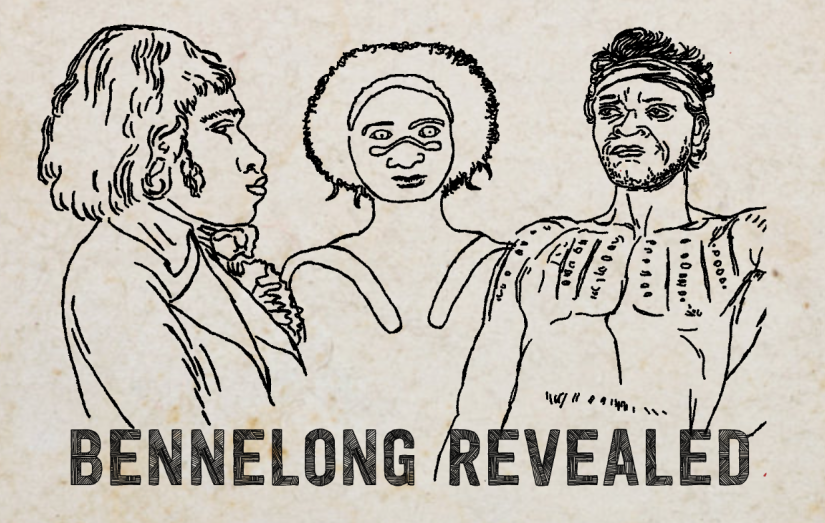

THE MAN BEHIND THE MYTH Woollarawarre Bennelong’s (1764-1813 - Wangal Tribe ) enigmatic life has at its heart, a story of origin and truth-telling. An individual embedded within ancestral traditional Lore, fated to play a key role amidst his Kin and those of the first British fleet. Bennelong’s story is a layered and complex narrative, offering us all the opportunity to reflect upon his legacy between two cultures, colliding within the pristine surroundings of (Warrane) Sydney Cove. A six-part podcast series which offers an Indigenous perspective about the life of Woollarawarre Bennelong. This six-part podcast series revisits the story of Bennelong through the lens of Indigenous oral culture, which has largely been excluded from contemporary Australian history.

Bennelong Revealed

#1 INTRODUCTION

During the lead up to 2020 and the anniversary of Cook coming to Australia a group of Historians and a filmmaker began to talk about the lack of knowledge of one of our significant men of Sydney Cove, Bennelong. What then was delayed through covid was a journey of discovery for a new narrative of working through the ideas and the myths behind the man Bennelong.

As a child Pauline had been told stories of Bennelong as a staunch man who was one of our first political prisoners, an international diplomat, a linguist and strategist. This worked against what she read as a teenager and so has always been passionate about making sure the oral histories come out about our influential men and women who where written into history from white lenses.

Bennelong’s history as written by white historians contains many untruths and reflects their lack of understanding of Aboriginal culture. Closer examination of the archives and Aboriginal oral history reveals a different version which deserves greater attention.

Why is it important to understand this story in 2023 – the year of the voice?

As a child Pauline had been told stories of Bennelong as a staunch man who was one of our first political prisoners, an international diplomat, a linguist and strategist. This worked against what she read as a teenager and so has always been passionate about making sure the oral histories come out about our influential men and women who where written into history from white lenses.

Bennelong’s history as written by white historians contains many untruths and reflects their lack of understanding of Aboriginal culture. Closer examination of the archives and Aboriginal oral history reveals a different version which deserves greater attention.

Why is it important to understand this story in 2023 – the year of the voice?

#2 BENNELONG - EARLY LIFE

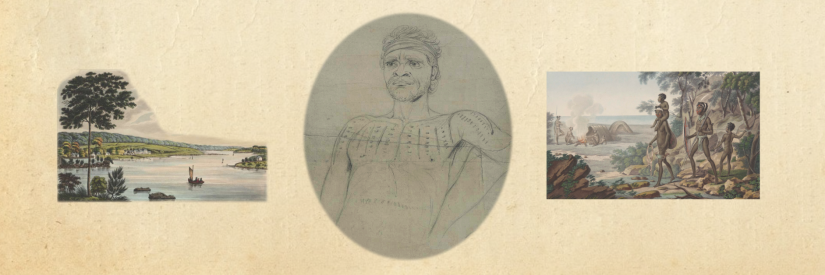

Woollarawarre Bennelong is one of the most widely known Aboriginal peoples associated with the Colonial settlement of Australia. His Name surrounds us in place names and commercial premises along the harbour. Born around 1764 in the Homebush Bay Area. A Wangal man we talk about what his childhood would have been like living on the estuary from Parramatta to Darling Harbour. He would have been around 6 when Cook sailed into Botany Bay.

We learn about his sisters and family, his totem name, which was said to be a fish, although no one knows the species. Travelling the harbour in his mother’s nawi (canoe). His custodial links to Me-mel (Goat Island) the eye of the eel, the creation story for the harbour.

We learn about his sisters and family, his totem name, which was said to be a fish, although no one knows the species. Travelling the harbour in his mother’s nawi (canoe). His custodial links to Me-mel (Goat Island) the eye of the eel, the creation story for the harbour.

#3 BENNELONG - CONTACT WITH THE COLONY

The new arrivals thought they were being greeted by women and men on their nawi’s. Chanting “warra warra” (go away).

