Think of all the times you use water throughout the day for washing, cooking, drinking, cleaning. Much of our day is made possible thanks to the privilege of being able to turn on a tap and have clean water come out.

For a city like Sydney, it takes a massive network of pipes and supporting infrastructure to transport clean water to our taps and carry wastewater away to be treated. Utilities work hard to ensure consistent delivery of water, but it’s a constant battle to prevent leaks and asset failures, with little room for error.

The sheer size of the network means it’s hard to manually inspect everything on a frequent basis. This is compounded by the fact that water infrastructure is ageing, and Sydney’s growing population will only continue to put stress on the network as demand continues to climb.

With traditional maintenance methods expensive and time consuming, Sydney Water partnered with researchers at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) to see if there’s a better way to maintain the system responsible for delivering this vital resource to homes and businesses.

The result is a perfect demonstration of how combining robotics, artificial intelligence, data science and the Internet of Things not only makes it easier to react more quickly to leaks and failures – but that it’s possible to predict faults before they happen.

Out of sight, but top of mind

Much of the city’s water infrastructure is below ground, making everything from routine inspections to critical infrastructure replacements costly and time consuming. On average, water utility operators can inspect just 1% of network assets each year.

Beyond the costs of materials and maintenance, burst or leaky pipes have hidden costs. Service disruptions affect the public’s quality of life, and leaks mean more energy needs to be expended to maintain water pressure.

And then there’s the environmental impact: Australia is the world’s driest inhabited continent, so there’s not a drop of water we can afford to lose through cracked or burst pipes.

“It’s a complex system with so many different angles to think about,” says Distinguished Professor Fang Chen, Executive Director of the Data Science Institute at UTS.

The average age, in years, of a Sydney water pipe

What a water utility can spend annually on maintenance activities

Reactive maintenance is 10 times more costly than proactive maintenance, making proactive maintenance the smart choice both environmentally and economically.

Mining the waters

Chen has built her career on finding practical applications for data science and artificial intelligence. Her resume includes time with companies such as Intel and Motorola. Most recently, she worked with the CSIRO’s Data61, where she earned a Eureka Prize in 2018 for her use of data science and analytics tools to predict water infrastructure failures.

Suffice to say, there’s no one better placed to tackle the challenge of applying cutting-edge data science and machine learning to predictive infrastructure maintenance.

“I’m always centred around using data and understanding what are the insights, patterns and behaviours behind the data, and then what can we do about it,” she says.

UTS and Sydney Water have partnered together on various projects since 2013. Once Chen joined UTS in late 2018, the pieces fell into place to further study opportunities to use data science and predictive analytics for water network maintenance.

From there, they used AI and machine learning algorithms to conduct a risk analysis to identify areas of the network that were most prone to failures, as well as identify common themes as to why and how pipes failed.

Interrogating this data yielded more than 20 predictive factors drawn from four buckets of information:

- attributes of pipes such as when they were laid and material composition

- surrounding environment (for example, geological factors such as soil type)

- operational parameters such as pressure and chemical usage, and

- records showing what has happened in the past and why.

These factors helped the team narrow the search field to pipes that fit the criteria for most at-risk of developing a leak or otherwise failing.

Good vibrations

Once the research team identified the most high-risk pipes and locations, Chen says it was important to gather even more data to home in on why, when and how particular areas of the network experience failure.

“It’s like when you’re sick and go to the doctor, they take your medical history and provide an initial diagnosis,” she says.

“But then depending on the symptoms that appear, that’s when they send you to get blood tests, or get X-rays.”

In order to build a more robust predictive model, Chen says the team needed to gather real-time data through precise monitoring of at-risk pipes, which would allow them to continuously feed information into their prediction algorithms to better train it.

