Flash droughts are becoming more common in Australia

Flash droughts are becoming more common in Australia. What’s causing them?

Bogan river at Nyngan. Image: Adobe Stock

Flash droughts strike suddenly and intensify rapidly. Often the affected areas are in drought after just weeks or a couple of months of well-below-average rainfall. They happen worldwide and are becoming more common, including in Australia, due to global warming.

Flash droughts can occur anywhere and at any time of the year. Last year, a flash drought hit the Upper Hunter region of New South Wales, roughly 300 kilometres north-west of Sydney.

These sudden droughts can have devastating economic, social and environmental impacts. The damage is particularly severe for agricultural regions heavily dependent on reliable rain in river catchments. One such region is the Upper Hunter Valley, the subject of our new research.

We identified two climate drivers – the El Niño Southern Oscillation and Indian Ocean Dipole) – that became influential during this drought. In addition, the waning influence of a third climate driver, the Southern Annular Mode), would typically bring rain to the east coast. However, this rain did not reach the Upper Hunter.

Flash droughts are set to get more common as the world heats up. This year, a flash drought developed over western and central Victoria over just two months. While heavy rain this month in Melbourne ended the drought there, it continues in the west.

What makes a flash drought different?

Flash droughts differ from more slowly developing droughts. The latter result from extended drops in rainfall, such as the drought affecting parts of southwest Western Australia due to the much shortened winter wet season last year.

Flash droughts develop when sudden large drops in rainfall coincide with above-average temperatures. They mostly occur in summer and autumn, as was the case for Asia and Europe in 2022. That year saw flash droughts appear across the northern hemisphere, such as the megadrought affecting China’s Yangtze river basin and Spain.

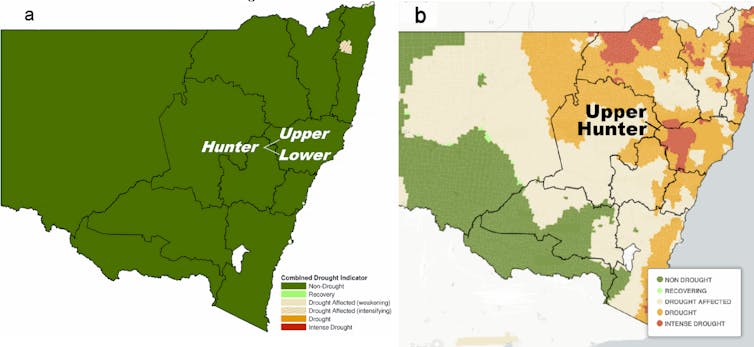

The flash drought devastating the Upper Hunter from May to October 2023 developed despite the region being drought-free just one month earlier. At that stage, almost nowhere in NSW showed any sign of an impending drought.

NSW Department of Primary Industries’ combined drought indicator in April 2023 (a) and combined drought indicator for May–October 2023 (b) show how rapidly a flash drought developed in the Upper Hunter region. Milton Speer et al 2024, using NSW Department of Primary Industries' data

NSW Department of Primary Industries’ combined drought indicator in April 2023 (a) and combined drought indicator for May–October 2023 (b) show how rapidly a flash drought developed in the Upper Hunter region. Milton Speer et al 2024, using NSW Department of Primary Industries' data

The flash drought greatly affected agricultural production in the Upper Hunter region, due to the region’s reliance on water from rivers. Low rainfall in river catchments means less water for crops and pasture. It also dries up drinking water supplies.

Flash droughts are characterised by abrupt periods of low rainfall leading to rapid drought onset, particularly when accompanied by above-average temperatures. Higher temperatures increase both the evaporation of water from the soil and transpiration from plants (evapotranspiration). This causes soil moisture to drop rapidly.

The Upper Hunter drought is part of a trend

Flash droughts will be more common in the future. That’s because higher temperatures will more often coincide with dry conditions, as relative humidity falls across many parts of Australia and globally.

Climate change is linked to shorter, heavier bursts of rain followed by longer periods of little rainfall.

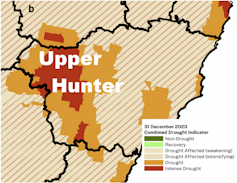

Intense drought conditions continued in the Upper Hunter in December 2023. Milton Speer et al 2024

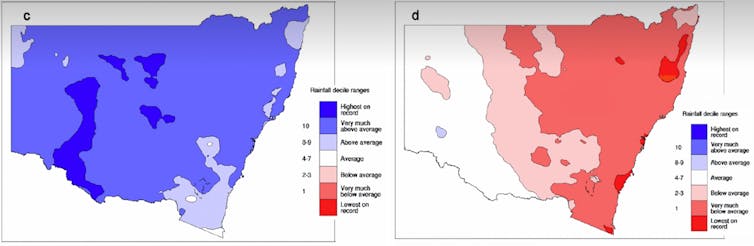

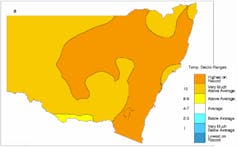

Intense drought conditions continued in the Upper Hunter in December 2023. Milton Speer et al 2024 The sharp drop in rainfall coincided with the Upper Hunter’s highest average maximum temperatures on record for May–October 2023. Milton Speer et al 2024

The sharp drop in rainfall coincided with the Upper Hunter’s highest average maximum temperatures on record for May–October 2023. Milton Speer et al 2024

In south-east and south-west Australia, flash droughts can also occur in winter.

In May 2023 rainfall over south-east Australia dropped abruptly. The much lower rainfall continued until November in the Upper Hunter. Over this same period, mean maximum temperatures in the region were the highest on record, increasing the loss of moisture through evapotranspiration. The result was a flash drought. While flash droughts occurred in other parts of south-east Australia, we focused on the Upper Hunter as it remained in drought the longest.

What were the climate drivers of this drought?

We used machine-learning techniques to identify the key climate drivers of the drought.

We found the dominant driver of the flash drought was global warming, modulated by the phases of the three major climate drivers in our region, the El Niño Southern Oscillation, Indian Ocean Dipole and the Southern Annular Mode.

From 2020 to 2022, the first two drivers became favourable for rain in the Upper Hunter in late winter through spring, before changing phase to one supporting drought over south-east Australia. Meanwhile, the Southern Annular Mode remained mostly positive, meaning rain-bearing westerly winds and weather fronts had moved to middle and higher latitudes of the southern hemisphere, away from Australia’s south-east coast.

Combined, the impact of global warming with the three climate drivers made rainfall much more variable. The net result was an atmospheric environment highly conducive to a flash drought appearing anywhere in south-east Australia.

Intense drought conditions continued in the Upper Hunter in December 2023. Milton Speer et al 2024

Intense drought conditions continued in the Upper Hunter in December 2023. Milton Speer et al 2024

Victoria, too, fits the global warming pattern

As for the flash drought that developed in early 2024 over western and central Victoria, including Melbourne, it continues in parts of western Victoria. The flash drought followed very high January rainfall (top 5% of records) dropping rapidly to very low rainfall (bottom 5%) in February and March.

It was the driest February-March period on record for Melbourne and south-west Victoria.

At the beginning of April, a storm front brought heavy rainfall over an 18-hour period to central Victoria, including Melbourne.

The rains ended the flash drought in these areas, but it continues in parts of western Victoria, which missed out on the rain.

The pattern of the 2024 flash drought in Victoria typifies the increasing trend under global warming of long dry periods, interspersed by short, heavy rainfall events. ![]()

Milton Speer, Visiting Fellow, School of Mathematical and Physical Sciences, University of Technology Sydney and Lance M Leslie, Professor, School of Mathematical and Physical Sciences, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.