Viking Invasion!

Michael Olsson, who is involved in a research project exploring approaches to the documentation of historical artefacts from their unearthing in archaeological digs to their inclusion in museum exhibitions, has visited the Viking exhibition currently on display at Sydney’s National Maritime Museum. He writes here about how we are involved in the creation and re-creation of understandings of the Vikings as cultural icons. He says:

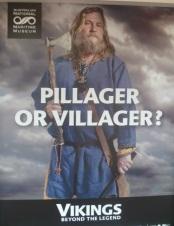

“We are in the midst of a Viking invasion. Sydney’s National Maritime Museum is currently hosting a special exhibition Vikings Beyond the Legend, while the Danish National Museum’s 2013Viking exhibition will be the star turn of 2014 at the British Museum. At the same time, a new historical drama The Vikings is on our TV screens, while no sooner has Thor left our cinemas thanThe Hobbit full of dwarves, dragons, treasure hordes and riddle games derived from Norse myth starts breaking box office records. And let us not forget the enduring success of Hagar the Horrible…

Where does this fascination come from? What is the appeal of these ancient seafaring peoples of contemporary audiences? It is certainly worth noting in this regard, that interest in Vikings, both in the academy and in popular culture, is a rather more recent phenomenon than we might reasonably assume. While the people we now call Vikings had a dramatic impact on European history from the 8th to the 11th centuries, they were then largely forgotten until the latter part of the 19th, even in Scandinavia. The medieval and early modern kingdoms of Sweden and Denmark wished to be seen as civilised, Christian nations and regarded their pagan forebears as an embarrassment best forgotten.

A variety of factors caused this to change in the late 19th century: Romanticism led to a widespread intellectual and artistic interest in the middle ages. Richard Wagner co-opted many Viking elements for his Ring cycle – and in doing so promulgated the now near universal misconception that Vikings wore horned helmets! 19th century scholars began to rediscover and appreciate the Icelandic sagas, and perhaps most importantly, the newly emergent discipline of archaeology began to uncover Viking era artefacts and treasures, such as the Gokstad longship, which caught the public imagination. This was also a period of rising nationalism, and this also played a role. Denmark and Sweden were both in decline politically and territorially, while a newly-independent Norway was seeking to construct its identity. In this milieu, the notion of a Viking Golden Age of exploration and conquest became popular. In America, the discovery of the possibly spurious Kensington Runestone in Minnesota led to an enormous increase in public interest in the Viking exploration of North America, as chronicled in the Icelandic sagas. Viking imagery was used by both sides in World War Two: for the Nazis, they were an ideal symbol of the Aryan superman; while the Allies sought to use them as an emblem of resistance to the German occupation.

I would suggest that these multiple ways of viewing the Vikings is actually a key feature of their appeal: they allow us to see that these ancient people lived in a society as complex as our own. When one hears that a Viking traveller carved the runes for ‘Halfdan was here’ in a railing in Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, they can seem very close to us. At the same time, while we can admire the extraordinary beauty of Viking carvings and jewellery, much of its symbolic meaning remains opaque to even the experts. Thus the Viking world seems to us both strangely appealing and elusively mysterious – and isn’t that the perfect combination to keep us fascinated?”