The Julius Baer Foundation’s transformative gift to the UTS Climate Change Cluster’s SEAweed Tech project is fast-tracking a social impact solution to a climate change problem by diversifying the income streams of coastal communities in the Philippines through zero-waste bioplastic production.

Building a biodegradable, bioplastic future

Distinguished Professor Peter Ralph, Executive Director of the UTS Climate Change Cluster.

In the Philippines, over a million coastal-dwelling people depend on fishing and seaweed for their livelihood, an increasingly vulnerable proposition in a changing climate.

When Nick Hill, co-founder and CEO of social enterprise Coast 4C, approached the team of scientists in the UTS Climate Change Cluster (C3) to collaborate on a sustainable farming solution for these remote marginalised communities, C3 Executive Director and UTS marine biologist Professor Peter Ralph knew it was a unique opportunity to make a difference – using science to tackle an income inequality issue and simultaneously mitigate climate change.

With some initial funding provided by the Swiss-based Julius Baer Foundation, the C3 team developed an efficient and inexpensive ‘green’ chemistry process to extract compounds from the red seaweed grown in the region and turn it into a bioplastic product.

“If we made these plastics in Australia, where's the social impact? Plastics are manufactured all over the globe,” explains Professor Ralph. “But by Nick bringing us these seaweed farmers in the Philippines that needed alternative income streams, it meant we had this already exciting social impact angle to what we were doing.”

Seaweed farmers gather their harvest north of Bohol Island in the Philippines (credit: Alamy)

The SEAweed Tech project is an elegant solution in myriad ways. By harnessing established large-scale seaweed farming and creating a sustainable, biodegradable bioplastic – whose manufacturing process produces zero waste – not only does it create local, future-proof employment opportunities for these communities, it also reduces overfishing, alleviates the environmental impacts of marine plastic pollution, and paves the way for ocean restoration.

In 2021, the Julius Baer Foundation increased their philanthropic interest in the project by making a transformative gift of $840,000. This enabled the team to take their ocean-positive, bio-based plastic from a successful concept testing phase to product development.

The synergy between the Julius Baer Foundation and the objectives of the SEAweed Tech project made this project a compelling proposition for a philanthropic foundation focused on advancing solutions to replacing plastics on our planet and reducing wealth inequality

“A research project must have the ability to change a situation of a people or environment,” says Julius Baer Foundation CEO Christoph Schmocker. “For us this was a clear solution, replacement-plastic project. The ultimate goal is to replace plastics with biodegradable plastics produced from a special seaweed that Philippine fishers cultivate instead of overfishing their oceans.”

For the team at C3 – who are dedicated to finding innovative solutions to progress Australia’s bio-economy and tackle the degradation of marine ecosystems – partnering with a philanthropic organisation rather than industry allowed them to accelerate through the development phase, turning a chemical extraction process into a usable bioplastic product with a wide range of applications.

“Thanks to the Julius Baer Foundation, we were able to grow the idea into a more compelling case, so we can take a fully realised product to industry,” explains Professor Ralph. “The grant has got us so far through the plastic production process and we’ve learned so many things along the way.”

Professor Peter Ralph with polymer chemist Lakshmi Krishnan inspect pellets created in the seaweed extrusion process.

As of March 2022, they have a bioplastic pellet they can take to market to ascertain which industry partners or consumers might want to use it for manufacturing purposes such as soft plastic products like packaging, or hard plastics like automobile interiors.

Eventually, in partnership with Coast 4C, the 3C team will move to setting up in-country production. The community-based supply chain business model will see local farmers grow the seaweed, dry the crop and bring it to a purpose-built facility in the village centre. Then villagers trained in the specific green chemical extraction process will undertake production, turning the seaweed into a bioplastic pellet. From there, the village will have a bulk quantity of pellets they can take directly to market, selling to a plastic manufacturer looking to purchase a bio-based plastic.

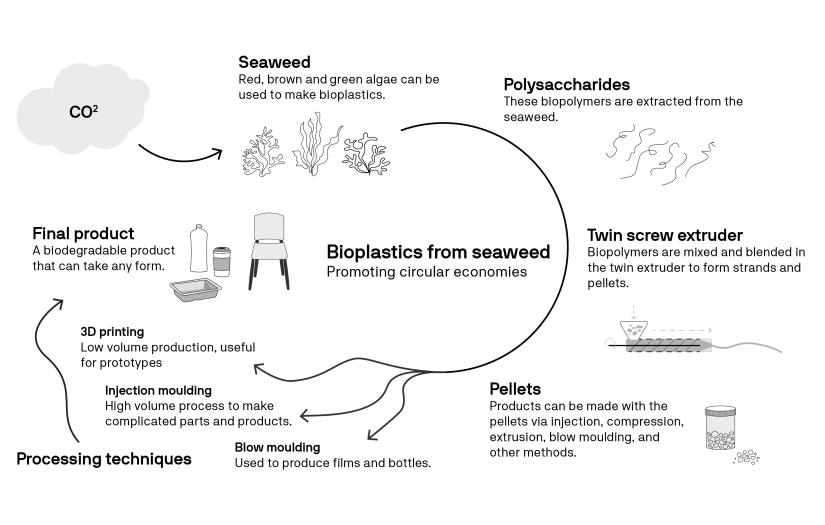

The seaweed biopolymer process to create usable bioplastics.

The speed at which this research project has advanced thanks to this philanthropic support has been exciting, comments Professor Ralph, and having the beneficiaries in mind right from the start that has been the driving force behind the project.

“Our production solution is supporting social equity in developing nations,” he says. “The goal is to avoid fishers and seaweed farmers selling their biomass into just one market, and this will empower them to have more control of their income streams.”

For Mr Schmocker, this clear-eyed view turns research into real social impact.

“If you can already see the community and talk with them and go home and say to your researchers, ‘Guys, we have to prioritise this because it is really key’, then it becomes inspirational,” he says. “Then the research team works with real people, responding to real people’s needs.

“And one of the unique features of this project is that it brings together the scientific expertise of the C3 team at UTS and the community engagement expertise of an NGO like Coast 4C, working together to ensure that this piece of research will deliver real outcomes.”

The need for coastal communities in countries of Southeast Asia to be supported with sustainable solutions like restorative seaweed farming has never felt more urgent than in the wake of the devastating Typhoon Rai that struck the Philippines in December 2021.

The super typhoon demonstrates exactly why we have to protect these communities, says Professor Ralph. The best way to do that is to reduce climate change and global warming, because these communities are at the front line. Every country is seeing evidence of this, but not to the same extent. And if at the same time we can support these communities through capacity-building to improve their social and environmental outcomes, then we’re really making an impact.

And considering the demand for bioplastics worldwide is “just unbelievably hot”, Professor Ralph and his team are excited by the possibilities for a not-so-distant future where ‘green’ bioproducts can increasingly help to fight climate change.

“This is the beginning of creating consumer goods that can decarbonise the atmosphere. We need to be providing society with these alternative bioproducts so they can vote with their wallets and select a product that is carbon-neutral or carbon-negative. We have this urgent need to develop technology for plastics, for carbon capture, for alternative proteins for food. We have to do everything we can to transform every industry that’s not sustainable.”