn stimulates all aspects of the local music industry. Conversely, a weak music economy can lead to global disinvestment, thereby disadvantaging local companies, artists and consumers.

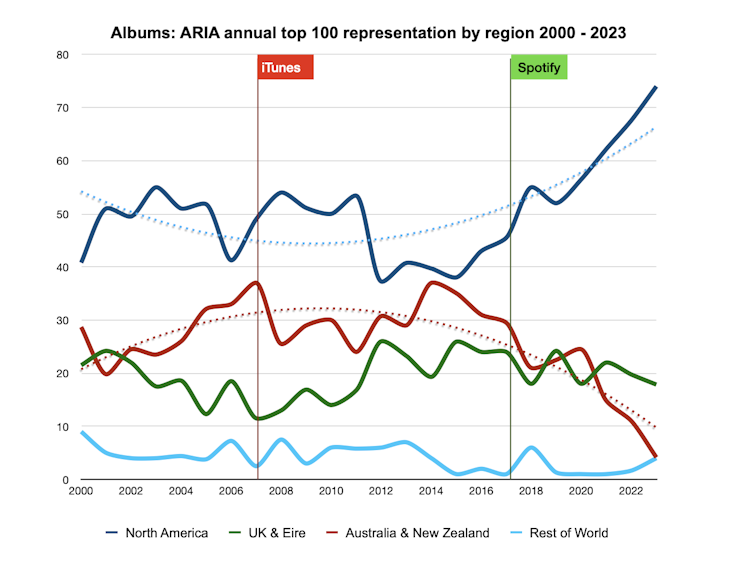

My research shows how the rise of music streaming – which became the dominant format for Australian recorded music sales in 2017 – has had a noticeable impact on the diversity of artists represented in the ARIA top 100 single and album charts.

In the year 2000, the top 100 singles chart featured hits from 14 different countries. By contrast, only seven countries were represented in 2023.

The percentage of Australian and New Zealand artists in the top 100 single charts declined from an average of 16% in 2000–16 to around 10% in 2017–23, and just 2.5% in 2023.

Album share also declined from an average of 29% in 2000–16 to 18% in 2017–23, and 4% in 2023.

This chart shows changes in diveristy in the ARIA top 100 albums chart over 22 years. Author provided

This chart shows changes in diveristy in the ARIA top 100 albums chart over 22 years. Author provided

Similarly, the proportion of artists from outside the Anglo bloc of North America, the UK and Australia/New Zealand declined from an average of 11.1% in 2000–16 to 7.3% in 2017–23 – while album share declined from 5% in 2000–16 to 2.3% in 2017–23.

My study also found representation of Indigenous artists remained low, but stable, over the period studied – and in line with population ratios.

Concentration of power

The findings suggest the decline in Australian and non-Anglo representation in the ARIA top 100 charts is linked.

Some economists and academics have argued easier access to independent music and global distribution via streaming will lead to greater diversity in music. But this hasn’t been the case in Australia, at least as far as chart-topping artists are concerned.

The global recorded music industry has consolidated in recent years. In the early 2000s there were five major music labels. Currently there are just three: Universal, Sony and Warner.

Last year, these three labels were responsible for more than 95% of the Australian top 100 single and album charts. Meanwhile, Spotify, Apple Music and YouTube make up an estimated 97% of the Australian streaming market.

These concentrations of power allow a handful of record labels and distributors to have a disproportionate influence over music design, production, distribution and governance – thereby limiting opportunities for diversity.

The need for new policy

My findings align with European research that found markets with a strong cultural differentiator of language are showing increased national diversity with streaming.

However, countries without a distinctive language are being increasingly dominated by global music production. In Australia’s case, we’re becoming reliant on the star-making machinery of the US.

Recently, Australia’s live music crisis came under scrutiny at a federal government inquiry, which highlighted the significant power imbalance between artists and multinational promoters.

As I and many others have suggested, targeted cultural policies are necessary to combat our highly concentrated and US-dependent market.

Relying on labels and streaming platforms will do little to preserve and promote our nation’s unique musical and cultural identity.![]()

Tim Kelly, PhD Candidate, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.