Colonisation, racism and chronic disease

Artwork by Lucy Simpson, Gaawaa Miyay Designs, gaawaamiyay.co.

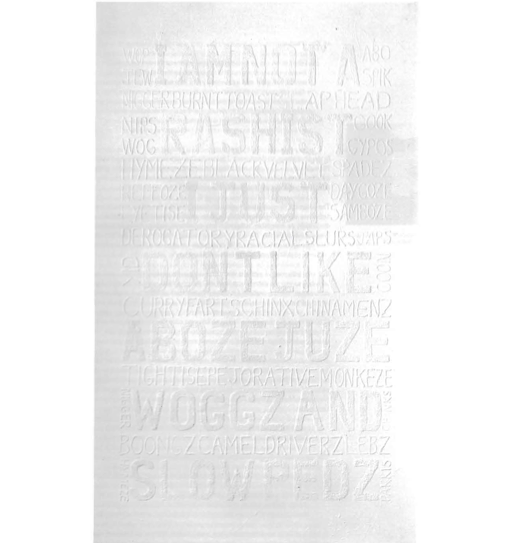

Types of racism

Racism is something all Indigenous Australians are familiar with. Health among human populations is a multifaceted and complex phenomenon. For Indigenous Australians racism is a fundamental driver of health and emotional wellbeing. Paradies et al (2008) presented three conceptual and interrelated levels of racism:

- Internalised racism: Acceptance of attitudes, beliefs or ideologies by members of stigmatised ethnic/racial groups about the inferiority of one’s own ethnic/racial group (e.g. an Indigenous person believing that Indigenous people are naturally less intelligent than non-Indigenous people).

- Interpersonal racism: Interactions between people that maintain and reproduce avoidable and unfair inequalities across ethnic/racial groups (e.g. experiencing racial abuse).

- Systemic racism: Requirements, conditions, practices, policies or processes that maintain and reproduce avoidable and unfair inequalities across ethnic/racial groups (e.g. Indigenous people experiencing inequitable outcomes in the criminal justice system). This type of racism is also referred to as institutional racism.

The 2014 ‘Stop. Think. Respect.’ campaign by Beyond Blue highlighted that ‘casual’ racism can be just as harmful as more overt forms.

Ongoing colonisation

In Australia, the link between racism and colonisation is paramount. European approaches to Indigenous Australians have been based on assumptions of their own Western worldview’s superiority (Sherwood, 2010). The prevalence of racism in Australian society today speaks to the ongoing practice of colonisation, manifested in oppression, persecution and marginalisation.

There are, though, more overt displays of colonisation evident today. According to Amnesty International, the ‘Stronger Futures Policy’ which has replaced the ‘Northern Territory National Emergency Response’ (often referred to as “The Intervention”), is a product of inadequate consultation with Aboriginal people living in the areas affected and fails to “recognise that local issues need local solutions rather than the failed one-size-fits-all Intervention policies that were imposed upon communities four years ago [1]”.

41% – Percentage of Australians who agree that “Australia is weakened by people of different ethnic origins sticking to their old ways”.

86% – Percentage of Australians who agree that something should be done to fight racism in Australia [2].

Evidence of health impacts

In dealing with racism and its effects, Indigenous Australians have been remarkably resilient. There is a body of work devoted to highlighting actions effective in coping with periodic and ongoing racism.

For experiences of chronic racism, it has been found that emphasising the positive and trying to change the situation is most effective; while for experiences of acute racism, emotional distancing is more effective (Clark, 2000). In addition, there are benefits in seeking social support (Krieger, 1990; Krieger & Sidney, 1996) and having a strong sense of racial identity/concept (Mossakowski, 2003; Sellers, Caldwell, Schmeelk-Cone, & Zinnerman, 2003; Williams, Spencer, & Jackson, 1999).

Racism leads to poor health

A three-year study by the Flinders University’s Southgate Institute in South Australia [3] reported that, experienced regularly, racism leads to poor health.

“We found that Aboriginal people do not primarily have a higher rate of illness because they lack knowledge of what behaviours are good for their health,” the study’s chief investigator, Dr Anna Ziersch said. “Compared with the general population, twice as many Aboriginal people did not drink and most exercised regularly—and yet they had worse physical and mental health.”

