Women’s sport is on the rise, with groundbreaking research now tackling the unique needs of female athletes’ and closing the long-standing gaps that have slowed progress.

Women’s sport is thriving like never before. From the Matildas’ inspiring World Cup run in 2023 to women winning 13 of Australia’s 18 gold medals at the 2024 Paris Olympics, female athletes are taking the spotlight.

This momentum isn’t just about visibility – it’s driving investment, advancing training and creating more opportunities for women and girls in sport.

Yet for years, sports science research has primarily focused on men, overlooking the specific needs of female athletes. Many training methods still rely on outdated models that treat women as smaller versions of men.

Researchers at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) are working to change that. Experts like Dr Katie Slattery, Dr Libby Pickering Rodriguez and Georgia Brown from the School of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation are leading efforts to support women in sport. Their work focuses on understanding the unique needs of female athletes and addressing long-standing gaps in research, helping to drive greater equity in the field.

Featured researchers

The historical gap in research

For much of sports science history, research has focused on male athletes, with training methods and models built around their physiology. In an effort to control the research process, women were often excluded from studies, creating gaps in understanding key areas like training adaptation, biomechanics and recovery specific to female athletes' needs.

Dr Katie Slattery, a UTS lecturer and endurance performance expert, has spent years working with elite organisations like the NSW Institute of Sport and Cycling Australia (now AusCycling). She played a key role in preparing the women’s track endurance cycling squad for the 2016 Rio Olympics.

Now, she teaches future sport and exercise science practitioners at UTS, supervises PhD students and continues research in high-performance sport. Her work includes optimising training loads, testing interventions and recovery strategies to improve physiological adaptation and performance.

Throughout her career, Slattery has seen significant shifts in women’s sport, though progress has been slow. When she began her research journey at UTS in 2003, she was advised against including women in studies because their hormonal cycles were considered “too difficult” to manage.

“In research, you generally want to control everything and change just one factor. But of course, women’s hormones fluctuate every month, and managing the menstrual cycle in studies has often been seen as too complex,” she says.

By 2010, attitudes were shifting, and Slattery was given the green light to include women in her research on heat and hypoxia training for athletes – although there were still far more men in the study than women. She made progress by tracking menstrual cycles and standardising data collection at consistent points in their cycle. It wasn’t a perfect system, but it was a step toward better understanding how women’s bodies respond to training and recovery.

Around the same time, Dr Libby Pickering Rodriguez, a UTS lecturer in biomechanics and researcher, was starting her PhD. While there was growing enthusiasm for studying female athletes, it wasn’t without challenges.

“Working with full-time male athletes at the Sydney Swans was straightforward – they were at the club five or more days a week,” she shares.

“But when I conducted research with the female netball team, the Sydney Swifts in 2013, there were roadblocks.

“Although they were the highest-level netballers in the country, most players were part-time athletes, balancing sport with jobs and family. The coach only had a few sessions with them each week and I had to fit testing around their schedules. It was a lot to ask of them to take on another commitment,” says Pickering Rodriguez.

1896

The year the first modern Olympic Games were held in Athens, Greece and only men were permitted to compete. It was considered by Olympic organisers that the inclusion of women would be “impractical, uninteresting, unaesthetic and incorrect”.

Women in sport | National Library of Australia (NLA)

2012

The year the first Summer Olympics featured female athletes in all events, and all national Olympic committees sent a female athlete to the Games.

In research, you generally want to control everything and change just one factor. But of course, women’s hormones fluctuate every month, and managing the menstrual cycle in studies has often been seen as too complex.

The shift toward female-focused research

There’s been a notable shift towards focusing on female athletes, and that shift is bringing fresh insights into how their bodies respond to training and recovery.

“Understanding the differences between men and women in sport is essential for creating effective training programs,” says Pickering Rodriguez.

“To improve women’s sports, we need to invest in research and evidence-based practices specifically tailored to female athletes, not just increasing financial support.”

Starting her career in more recent times, Georgia Brown, a recent PhD graduate at UTS and Sport Scientist with San Diego Wave Fútbol Club, has focused her research on one of the most overlooked areas in female sport: how the menstrual cycle affects performance and recovery. Previously a Sport Scientist with Australia’s national women’s soccer team, the Matildas, her research integrates findings from both the Matildas and domestic league teams.

