Imagine a future where damaged hearts can be repaired, rather than replaced. Researchers at UTS are developing patches using human stem cells that could see a cheaper, safer and longer-lasting solution for people living with heart disease.

Our hearts work tirelessly to sustain us throughout our lives, delivering oxygen and nutrients to vital organs.

“It’s always moving,” says Professor Andrew Coats, Scientific Director and CEO of the Heart Research Institute (HRI).

“Every person alive today is at risk of dying within 10 seconds if that mechanism doesn’t work.”

Cardiovascular disease, which includes conditions like heart failure and strokes, is the leading cause of death globally. In Australia, it claims a life every 12 minutes.

Featured researchers

Heart problems

Heart transplants are the go-to solution when the heart fails to pump blood effectively, but they come with a host of challenges.

There aren’t enough donor hearts to meet demand, meaning patients face long wait times – sometimes stretching into months or even years.

Transplants can also be prohibitively expensive. In Australia, a heart transplant alone can cost more than $140,000, never mind the ongoing costs of medicine and other maintenance activities. It involves a major surgery and isn’t always a long-term fix.

"We have over 10,000 new patients diagnosed with heart failure every year in Australia, and 50% of them will die within a few years after transplantation,” says Professor Coats.

of all deaths in Australia are from cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Inspired by life

Dr Carmine Gentile, Senior Lecturer at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) within the School of Biomedical Engineering and Cardiovascular Regeneration Group Leader, witnessed the debilitating effects of cardiovascular disease firsthand through his father's struggles.

"There has been a history in my family around cardiovascular disease starting with my dad. And that prompted me to investigate further,” he says.

Gentile wanted to discover better ways to help heart failure patients and overcome one of the field’s biggest obstacles – translating these discoveries into the clinic.

He moved from Italy to the United States to work on his PhD in Biomedical Sciences, focusing on cardiovascular bioengineering.

“During my American PhD I was exposed to really novel technologies which include 3D bioprinting of tissues and organs,” he says. “Nowadays this technology is familiar to the general public thanks to the extensive media attention, but back then when I started my studies in 2006 it was a completely novel technology.”

As part of his PhD studies, he was invited to one of the world’s pioneering laboratories in the US dedicated to this research, and in 2016, he introduced the first bioprinter to Australia for his work with the HRI.

I took on a journey in pharmaceutical chemistry and what was obvious to me is that major research done in the lab was failing to translate from the bench to the bedside.

It takes a (multidisciplinary) team

Now Gentile’s based at UTS, where he’s established the Advanced Biofabrication Facility, which is equipped with 9 bioprinters and all the other equipment to test the safety and efficacy of bioprinted heart tissues. Gentile’s multidisciplinary team includes experts from industry and academia, as well as several PhD, postgraduate and undergraduate students.

“I like to motivate my students by telling them that they will become the master chefs of science,” he says. “To succeed in science, you must be creative, so that your ideas can pave the way we study a disease and potentially impact patients.”

Each member of Gentile’s team focuses on a different aspect of the research: stem cells, biomaterials, 3D modelling, medicine, pharmacology, design, engineering and arts.

The team even includes two artists, whose life-size model of the heart helped Gentile “realise we were doing everything wrong” after the team had been working with virtual models during COVID lockdowns.

The research team’s work is done in partnership with the Heart Research Institute, whose clinical team guides them on how to progress their research from the lab to their goal of helping patients.

What’s the solution?