Pathways from racism to ill-health may include:

- reduced and unequal access to the societal resources required for health (e.g. employment, education, housing, medical care, social support);

- increased exposure to risk factors associated with ill health (e.g. differential marketing of dangerous goods, exposure to toxic substances (Krieger 1999));

- direct impacts of racism on health via racially motivated physical assault;

- stress and negative emotion reactions that contribute to mental ill health, as well as adversely affecting the immune, endocrine and cardiovascular systems;

- negative responses to racism, such as smoking, alcohol and other drug use, and;

- suicide.

There is good evidence that self-reported racism is associated with a range of adverse health conditions [4]. After accounting for the effects of a range of other contributing factors, racism was significantly associated with poor self-assessed health status, psychological distress, diabetes, smoking and substance use in the NATSIHS (Paradies 2007a) and with depression, poor self-assessed health status and poor mental health in the DRUID study (Paradies 2006b).

Preliminary findings from the Indigenous Urban Location and Health project show that racism in service provision and from neighbours and health staff is correlated with poor general health status (Gallaher et al. 2007), while a study in a rural Western Australian town demonstrated that racism was associated with reduced general physical and mental health after accounting for age, gender, employment and education (Larson et al. 2007). Racism was also associated with increased smoking, marijuana use and alcohol consumption in the WAACHS after accounting for the effects of age and gender (Zubrick et al. 2005).

Indigenous patients less likely to receive appropriate care

In Australia, it has been found that, compared to non-Indigenous patients with the same medical needs, Indigenous patients were about one-third less likely to receive appropriate medical care across all conditions (Cunningham 2002), as well as for particular diseases such as lung cancer (Hall et al. 2007) and coronary procedures (Coory & Walsh 2005). Indigenous Australians are three times less likely to receive kidney transplants than other Australians with the same level of need (Cass et al. 2004). These discrepancies in health outcomes point towards access issues caused by institutional racism.

The problem isn’t just access to health services, but it can also include experiences once inside the system. The stereotyping and problematizing of Indigenous Australians can lead to adverse treatment practices. Research by Cox (2007:7) found that “some hospital personnel allowed their fear and negative judgements to figure prominently in their clinical decision making… The assumptions made by health professionals about Aboriginal people’s use of alcohol contributes to high levels of morbidity through misdiagnosis and/or alienation of people from the hospital [5]”.

Patients avoid further treatment

A small study by the Menzies Centre for Health Policy [6] found cases of people so affected by racism by health workers that they eschewed further treatment.

"I’ve had some really bad experiences with doctors here and I’ve told my [AMS] doctor about them. He [the eye specialist] was a total pig, you know … it’s just the way that they talk to you. The way … they’re belittling you. Make you feel cheap and small and 'you’re wasting my time here'. You know? … He was really really rude and I mean he’s there to provide a service in a professional way and in a specialized area … he made me cry … no absolutely [I won’t] go back to him." ‘Participant G’ in the “People I can call on” study.

Experiences like the one above compound the suspicions many Indigenous Australians feel towards health services – that they are instruments of ongoing colonisation. Despite this, there are reasons for optimism. The recent National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey reported that only 4 per cent of Indigenous Australians indicated that they felt they were treated worse than non-Indigenous peoples, while 90% reported being treated the same and 6 per cent reported being treated better than non-Indigenous peoples (Paradies 2007).

Chapter References

[1] Amnesty International, Stronger futures in the NT must be a product of the people. 19 October 2011. Retrieved on 24 May 2013.

[2] ‘Challenging Racism’, research paper, University of Western Australia 2011.

[3] Gilbert Gallaher, Anna Ziersch, Fran Baum, Michael Bentley, Catherine Palmer, Wendy Edmondson, Laura Winslow, In our own backyard: Urban health inequities and Aboriginal experiences of neighbourhood life, social capital and racism

[4] Yin Paradies, Ricci Harris and Ian Anderson, The Impact of Racism on Indigenous Health in Australia and Aotearoa: Towards a Research Agenda, Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health and Flinders University, 2008

[5] Cox, L. (2007) Fear, Trust and Aborigines: The Historical Experience of State Institutions and Current Encounters in the Health System. Health and History 9, 1-13.

