Indigenous ways of knowing, being and doing

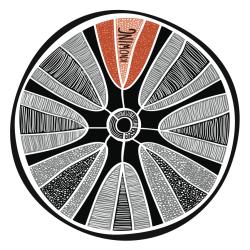

Artwork by Lucy Simpson, Gaawaa Miyay Designs, gaawaamiyay.co.

Value of Indigenous knowledges about health, wellbeing, family and community

The design of this resource pack utilises Indigenous Australians’ use of circles to illustrate the holistic nature of knowing, being and doing. The circle symbolises the collective strength of Indigenous culture. At its core, it may encompass whole communities, with concentric circles adding layers to the rich, vibrant culture.

To an Indigenous Australian, these concentric circles may represent country, Elders and ancestors. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation is now a requirement of health research involving Australian Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander communities.

Indigenous health academics have been involved in the production of this resource pack and contribute immensely to the teaching and research capabilities of the Faculty. In better understanding how Indigenous ways of knowing, being and doing can inform contemporary health practice it is important that Indigenous communities are not treated as research objects; Indigenous Australians must have a central role in decisions about what is researched and how it will be researched.

The disregard of Indigenous Australians’ ways of knowing, being and doing can be traced back to the false assertion of Terra Nullius – literally “land belonging to no one” in Latin – placed upon the east coast of Australia by James Cook in 1770. It took Eddie Mabo’s case in 1992 for the High Court of Australia to recognise native title in Australia for the first time.

Damaging assumptions

Despite this, the concepts underpinning the damaging myth – that Indigenous Australians’ relationship with land is temporary; there is no sense of connection, or ‘ownership’ – have endured in the mindset of many. More broadly, approaches to Indigenous Australians’ have been based on assumptions of the superiority of the Western worldview. This damaging assumption continues to influence the behaviour of institutions and individuals in their interactions with Indigenous people in Australia, most notably in the health and criminal justice arenas.

"Most non-Indigenous Australians’ educational experiences have promoted amnesic discourses of settlement fuelled by colonial assumptions of white superiority. This dominant way of knowing, being and doing has infiltrated all spectrums of mainstream society and it is this positioning that continues to promote problematic constructs of Indigenous Australians." Professor Juanita Sherwood.

This is important because it fails to acknowledge the deep connection to country experienced by Indigenous Australians, resulting in detrimental impact upon health, social and emotional wellbeing. It also ignorantly belittles the knowledges and ways of being and doing which have successfully sustained the oldest continuous set of cultures on the planet.

Indigenous Australians’ knowledges on health, wellbeing, family and community are broad and complex and little understood outside of their practitioners. The concept of Indigenous knowledge itself has life; it is ‘living’ knowledge, transmitted orally from its holders, often in the form of stories [1]. As such, it must be treated with care and respect, as one would any living entity.

More than just bush medicines

Indigenous health knowledges are more than just bush medicines. The continuance of culture, identity, tradition, custom, lifestyle, language, stories, songs, craft work, art, dance, rituals and ceremonies is crucial to Indigenous Australians. The stripping away of these elements of Indigenous identity is the root cause of many health afflictions faced by Indigenous Australians today.

Predominant western attitudes to Indigenous ways of knowing, being and doing suffer from ingrained bias borne of colonial paternalism, amounting to racism; heaping shame on those who rely upon its endurance for their social and emotional wellbeing. It need not be seen as a threat to western values and systems. The Indigenous ways of being in family and community abound in love, support and solidity of structure.

"The myth of terra nullius implied that this country was uninhabited and terra nullius social policy supported by research enabled for the dispossession of knowledges of Indigenous peoples. It must be remembered that university curriculum, teaching methodologies and research endeavours have a history of development that contributed to this dispossession. Has the time come for change?" Victor Hart & Sue Whatman, Decolonising the Concept of Knowledge Paper presented at the HERDSA conference, Auckland, 1998.

Principles of cultural safety: Institutional racism & bias

The strength and resilience of Indigenous Australians’ families is compromised by multiple complex problems, including historical and ongoing dispossession, marginalisation, and racism, as well as the legacy of past policies of forced removal and cultural assimilation (Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. (1997). Bringing them home: Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families (PDF, 19.3MB).

These issues contribute to the high levels of poverty, unemployment, violence, and substance abuse seen in many Indigenous communities. They also impact disproportionately negatively on Indigenous children, who demonstrate poor health, educational, and social outcomes when compared to non-Indigenous children.

Principles of cultural safety: Shaming by western attitudes

In delivering health services, practitioners often have to overcome low levels of trust, participation, social control, and efficacy, and high levels of anxiety, disempowerment, disorganisation, and mobility which have been built up from generations of poor practice. Lessons on service delivery can be learnt from the Practice Sheet developed by Communities and Families Clearinghouse Australia [2].

Central to this is moving away from an institutional agenda in health systems which perceive Indigenous Australians as ‘problematic’ and somehow shameful. This requires health systems to acknowledge the institutional and interpersonal racism exists within its own doors, impacting significantly on Indigenous health outcomes. This is the first step to changing practice.

Principles of cultural safety: Indigenous research paradigms

Valuing and respecting Indigenous ways of knowing, being and doing is the next step. To further develop health practice, providers should be open to collaboration with the great wealth of Indigenous health research practice. See, for instance, the work of Professor Juanita Sherwood in this area [3].

Chapter References

[1] Georgina Whap, A Torres Strait Islander Perspective on the Concept of Indigenous Knowledge, The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education. Volume 29, Number 2 (2001)

[2] Working with Indigenous children, families, and communities: Lessons from practice

By Rhys Price-Robertson & Myfanwy McDonald (in partnership with Peter Lewis & Muriel Bamblett of the Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency)

Published by the Australian Institute of Family Studies, March 2011, 7 pp. [ISBN 978-1-921414-36-7]

[3] Sherwood, J. Do No Harm: decolonising Aboriginal health research. Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of New South Wales.

Artwork

Aboriginal people lived in harmony with the land for thousands of years before colonisation. Having no written language, history, customs and morals were passed from generation to generation through story, song, dance and art. Jack Dale’s work describes Aboriginal spiritual beliefs, customs and traditions and hunting techniques.

UTS ART Education and Outreach Co-ordinator Alice McAuliffe and academic Jennifer Newman have produced a series of videos that explore the cultural and social contexts of Indigenous artwork from the UTS Art collection.

‘Mardayin Design at Milmilngkan’ by John Mawurndjul

Indigenous artist John Mawurndjul is internationally recognised for his contemporary work, often formed through masterful cross-hatching known as Rarrk. His art reflects his life on country in Milmilngkan, West Arnhem Land. John’s work, Mardayin Design at Milmilngkan, is inspired by the Mardayin initiation ceremonies for his people’s young men. It is a sacred and secret ceremony and therefore much of the Rarrk design associated with it cannot be shared with the wider public. Nevertheless, Mawurndjul’s work and the accomplishment of his technique, allows us an insight into the complexity of life and ceremony in Yolngu culture.

Additional artwork

Families Digging Honey Ants by Kathleen Buzzacot. Reproduced with kind permission of the Artist.

Jeff Roberts : Dreamtime. Image used with permission