“At first, I considered researching fatigue and load monitoring, but as I focused on female athletes, I wanted to study something unique to them. The menstrual cycle stood out – it’s fascinating physiologically and crucial for women and teams to work with,” says Brown.

Slattery has seen first-hand how a lack of research and understanding impacts women’s training programs.

“Coaches in endurance sports have used the same training methods for women as for men, but it doesn’t always work,” she explains.

“Women don’t have the same hormonal response, which plays a role in adaptation and recovery after exercise. This means that women can’t always tolerate the same training loads as men.”

In sports, it’s easy to fall into the trap of comparing men’s and women’s games. But the true value comes from celebrating what makes each one unique.

Take netball, for example. While traditionally a women’s sport, men’s netball is growing – but it’s not just a copy of the women’s game. Men play it differently, much like rugby sevens, where the structural and physiological differences between men and women influence their style of play.

“Women’s sport is different, and that’s what makes it exciting,” says Pickering Rodriguez.

“Body shape is a key factor. Men are typically more straight-up and down, while women have hips, which affects landing, movement and direction changes,” she explains.

There are also differences in muscle fibres, body composition and the ratio of muscle mass to fat mass.

“Rather than mirroring men’s styles, female athletes are embracing their differences and playing the game in their own way – and that’s something we should all champion,” Pickering Rodriguez says.

