Just how ‘naïve’ and ‘fuzzy’ is the Albanese government's approach to China?

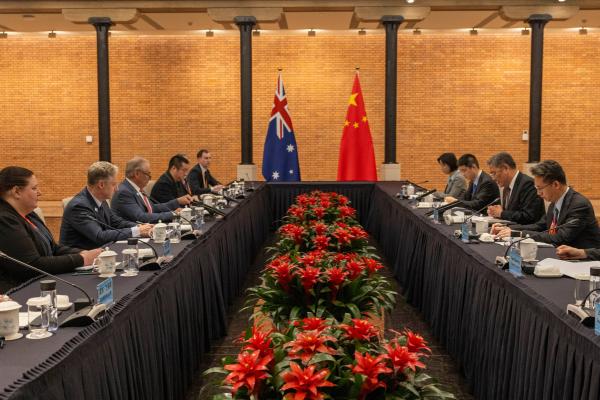

Daniel Walding / DFAT

James Laurenceson, Director, Australia-China Relations Institute, University of Technology Sydney |

This article appeared in Australian Outlook on November 12 2024.

Critics of the Albanese government’s approach to managing relations with China, and in particular its emphasis on ‘stabilisation,’ contend it reflects a ‘dangerous element of naïve and fuzzy thinking.’ Xi Jinping’s China is hostile towards Western liberal democracies like Australia. An ‘unprecedented battle…for influence, for ideas and narratives, and fundamentally for power’ is at hand.

What Canberra should be doing is decisively backing a ‘regionally dominant US‘ and shrinking the attack surface available to Beijing more generally, such as by cutting the exposure of the Australian economy to the Chinese market and suppliers. Instead, Canberra is cowered, saying the ‘barest minimum necessary‘ on deep points of difference in a vain attempt at maintaining ‘stability’ and keeping the dollars from selling wine and beef flowing.

But the critics are presenting a cartoon version of the government’s approach. Its architect, Foreign Minister Penny Wong, does not reside in geopolitical La-La Land.

Wong is a card-carrying ‘realist about China.’ Last April, she took to the National Press Club to emphasise that Australia needed to ‘start with the reality that China is going to keep being China.’ This meant understanding and accepting that ‘China uses every tool at its disposal to maximise its own resilience and influence.’

Where Wong departs from the critics is mostly not around assessments or policy responses, but in the brand of diplomacy she exercises. Wong argues that, ‘we need not waste energy with shock or outrage at China seeking to maximise its advantage.’ Instead, we need to ‘channel our energy in pressing for our own advantage.’

The fact is that the government has not reversed a single substantive policy position of the previous Malcolm Turnbull and Scott Morrison Coalition governments related to the challenges that China presents. Think foreign interference laws, the Huawei 5G ban, AUKUS, and more.

Shadow Foreign Minister Simon Birmingham acknowledged and endorsed this policy continuity in an event at the Australia-China Relations Institute in October. And in other areas, such as contesting China’s influence in Pacific Island countries, the government has been far more active.

What has been abandoned is the Morrison’s government’s abrasive diplomacy and an internal Coalition free-for-all where any minister or backbencher felt at liberty to poke Beijing in the eye. But it is simply untrue to claim that this equates to the government having been scared into ‘public silence.’

There is little more public than a media release. Yet since becoming foreign minister, Penny Wong has issued 32 media releases critical of Beijing, a rate of more than one per month. The topics covered range from Australians detained in China, human rights abuses inflicted on China’s ethnic minorities, and instances where Beijing has trampled international law.

There was even one in June drawing attention to the 35th anniversary of Tiananmen Square crackdown and the Chinese government’s ‘use of brutal force against student protestors.’ In calling on Beijing to ‘cease suppression of freedoms of expression, assembly, media and civil society,’ it was more expansive than the media release issued by then-Foreign Minister Marise Payne in 2019 to mark the 30th anniversary.

Apparently also missed by the critics is that the Morrison government’s abrasive diplomacy has also been abandoned by the Coalition in opposition. Simon Birmingham also said last month that while a Dutton-led Coalition government would not shy away from being ‘clear, firm, [and] consistent’ with Beijing, it recognised that ‘rhetoric and tone’ were integral to ‘good diplomacy.’ And in handling the China relationship, the Coalition would aim for ‘coordination and consistency’ and ‘apply as much unity as possible.’

In railing against Australia’s economic exposure to China, what most critics reveal is the limits of their own understanding. To cite Beijing’s recent attempt at economic coercion as conclusive evidence that Canberra must drive trade away from China is to miss the most basic lessons learned.

What the episode confirmed was Beijing’s unwillingness to disrupt many big-ticket items, like iron ore, LNG, lithium, and wool. This is because China needs Australia as a supplier as much as Australia needs China as a market.

And most of the industries hit were readily able to mitigate the costs. Goods such as coal and barley are traded in open and competitive global markets. When access to China was blocked, these markets quickly redirected Australian supply elsewhere.

The fact that a couple hard-hit industries, like wine and lobster, have rushed back to China when restrictions were removed does not reflect geopolitical naivety. How could wine-makers ‘diversify’ away from China when demand from Australia’s second and third largest markets, the US and the UK, has been falling since 2020? How could Australia’s rock lobster exporters ‘diversify’ their sales when China accounts for 90 percent of global imports?

At the same time, the limits of notions like geopolitical friends banding together to form an ‘economic alliance’ to deter Chinese trade coercion or retaliate against it are now plain to see. It was US companies that snapped up more disrupted Australian sales to China than any other country.

Another case in point: last year, China bought 98 percent of Australia’s exports of lightly processed lithium, worth US$13.1billion. In contrast, the US bought just US$12.4 million.

In part this reflects the US being a laggard in the net zero transition, at least compared with China. But also that the US has significant domestic lithium stocks, and instead of relying on Australian supply to meet future demand the Biden administration has been busy subsidising the opening of local mines.

Similarly, the US is a competitor to Australia in global markets for rare earths and is subsiding the onshoring, not ‘friendshoring,’ of processing facilities. Much of Australia’s critical minerals production is ineligible for subsidies contained in US industrial policy initiatives like the Inflation Reduction Act.

Another initiative out of Washington to attract some local excitement was an amendment to the US Defence Production Act that listed Australia as a ‘domestic source.’ But the fine print clarified that Australia will only be considered a ‘domestic source’ if US demand ‘cannot be fully addressed‘ by companies in North America.

There is much ‘naïve and fuzzy thinking’ about how Australia should manage relations with China. Fortunately, for the time being at least, most of it is coming from outside of government and so with limited access to the levers of power.

Author

Professor James Laurenceson is Director of the Australia-China Relations Institute at the University of Technology Sydney.