Spirituality

Artwork by Lucy Simpson, Gaawaa Miyay Designs, gaawaamiyay.co.

Land and spirituality

Health professionals should be aware that spirituality is core to the health and emotional wellbeing of Indigenous Australians. In turn, Aboriginal spiritual beliefs strongly derive from the land people live on. It is ‘geosophical’ (earth-centred) and not ‘theosophical’ (God-centred).

Non-Indigenous people and land owners might consider land as something they own, a commodity to be bought and sold, an asset to make profit from, but also a means to make a living off or simply ‘home’. For Aboriginal people the relationship is much deeper. The land owns Aboriginal people and every aspect of their lives is connected to it.

"We don’t own the land, the land owns us. The land is my mother, my mother is the land. Land is the starting point to where it all began. It’s like picking up a piece of dirt and saying this is where I started and this is where I’ll go. The land is our food, our culture, our spirit and identity." S. Knight

Aboriginal law and spirituality are intertwined with the land, the people and creation, and this forms their culture and sovereignty. The health of land and water is central to their culture. Land is their mother, is steeped in their culture, but also gives them the responsibility to care for it. Living in a city has its own challenges.

"I often wonder how to connect with my country when I’m in the city, for many Indigenous people it’s a visceral connection; you look beyond the buildings and concrete and feel a sense of belonging." Francis Rings

Kinship

The system of kinship puts everybody in a specific relationship to each other as well as special relationships with land areas based on their clan or kin. These relationships have roles and responsibilities attached to them.

"It’s like the love for your mum and dad." Natasha Neidje

Kinship influences marriage decisions and governs much of everyday behaviour. By adulthood, people know exactly how to behave, and in what manner, to all other people around them as well as in respect to specific land areas. Kinship is about meeting the obligations of one’s clan, and forms part of Aboriginal Law, sometimes known as the Dreaming. Note that the Dreaming is not the product of human dreams. The use of the English word ‘dreaming’ is more of a matter of analogy than translation.

Aboriginal Law (the Dreaming)

"‘The Dreaming’ or ‘the Dreamtime’ indicates a psychic state in which or during which contact is made with the ancestral spirits, or the Law, or that special period of the beginning." Mudrooroo

The Dreaming also explains the creation process. Ancestors rose and roamed the initially barren land, fought and loved, and created the land’s features as we see them today. Each Aboriginal person identifies with a specific Dreaming. It gives people identity, dictates how they express their spirituality and tells them which other Aboriginal people are related to them in a close family, because they share the same Dreaming. One person can have multiple Dreamings.

My culture is my identity.

Dreamtime stories tell the life of my people.

Growing older.

Hearing stories of my ancestors living off the land

Becoming one with the creatures

Even though I haven’t met them

I feel this unbreakable connection

Through the stories I have heard.

The stories that have been passed down through generations.

These stories are living through us.

Without our culture we have no identity

And without our identity

We have nothing.

Poem by students Kiarra and Karri Moseley and Luke Bidner [1]

Christianity

Aboriginal spirituality has adapted over time and continues to do so. It can not only be changed by other religions, for example Christianity, but also by the environment Aboriginal people live in.

Dreamings now incorporate elements of Aboriginal life introduced since European colonisation, including western diseases and modern modes of transport. Christianity was first introduced to Indigenous people by missionaries, who often forced Biblical teachings upon the population, even as the Anglican Church took their land (the suburb of Glebe in New South Wales is so named because it was an area given to the church).

The fundamental tenets of Christianity are accepted by many Indigenous people today, especially by Torres Strait Islanders, and can be fused with Indigenous spiritual beliefs and values.

The Redfern Prayer

Pastor Ray Minniecon is an active leader in the Sydney Diocese of the Anglican Church. In 2009, he wrote what has become known as the Redfern Prayer.

God of our Dreaming. Father our all Aboriginal nations in Australia. You have lived among us since time immemorial. We have always known You. You gave this land to our Aboriginal nations. You have not dispossessed us nor destroyed us.

People from other lands, who do not understand our unique culture, our unique lifestyle and our unique heritage have come and destroyed much of our way of life. Many of these people from other lands now want to understand and reconcile with us.

But for many of us Aboriginal people, we find this reconciliation business a little difficult.

Too many of our children are still in jails.

Too many of our children are still living in sub-standard housing.

Too many of our mothers are living on the streets or in refuges.

Too many of our children are still uneducated.

Too many of our children have no land and no community to go back to.

Too many of our children have not got good opportunities for good employment.

Too many of our children are living in extremely unhealthy environments.

Too many of our children are living among violence and abuse.

Too many of our children are dying to drugs and other soul-destroying substances.

God our Dreaming and Creator of our people, we sometimes feel overwhelmed by these things. Many of us feel like we are refugees in our own land.

Today we are coming together again on one of our battlegrounds to cry out to You for mercy and justice for our children, for our families and for our land.

We pray that more resources will be given to our local community organisations to help us grow healthy and strong.

We pray that the peoples from other lands will be given a heart of flesh instead of a heart of stone so that they can understand us and support us properly.

