The biggest threat at the beach this summer? It’s not sharks

With summer on the way, you might be thinking about your first swim of the season — and perhaps about what lurks beneath the water at your favourite beach.

But if you’ve got sharks on your mind, UTS Professor Justin Seymour has some news for you: the biggest threat isn’t your life descending into a real-world rendition of Jaws. It’s something much smaller, much more abundant and invisible to the naked eye: microbes.

“Every millilitre of seawater has about a million bacteria and 10 million viruses in it,” says Professor Seymour, who leads the Ocean Microbiology Group in the UTS Climate Change Cluster (C3) research centre.

You can imagine if you expand that across the entire volume of the ocean, we’re talking about really massive numbers of these microbes.

Professor Seymour and his team are interested in all of those microbes — the good guys (most of them), the bad guys (some of them), and the truly gnarly pathogens (a small but significant group) that make millions of beachgoers sick every year.

Common illnesses include gastrointestinal upsets, skin and eye infections, and food poisoning from contaminated seafood, all of which occur in astronomically greater numbers than the ~70 unprovoked shark attacks recorded annually across the globe.

These pathogens come from a range of different sources. Some are endemic to the marine environment, while others are introduced to the ocean via stormwater and sewage runoff. But what the Ocean Microbiology Group is most fascinated — and alarmed — by is that warming ocean waters are driving a boom in these microbial hazards.

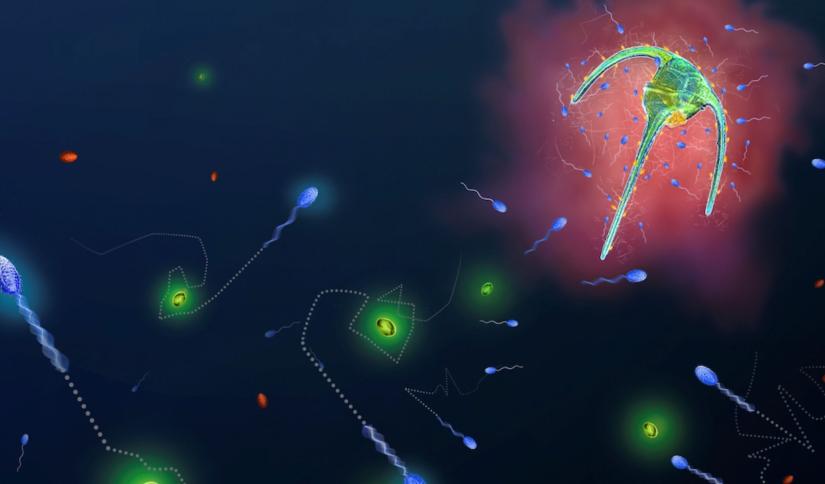

marine microbes

“Many aquatic pathogens prefer warm water, and there is already evidence that climate change is increasing their threat to human health,” Professor Seymour says.

The solution — or at least the opportunity to mitigate these impacts — lies in part in microbiology research. Professor Seymour and his team are leading a suite of projects to better understand and measure water contamination and marine bacteria. As well as shaping the contemporary scientific landscape, this work also informs the UTS Science curriculum and creates exciting opportunities for higher degrees by research.

The Ocean Microbiology Group’ research includes exploring the increasing risk of antibiotic resistance among marine microbe communities and its impact on the health of beachgoers, developing more precise approaches for detecting and tracking dangerous aquatic pathogens, and using DNA sequencing technologies to identify sources of contamination and improve water quality.

Recently, as part of a collaboration with Central Coast Council and the NSW Department of Climate Change, Energy, Environment and Water, the Ocean Microbiology Group identified a stretch of sewage pipes near Terrigal Beach as a source of beach water contamination; this finding drove a Council-led water quality improvement program that included remediation of 36 kilometres of local sewer mains.

This project, which involved one of Professor Seymour’s PhD students, was nominated for a 2023 Eureka Prize, highlighting how ocean microbiology research can assist governments and other stakeholders to better monitor and mitigate risks to human health.

For now, if you’re making plans for your first ocean swim of the season, Professor Seymour offers the following advice: don’t go to the beach after it’s been pouring with rain and don’t go swimming with open wounds (cuts, grazes) on your skin.

But perhaps most importantly, keep the risk in perspective and let researchers like Professor Seymour and his team take care of the rest.

“In Australia, the threat is still relatively low and pretty controllable,” he says.

We’re lucky to live near some of the world’s most beautiful coastlines. By taking a few simple steps to protect our health, we can keep enjoying everything our marine environments have to offer.

Interested in studying environmental consultancy and conservation?