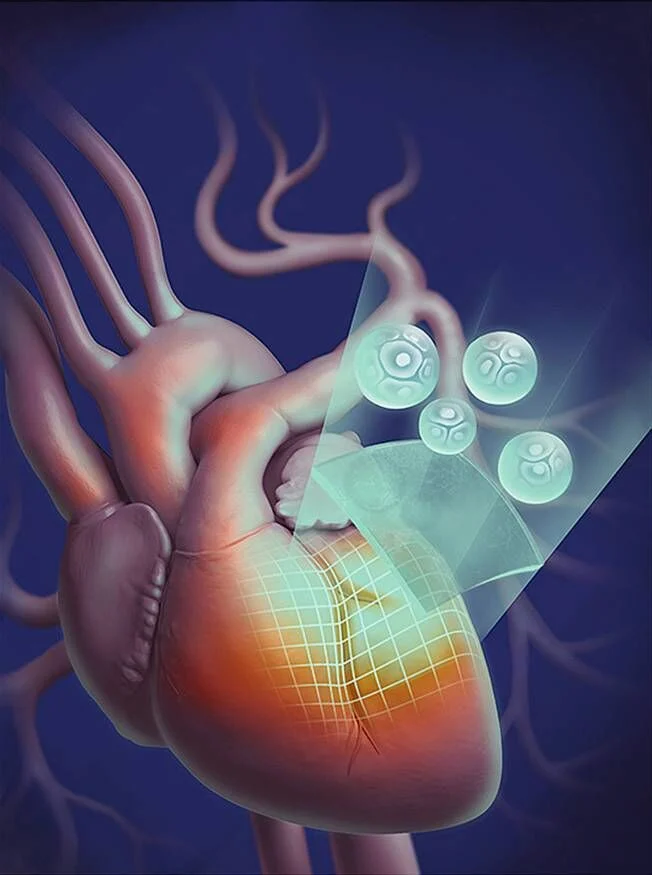

Gentile and his team are working on creating bioprinted heart patches to help the heart heal and function better. Their work uses 3D-printing techniques to create complex structures such as living tissues using materials that are safe for implantation within the body.