We pray that your Spirit will help and encourage us to grow good strong Aboriginal leaders.

Father we want to grow strong and healthy again in our own land. We want to take our rightful place in our land and make our contribution to the re-building of our families, our communities and our nation.

Please hear our cries for justice. We ask these mercies in the name of Your Son.

Amen.

Pastor Ray Minniecon

Chapter References

[1] ‘Kempsey school celebrates culture’, Koori Mail 508 p.58

Artwork

Aboriginal spirituality stems from the dreaming which is temporally unbounded. The dreaming includes ancestors in both human and animal form who formed the land animals and people. Some of the spirits include the rainbow serpent who is associated with creation and water, the Biame who is a creationist spirit and Wadjinas who are rain Gods. Colonisation and the stolen generation however, has impacted significantly on Aboriginal spirituality with many Aboriginal people now embracing Christianity. Richard Campbells work draws parallels between Aboriginal beliefs and Bible stories for example.

UTS ART Education and Outreach Co-ordinator Alice McAuliffe and academic Jennifer Newman have produced a series of videos that explore the cultural and social contexts of Indigenous artwork from the UTS Art collection.

‘Salt on Mina Mina’ by Dorothy Napangardi

Salt on Mina Mina, the title of Dorothy Napangardi’s work, references the place where she was born – her country known as Mina Mina. Physically removed from there as a child, she eventually settled in Alice Springs and after many years started to paint. Her ancestral lands and the story of her family are prominent themes in her work. Much of that work consists of white dots on a black surface, which is a physical rendering of the ancestral songs Napangardi sang while working on a canvas,allowing her to keep country while not physically present on her country of Mina Mina.

Additional artwork

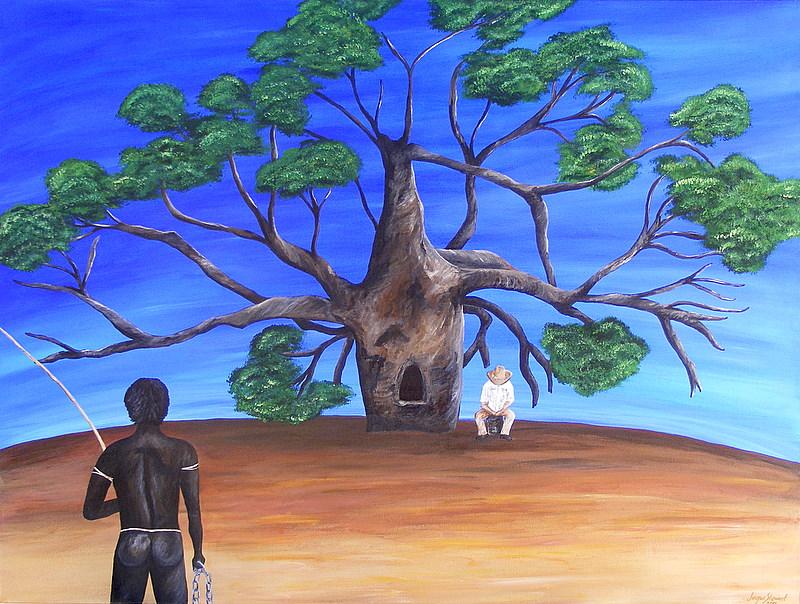

Prison Boab tree: chainless by Jacqui Stewart. Image provided by the artist. jacquistewart.com.au

Hope Beyond the Window : a Stolen Generation by Jacqui Stewart. Image provided by the artist. jacquistewart.com.au

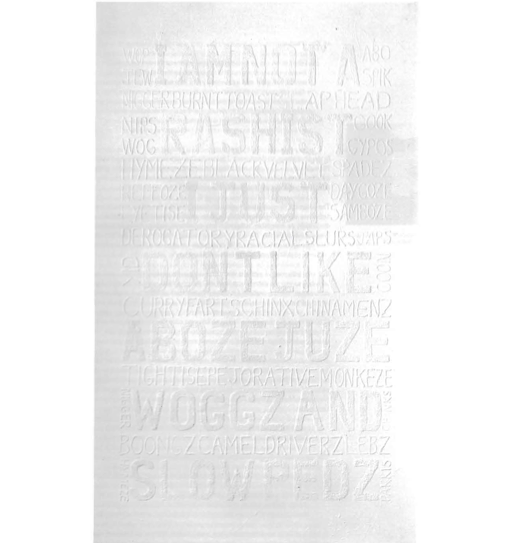

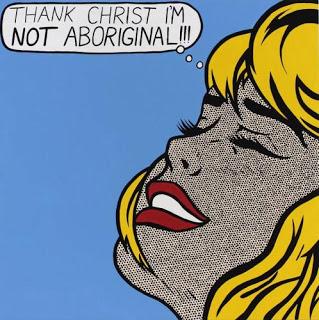

Life on a Mission, by Richard Bell. Reproduced with kind permission of the artist.

Aussie Aussie Aussie 2002, by Richard Bell. Reproduced with kind permission of the Artist.

The Peckin Order, by Richard Bell. Reproduced with kind permission of the Artist.