- Posted on 31 Jan 2025

- 3-minute read

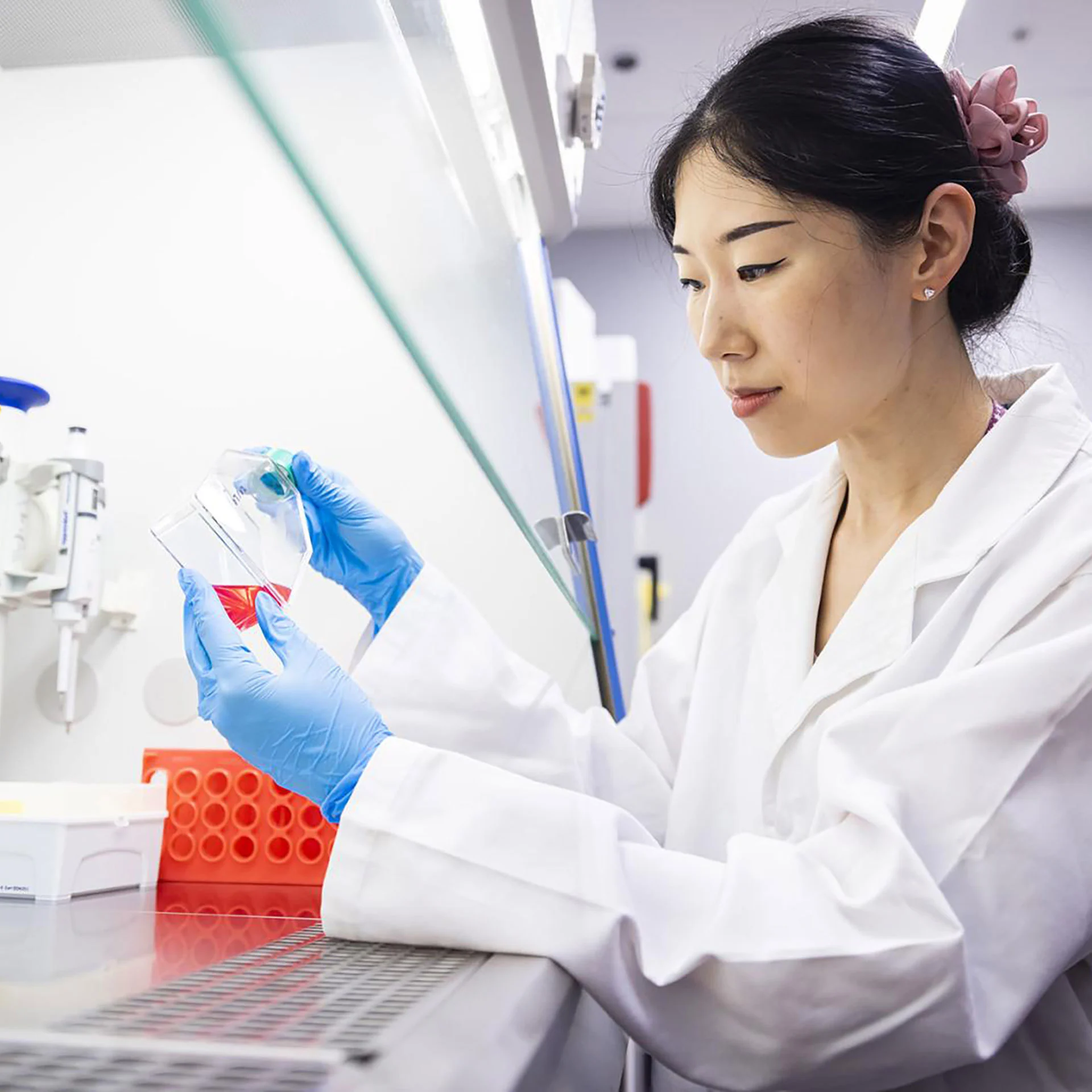

UTS forensic scientist Bridget Thurn recently sampled the scent of ‘Putricia’ the corpse flower.

A corpse flower, aptly named ‘Putricia’, recently bloomed at the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney for the first time in 15 years. For forensic scientist Bridget Thurn, it was a unique opportunity to investigate the intersection of botany and forensic chemistry.

Thurn is completing a PhD in forensic chemistry at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) focused on the chemical profile of human remains, and how this profile changes over time. The aim is to develop technology that can help locate victims of mass disasters.

“I study human remains – specifically the odour of decomposition,” Thurn said. “When I heard the corpse flower, Amorphophallus titanum, was blooming, I thought, ‘Does it really smell like human decomposition? What chemical compounds does it produce?’”

Her curiosity sparked a unique collaboration. Thurn contacted the Botanic Gardens of Sydney and kept a close eye on the livestream, waiting for Putricia to bloom. She had to be quick to collect a sample of the stench because it only lasted for around 36 hours.

Putricia began unfurling around 1pm on Thursday January 23, and Thurn collected samples every two hours from 4pm until midnight, continuing the next day from midday until 10pm. She described the initial scent as “a combination of old laundry, a bakery, and sulphur,” but by day two, it had evolved into “a much more musky and aged smell, more like cheese.”

The corpse flower’s ability to mimic the smell of rotten meat is a fascinating adaptation, evolved to attract insects for pollination. Human decomposition odours are also shaped by complex biological processes.

“I want to see if the compounds from the flower overlap with the ones I’ve identified in my research and, if so, how they compare,” Thurn said. Samples are collected using sorbent tubes connected to small vacuum pumps, which trap volatile compounds for later analysis in the lab.

Each year, UTS researchers conduct a large-scale disaster recovery exercise, together with defence, police and emergency services, at the Australian Facility for Taphonomic Experimental Research (AFTER). This includes carefully controlled decomposition studies using human donors.

“We cover the donors with rubble to mimic disaster conditions and collect odour samples over one to two weeks,” Thurn said. “The results are crucial for refining detection methods. We’re the only group conducting disaster trials like this, so our research is filling a major gap.”

Does it really smell like human decomposition? What chemical compounds does it produce?

Thurn said gasses are released as bacteria break down proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates, with decomposition starting in the pancreas and the gut with digestive enzymes and then spreading. Insects then accelerate this process, releasing volatile compounds as they digest tissue.

This shared chemical landscape makes the comparison between the corpse flower and human decomposition particularly fascinating.

“Some papers have found overlapping compounds between the two, but I’m interested to analyse my database to see what’s really going on. Does the corpse flower’s smell accurately mimic decomposition? Does it live up to its name?” Thurn said.

Thurn’s journey into forensic chemistry was inspired by a childhood fascination with The X-Files. After completing an honours project on how hydrated lime affects decomposition, she decided to extend her research.

Thurn recently published a paper in Forensic Chemistry: Ante- and Post-Mortem Human Volatiles for Disaster Search and Rescue. She is looking forward to advancing the science of malodourous compounds, with her unexpected detour into the world of corpse flowers.