[6] Tanisha Jowsey, and others | Menzies Centre for Health Policy, 8 July, 2011.“People I can call on” Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander experiences of chronic illness.

Artwork

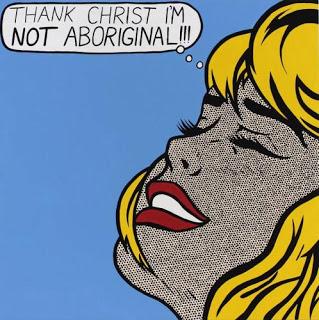

Aboriginal artists both record the effects of colonisation and racism while at the same time illustrating resistance and resilience. For example Jack Dale’s work portrays experiences from his childhood where Aboriginal men were imprisoned in Boab trees and people were bribed with lollies to make false accusations against each other. Other artists such as Richard Bell and Gordon Syron resist stereotypes of Aboriginal people and expose the racist behaviour and beliefs that exist in Australian history and society today.

UTS ART Education and Outreach Co-ordinator Alice McAuliffe and academic Jennifer Newman have produced a series of videos that explore the cultural and social contexts of Indigenous artwork from the UTS Art collection.

‘Civilised #13’ by Michael Cook

Photographer Michael Cook explores the subjectivity behind the word ‘civilised’, the title of his photo work. An Indigenous man dressed in an 18th century military uniform, sits casually on a horse at the water’s edge – the site of first contact between Indigenous and Non Indigenous Australians. A tri-corn hat on his head, he fingers a musket and appears relaxed and in his element. Yet he is in the milieu of a European soldier: a coloniser. What is civilisation? Is it about clothes, instruments, ‘fine’ implements and other superficial things, or is the artist suggesting that Western perceptions of what constitutes civilisation, misses the point?

Additional artwork

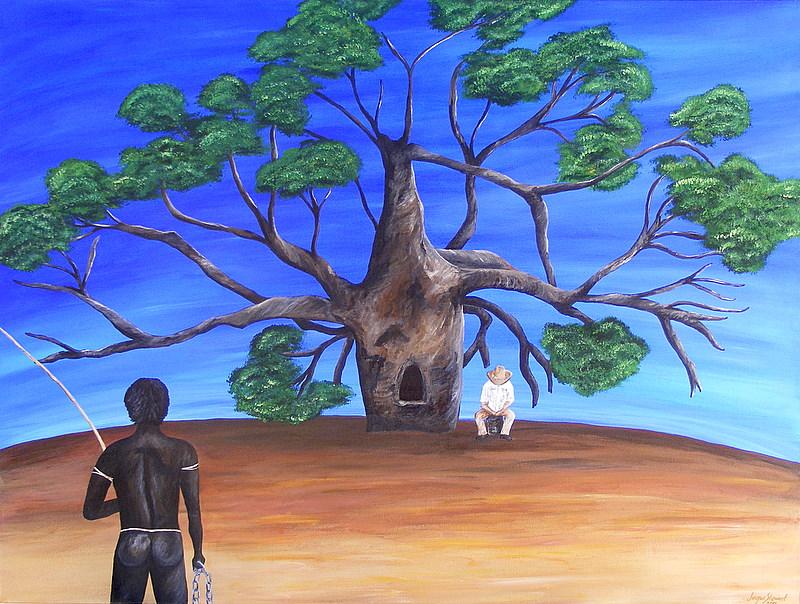

Hope Beyond the Window : a Stolen Generation by Jacqui Stewart. Image provided by the artist. jacquistewart.com.au

Prison Boab tree: chainless by Jacqui Stewart. Image provided by the artist. jacquistewart.com.au

Life on a Mission, by Richard Bell. Reproduced with kind permission of the artist.

The Peckin Order, by Richard Bell. Reproduced with kind permission of the Artist.

Aussie Aussie Aussie 2002, by Richard Bell. Reproduced with kind permission of the Artist.