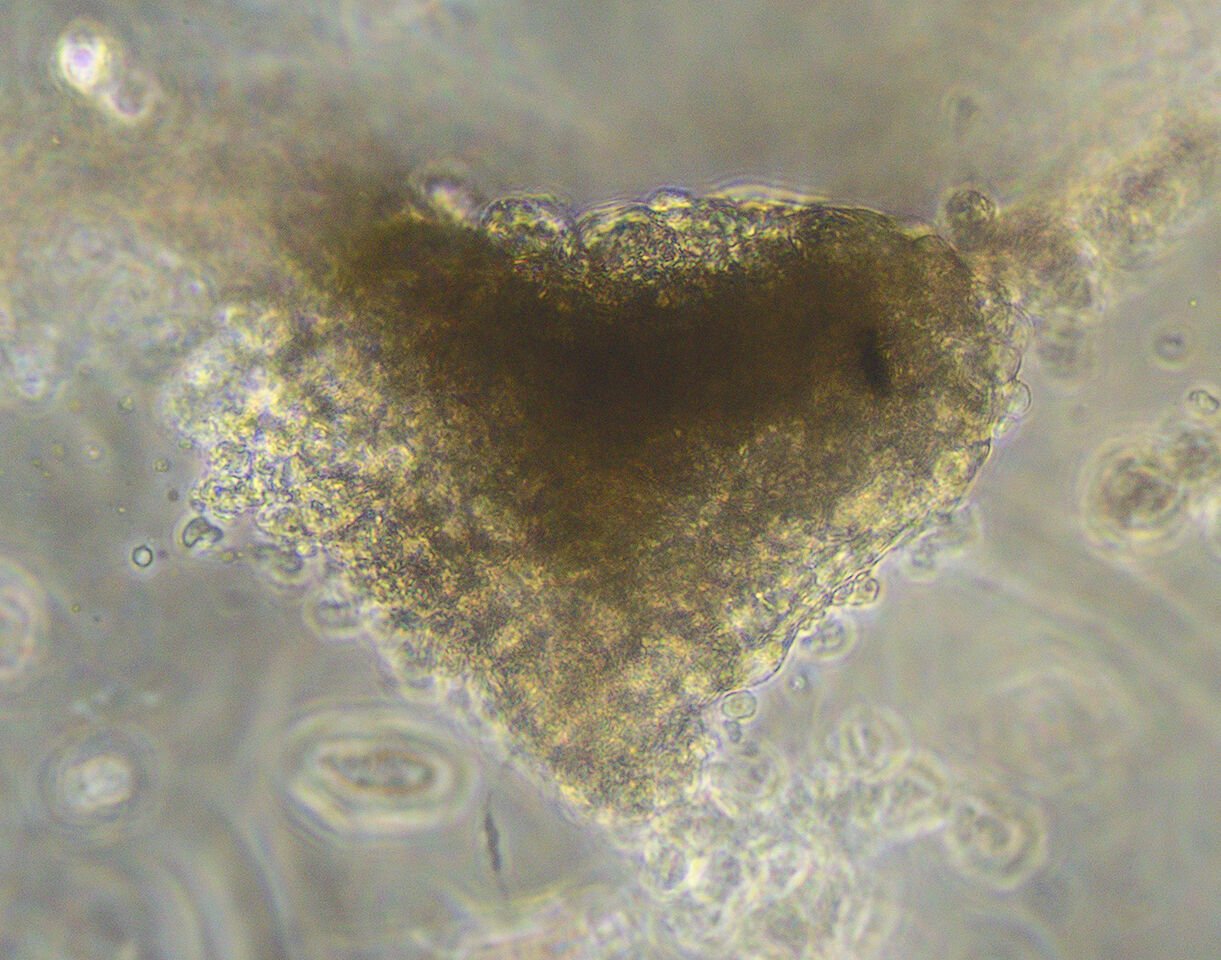

They have developed a special type of ink for patient-specific 3D-printed patches, called bio-ink. It’s a sophisticated mixture of biological materials including hydrogel and miniature hearts made from the patient’s own stem cells.

Stem cells, with their remarkable ability to turn into different cell types, hold immense potential for regenerative medicine.

“I like to think of it like LEGO,” says Niina Matthews, a PhD candidate working in the UTS research team.

“We take different cell types and get them to connect just right like in a human body. Cells become tissue and from different tissue types together come an organ.”

A quick recovery

One of the best aspects of the heart patch is its minimal invasiveness.

Through his position at HRI, Gentile has witnessed the impact traditional open-heart surgery has on patients first-hand.

“What patients highlighted was their pain associated with the procedure,” he says. “They might have to repeat an open-heart surgery every 10 years. A patient in her 40s explained to me she had her first procedure at 3 days of age. She always remembers the pain.”

Instead of performing major surgery, doctors could fold and transplant the heart patches through a small incision using robotic arms. This means less trauma and a quicker recovery for patients.

My hope is to have the patient walking in and out of the clinic in the same day.

Reaching all patients

The research team is committed to improving the technology to make sure it works well over time and is ready for use in clinical trials.

“We want to create a solution that is not only applicable to Australians, but that could benefit any heart failure patient globally,” says Gentile.

While preclinical trials have shown promise, one challenge in making the treatment universally available to patients is obtaining regulatory approval.

Researchers are in ongoing conversations with regulators to ensure bio-solutions like heart patches can be standardised and considered safe as soon as possible.

As well as being highly effective and personalised, the research team’s goal is to create a solution that is affordable and widely available to those in need. The development of automated bioprinting systems for clinical use could make that possible.

The beat goes on

From bringing the first bioprinter to Australia, Gentile is now working in what he considers to be the best bioprinting and testing facility. Here, his team can create stem cells from patients and bioprint and test mini hearts and patches.

These patches offer a promising solution for heart failure by repairing damaged hearts. As research continues, the potential of this technology grows, representing a major step forward in cardiac care and offering new hope for many.

In the meantime, the team are researching other ways mini hearts can be used to improve patient outcomes. This includes testing the effects of cancer therapies on cardiovascular patients, and more recently, creating “heart attacks in a petri dish”. Notably, the team has discovered that microalgae can protect from a heart attack by using mini-hearts in their lab. The results so far are looking promising.

Heart patches

Bio-printed heart patches offer a minimally-invasive alternative to surgery.