Improving women's performance through science

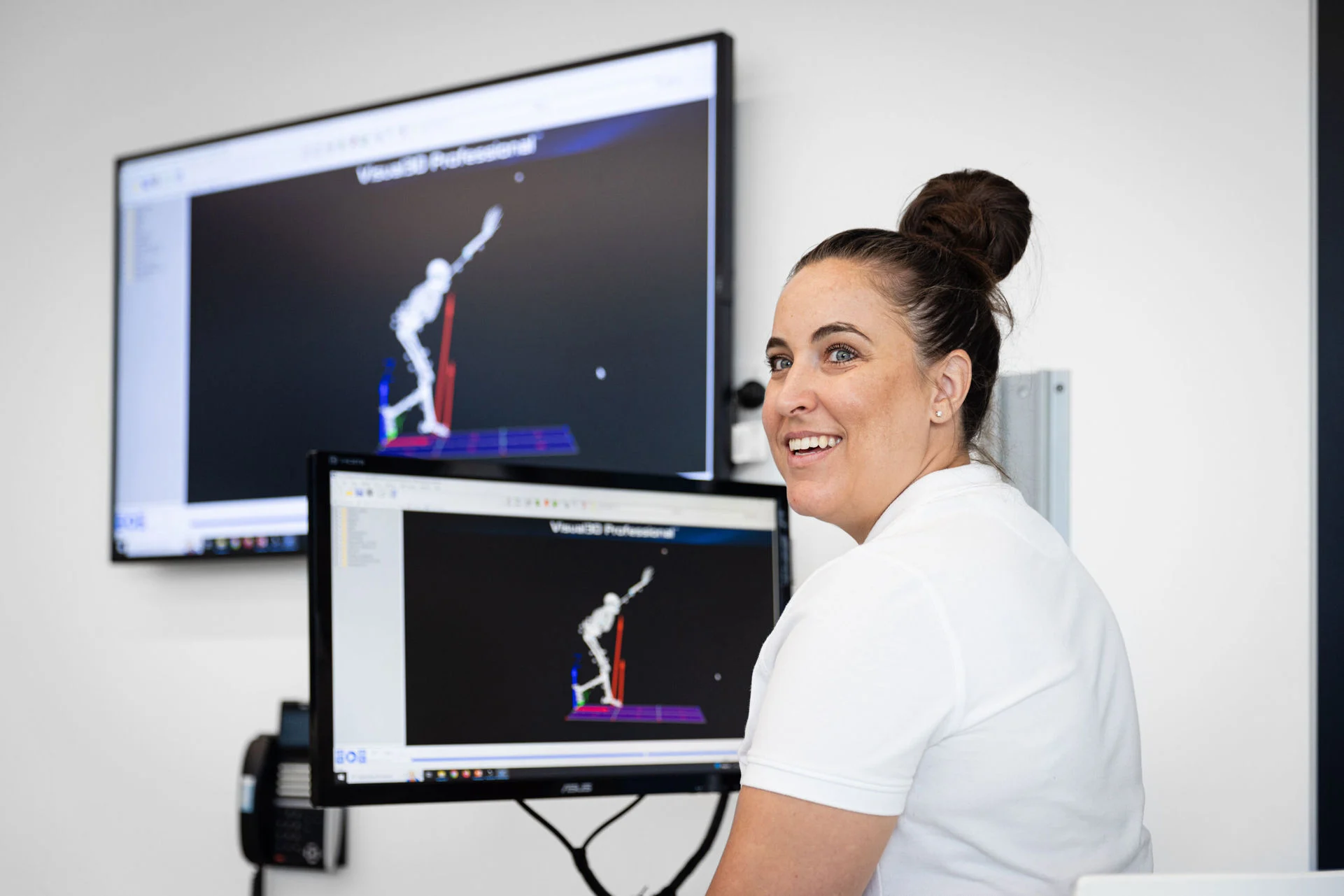

Pickering Rodriguez is leading Project 130, a partnership with Cricket NSW aimed at improving female fast bowling. The project also has a long-term goal of increasing the average speeds of female fast bowlers from 115 km/h to 130 km/h.

At the biomechanics lab in Moore Park, bowlers run and bowl on a 40-metre indoor pitch wearing motion-capture markers, while 20 motion capture cameras and six force plates track their movements. This data creates 3D models that analyse joint angles, movement patterns and ground reaction forces. The team also collects information on height, arm length, speed, strength and power to identify key performance drivers.

The research, which involves both elite and emerging female fast bowlers, not only aims to understand what drives performance, but also helps uncover new talent by pinpointing physical and technical traits linked to fast bowling success.

“There’s no significant data on female bowlers, so we’re building from scratch,” says Pickering Rodriguez.

“So far, we’ve found that female fast bowlers use different strategies to reach high speeds than men. For example, fast bowling relies on leverage, which means longer arms and legs typically provide an advantage. Since men and women typically differ in their anthropometry, their bowling mechanics naturally vary.”

Pickering Rodriguez’s research is still in the exploratory phase.

“Right now, we want to increase our sample size and then do more confirmatory research to see if we find common factors among athletes who bowl faster. If we do, we could then move into training interventions to modify those factors.”

109 kph

The fastest ball bowled by a female athlete in the UTS indoor biomechanics lab.

Understanding the menstrual cycle for performance

Meanwhile, Brown’s research on menstrual cycles is providing essential insights into how hormonal fluctuations affect performance.

Brown began by conducting a menstrual health screening of national and domestic league players to identify common conditions and perceptions. Next, she tracked the menstrual cycles of domestic league soccer players over three cycles, focusing on two key factors influencing performance: hormonal phases and symptoms.

Using GPS data, Brown tracked match performance and monitored players’ perceived fatigue, soreness, stress and recovery. She explored how different phases of the menstrual cycle affected running, speed and recovery. Brown found that players ran more during the late follicular phase (mid cycle) than during menstruation or the luteal phase (end of cycle). However, the effects varied among athletes, highlighting the importance of individual approaches.

“Some athletes aren’t affected by their cycle, while others are. For those who are, we can adjust factors like hydration, nutrition, sleep and training loads,” she says.

While there's no strong evidence yet for blanket recommendations about training or nutrition based on cycle phases, Brown believes individual management is key.

“It’s about monitoring for patterns and adjusting based on what affects the individual athlete.”

Brown has also helped develop a menstrual health screening tool used by the Matildas. The tool helps track athletes’ menstrual health and symptoms, monitors hormonal contraceptive use and assesses the perceived effects of the menstrual cycle on performance.

“We have made the menstrual health screening tool available with the published research so that all clubs, teams and researchers can access and use it,” she says.

For Brown, the tool is not just about collecting data – it’s about creating actionable plans and encouraging conversations around menstrual health. It gives athletes the opportunity to voice concerns about their symptoms, even minor ones, ensuring that they feel supported and heard.

The percentage of players in Brown’s research who perceived their menstrual cycle as disruptive to their performance.

Building momentum

Thanks to crucial research and increased investment, women’s sport has been gaining significant momentum in recent years, with growing fan support and rising viewership.