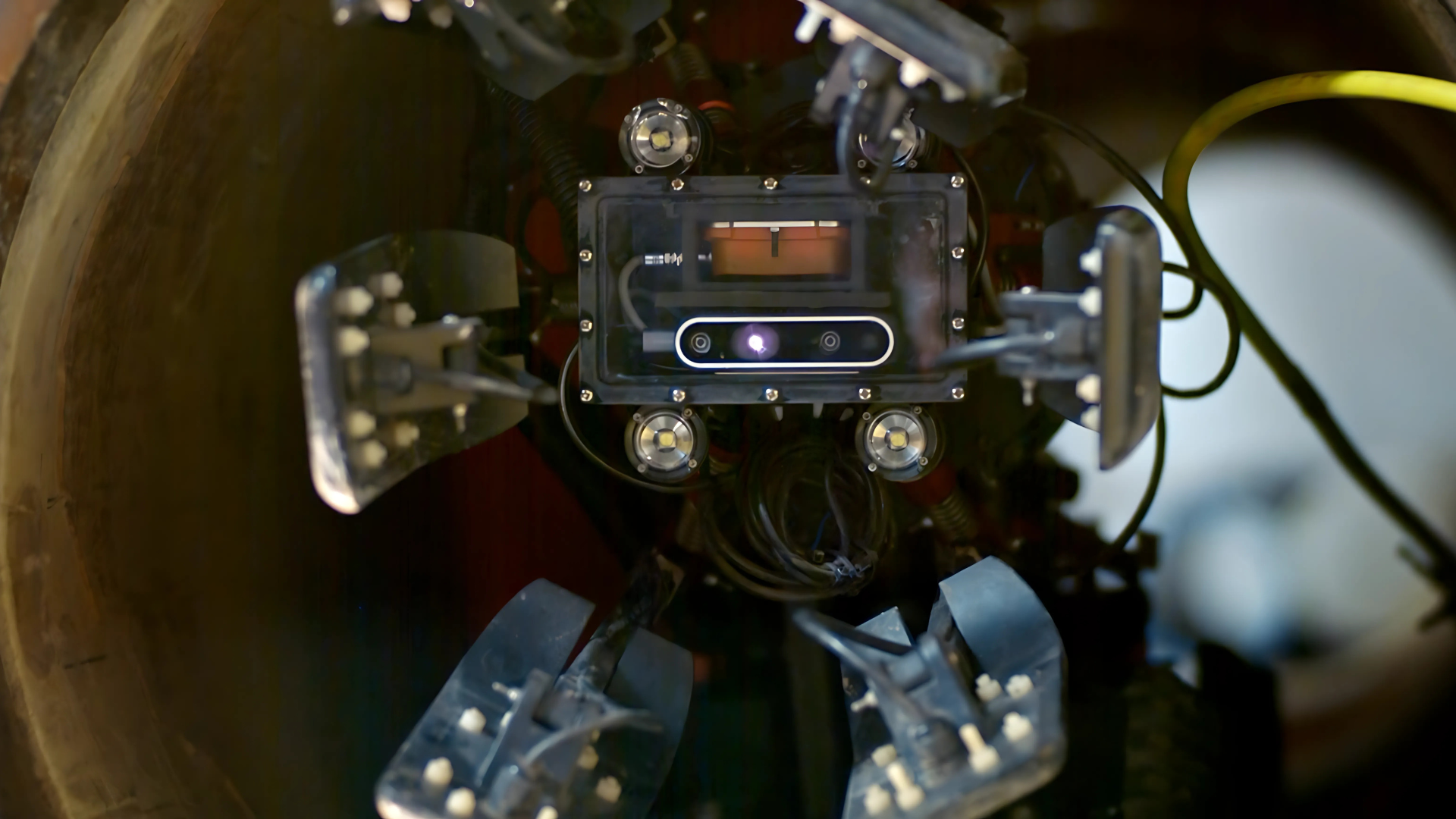

Believe it or not, one of the best ways to detect water leaks is actually to listen for them. Sydney Water and UTS worked together to place acoustic sensors around parts of the network using purpose-built robots developed by the UTS Robotics Institute. These sensors, also developed by roboticists at UTS, are finely tuned to pick up the subtle vibrations produced by a leaky pipe

One challenge was to find the right locations to deploy the sensors for maximum resolution and efficiency.

“Some water pipes might be 4km long, so determining exactly where to place the sensors and how many to place was crucial,” Chen says.

Once deployed, the sensors helped Chen and the rest of the team fine-tune their data analytics models to better forecast failures. One big achievement of this research, she says, was establishing a strong methodology for gathering data and improving the quality and accuracy of the data captured.

The result is a world-first pipe failure prediction tool designed to better understand where and when pipe failures occur.

number of data records analysed as part of this research project

Future flow

UTS and Sydney Water tested the prediction tool extensively before deploying it fully. It’s now part of business as usual for the utility, which is already seeing savings. In the first year of deployment, the utility saved nearly $30 million. The team at UTS also continues to work with water utilities to further develop the predictive maintenance tool – it’s consulted with more than 30 globally.

Chen estimates that their system is four to five times better at predicting pipe failures than previous methods. She says applying this research to networks for cities around the world could cut maintenance costs by as much as half. Imagine such a system applied in large metropolises with ageing infrastructure like New York City or London. The potential for savings in time, money and water is huge.

gigalitres of water Sydney Water saved over the course of a two-year trial, enough to fill 4000 Olympic-sized swimming pools

Bringing in data scientists and technology experts to work with utilities to better understand the cause of faults and how to prevent them in the future represents a larger shift in the infrastructure industry away from reactive repairs to proactive maintenance.

“There is a fundamental change happening in the mindset of the industry on how to maintain assets, because most assets have been maintained in a reactive way,” Chen says.

“Using predictive analytics to do preventative maintenance and having that become business as usual is a huge achievement. I think there is huge potential to grow from here.”