The case for boosting JobSeeker for all

Should people aged 55 and over get a targeted boost to their JobSeeker payments? Research suggests the need among young Australians may well be greater write Peter Siminski and Gianni La Cava.

Picture: Shutterstock

In response to calls to raise the JobSeeker payment, the Albanese government is expected to announce an increase in the budget only for recipients aged 55 and over.

Doing so will fuel the familiar generational debate about comparative levels of hardship experienced by older and younger Australians.

JobSeeker’s current single rate is $49.51 a day, about 65% of the age pension and 18.5% of average full-time earnings. Last month, the government’s own Economic Inclusion Advisory Committee recommended it be raised to 90% of the age pension.

This age targeting is reportedly justified on the basis that older recipients are more likely to be long-term unemployed, and majority female.

But are younger recipients less needy? Our research suggests their need may well be greater, reporting far higher levels of hardship than older Australians, even when depending on JobSeeker.

Measuring financial hardship

Our results are drawn from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey – better known as the HILDA survey – which each year since 2001 has polled a representative sample of about 18,000 Australians on many aspects of their lives.

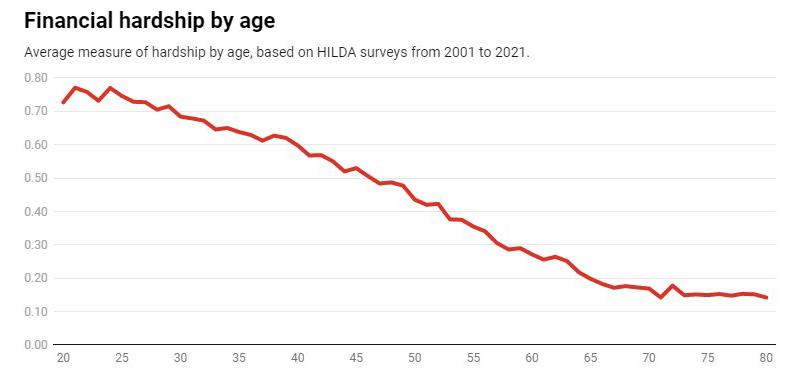

Our first graph shows average financial hardship by age.

We compiled this index from answers given by HILDA participants to seven indicators of their material hardship over the previous nine months. These were, due to a shortage of money:

- could not pay electricity gas or telephone bills on time

- could not pay the mortgage or rent on time

- pawned or sold something

- went without meals

- was unable to heat home

- asked for financial help from friends or family

- asked for help from welfare or community organisations.

About 22% of those aged 20-80 reported at least one hardship, with the average hardship of those in their 20s being 2.9 times more than those aged 55 to 69.

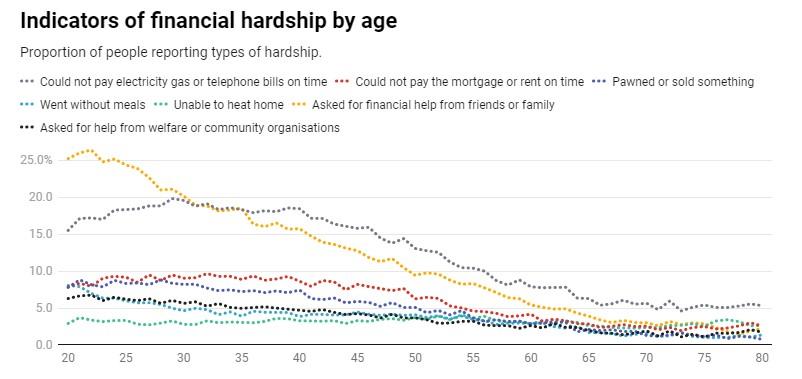

The next graph shows the constituent elements of the composite measure.

While the responses to “asking for help” – with young people presumably asking parents first – do seem to skew the results, five of the other six measures follow the same pattern. (The exception is “unable to heat home”, where there’s no significant age trend.)

One reason for this distinct pattern is home ownership and wealth accrual over time. Young people are typically more financially stressed because they have had less time to accumulate liquid assets, such as cash and bank deposits.

It’s also possible that younger people are more likely to admit to hardship, though our research suggests this is not a significant factor.

What about JobSeeker recipients?

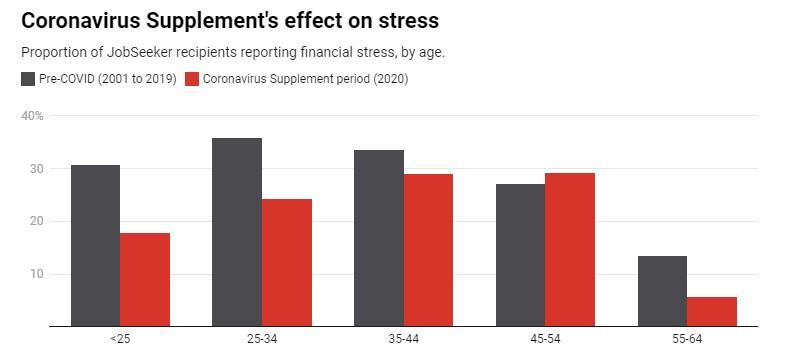

The next graph shows financial stress among JobSeeker recipients by age before and during 2020. It also shows the effect of higher payments in 2020, when the federal government doubled the JobSeeker rate for six months (known as the Coronavirus Supplement).

Thanks to those payments, financial stress among the young fell to its lowest level in at least two decades. But that still meant, on average, those younger than 55 were 2.5 times more likely to report being financially stressed than those 55 and older.

The Coronavirus Supplement experiment in 2020 taught us that a higher JobSeeker payment rate can make a meaningful difference to the financial wellbeing of all Australians, both young and old.

We will find out shortly what the federal government has learned from this policy lesson.![]()

Peter Siminski, Professor of Economics, University of Technology Sydney and Gianni La Cava, Adjunct Fellow in Economics, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.