In women’s cricket, Pickering Rodriguez believes fast bowling could elevate the game: “Bowling as fast as you can, ripping out middle stump or making the batter swing and miss – that’s one of cricket’s greatest spectacles.”

“If we can reach a greater level, it will take women’s cricket to new heights, attracting more viewership, sponsorship and recognition,” she says.

In football, the Matildas’ success at the 2023 Women’s World Cup has sparked a ripple effect, boosting interest and investment in women’s sports worldwide.

The event also saw a shift in fan engagement: “We went from giving away free tickets to games to people fighting to get tickets to the Women’s World Cup,” says Slattery.

Brown notes that their success has also inspired more women and girls to get involved in the game at grassroots, with a 16% increase in participation in 2024. What was once an insult – “You play like a girl” – is now a badge of honour. Young athletes look up to role models like Mary Fowler and Mackenzie Arnold, who show that women can build successful, professional careers in sport.

Slattery highlights how far things have come: “Women are no longer just participants; they’re building careers and receiving the financial support needed to train, play and compete.”

"In the past, top female cyclists had to support themselves to race. Often, they funded their own trips to Europe and competed for a much smaller prize pool than the males. Today, female cyclists can have lucrative careers," she says.

Changing policies around maternity leave are also making a difference.

"Women have babies, and their careers often last into their 30s and 40s. I’ve heard stories of women being the first in a professional team to have a baby – and sometimes, they never come back. Now, maternity leave policies are essential, and we are seeing many more 'mum-athletes' balancing being a parent with professional sport,” she shares.

million pledged for Play Our Way by the Australian government during the 2023 Women’s World Cup – its biggest investment in women’s sports.

million in prize money for the 2023 Women’s World Cup. Men were awarded $440 million in prize money during the 2022 World Cup in Qatar.

Still some way to go

While women’s sport has made great strides, there’s more to be done. As Pickering Rodriguez says, “We’re slowly chipping away at the barriers.”

Many elite female athletes in sports like rugby sevens, AFL and cricket often start later than their male counterparts, having fewer opportunities to develop their technical and tactical skills from a young age.

“Many women enter these sports having transitioned from other disciplines. They’re exceptionally talented, but they’re still mastering new skills,” she says.

“If people understood that better, they’d be in awe of what these women are accomplishing.”

Brown sees the same trend in soccer: “Boys enter football academies by age 12, while girls often don’t start until later.”

She highlights the need for greater investment at every level, from grassroots initiatives that provide female-specific kits to ensuring girls have access to proper training facilities and change rooms.

Even at the elite level, female teams often train on subpar pitches and lack key resources. For true equity in sport, this must change.

One of the most pressing challenges is the high dropout rate among young female athletes during their teenage years.

Slattery notes that girls aged 12 to 17 often miss out on the same training opportunities as boys, especially in strength and conditioning. While more research is needed, this disparity is believed to contribute to both dropout rates and injuries, such as the higher incidence of ACL injuries in female athletes.

Misconceptions around strength training also persist, such as the myth that “lifting too much will make you bulky.” Addressing these myths and barriers is crucial for further progress to be made.

Investing in women

Some sports like triathlon have led the way in gender equality, offering equal pay, competition length and prize money for men and women. A key shift is also recognising the importance of women’s representation in all areas of sport.

“Representation in the media matters. When young girls see women in various roles – whether as athletes, coaches, commentators or sports scientists – it shows them what’s possible,” says Brown.

But representation alone isn’t enough – real change comes from ongoing investment and support.

For these three researchers, their work goes beyond simply gathering data. As Pickering Rodriguez shares: “It’s about giving women the visibility they deserve.”

“It’s about showing them that we see them, we value them, and we’re investing in them.”

And that investment is already making a difference for the athletes involved in the research.

“Many young girls attend the research program with their parents, eager to be part of the experience,” Pickering Rodriguez says.

“I’ve also heard older players take part and say, ‘I know this won’t help me, but I want to invest in the next generation.’”

This kind of support reflects the immense potential for the future of women’s sport. By continuing to invest, sporting organisations, government bodies, media outlets, researchers and fans are not only supporting today’s success but also laying the foundation for future generations of women to rise, achieve and break new boundaries.