Now in his twenties when the tall ships rolled in to Sydney Cove, Bennelong began his time with the colony as a prisoner in Governor Phillip’s house, along with Colebee. He quickly learned how to communicate with the foreigners and although he was able to escape, he came back, after consultation with other elders. He was given a hut on what is now called Bennelong Point and was by this time married to his second wife, Barangaroo a fiercely defiant woman who lived close by, but refused to engage with the colony.

Was he collecting information about the intentions of the colonists and reporting back to the nations of Sydney? He did have communication with other warriors especially Pemulwuy, and it seems that nothing happened entirely by chance in this early phase of colonial interaction.

Now in his twenties when the tall ships rolled in to Sydney Cove, Bennelong began his time with the colony as a prisoner in Governor Phillip’s house, along with Colebee. He quickly learned how to communicate with the foreigners and although he was able to escape, he came back, after consultation with other elders. He was given a hut on what is now called Bennelong Point and was by this time married to his second wife, Barangaroo a fiercely defiant woman who lived close by, but refused to engage with the colony.

Was he collecting information about the intentions of the colonists and reporting back to the nations of Sydney? He did have communication with other warriors especially Pemulwuy, and it seems that nothing happened entirely by chance in this early phase of colonial interaction.

#4 BENNELONG - IMPACT

The white perception of Aboriginal people was driven by a lack of understanding. Often described as savages, the importance of people like Bennelong were not recognised.

One of the worst examples is the awful obituary of Bennelong written by George Howe. Ironically penned at the time when white society was extremely violent, awash with alcohol, underwritten by slavery and colonisation, and held attitudes towards women which were highly discriminatory.

Bennelong’s passing made ‘front page news’, in a male dominated, white settlement at a time of rapid colonial expansion all of which was impinging on Aboriginal lands and values. This also meant that his graveside was not honoured and the search for his grave later gave rise to a questioning of the negative status implied to him by the colony.

One of the worst examples is the awful obituary of Bennelong written by George Howe. Ironically penned at the time when white society was extremely violent, awash with alcohol, underwritten by slavery and colonisation, and held attitudes towards women which were highly discriminatory.

Bennelong’s passing made ‘front page news’, in a male dominated, white settlement at a time of rapid colonial expansion all of which was impinging on Aboriginal lands and values. This also meant that his graveside was not honoured and the search for his grave later gave rise to a questioning of the negative status implied to him by the colony.

Oral history indicates that at the time of his death Bennelong was a respected senior elder, an image that simply does not match Howe’s obituary. But the false story of the written record controlled the narrative for the next 150 years and fiction became history.

From 1812 to the early 20th Century Bennelong’s grave site was ignored and ‘lost’. We knew it was somewhere on James Squires land but where? Clues in the archives enabled site identification which was supported by survey analysis of an early photograph of the grave. It is said that ‘White Australia has a black history’ – a true statement with a double meaning.

#5 BENNELONG - VOYAGE TO LONDON

The colony expanded and for the most part the Aboriginal people were ignored, but conflict over resources increased, and Bennelong realised that permanent change was underway.

Phillip returned to London taking Bennelong and Yemmerrawanne with him. A lot is known about their time in London through archived invoices of their spending and documentation of their music, but we do not have details of their discussions with important Britons.

Possibly the reason for them going was to meet with the king, but this did not eventuate. There were precedents for such a formal visitation from the colonies but this one played out differently. An alternative view is that the Aboriginal men were merely being taken to England as curiosities, but judging from the limited interest shown by the English press this seems unlikely and they were treated as important guests.

After Yemmerrawanne’s death Bennelong moved onto the ship for seven months, awaiting his return back to his country.

Phillip returned to London taking Bennelong and Yemmerrawanne with him. A lot is known about their time in London through archived invoices of their spending and documentation of their music, but we do not have details of their discussions with important Britons.

Possibly the reason for them going was to meet with the king, but this did not eventuate. There were precedents for such a formal visitation from the colonies but this one played out differently. An alternative view is that the Aboriginal men were merely being taken to England as curiosities, but judging from the limited interest shown by the English press this seems unlikely and they were treated as important guests.

After Yemmerrawanne’s death Bennelong moved onto the ship for seven months, awaiting his return back to his country.

#6 BENNELONG - NEW TRIBE, KISSING POINT

On his arrival back to Warrane (Sydney Cove) Bennelong quickly dropped his English veneer and drew together the remnants of different clans and created the Kissing Point Tribe. This action took place at the very time when the colony was on the point of insurrection and it can be seen as one of the first decolonising acts from an Aboriginal person.

Bennelong chose to meet his obligations to his own people and to limit further damage from the white invasion. At Kissing Point he had the support of his own people and of James Squire who has his own story which is yet to be told.

A proud warrior, highly respected elder, and political activist who endeavoured to come to terms with the white invaders. As growing numbers swarmed over the traditional lands, he retreated from a white society that he could see no future in.

The increasing frontier violence created a widening gap in the two histories of our country, that only truth telling can bridge.

Hopefully this series can help realign some of the oral and written histories to create a better understanding of both our voices in the shaping of our country and a better way to reconcile the truths of our nation.

Bennelong chose to meet his obligations to his own people and to limit further damage from the white invasion. At Kissing Point he had the support of his own people and of James Squire who has his own story which is yet to be told.

A proud warrior, highly respected elder, and political activist who endeavoured to come to terms with the white invaders. As growing numbers swarmed over the traditional lands, he retreated from a white society that he could see no future in.

The increasing frontier violence created a widening gap in the two histories of our country, that only truth telling can bridge.

Hopefully this series can help realign some of the oral and written histories to create a better understanding of both our voices in the shaping of our country and a better way to reconcile the truths of our nation.