Before the 1980s, Australian teachers could be banned for being gay

Before the 1980s, Australian teachers could be banned for being gay. A new report wants to protect them at religious schools too.

Greg Weir campaigned against his ban from teaching. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales and Courtesy SEARCH Foundation, CC BY

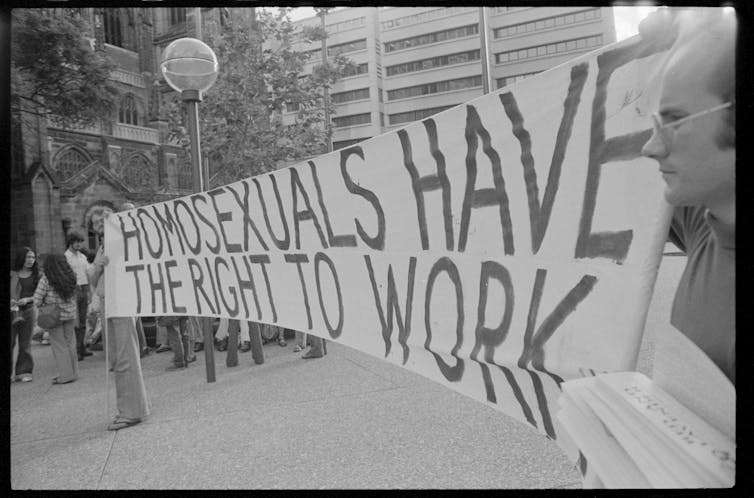

In 1976, Greg Weir was banned from teaching by the Queensland government because he was gay – and was then denied employment in New South Wales and Victoria for the same reason. Two years earlier, in 1974, New South Wales trainee teacher Penny Short was declared “medically unfit” to teach after publishing a lesbian poem.

This kind of discrimination in public schools has been outlawed, thanks (in part) to the activism of teachers like Weir and Short. From the 1980s, anti-discrimination laws made overt discrimination illegal in public schools. The exemptions to these laws for religious organisations in some states, however, allow discrimination to continue.

Today, in New South Wales, Western Australia, Queensland and South Australia, teachers in religious private schools can still lose their jobs if they are gay, lesbian, bisexual or queer, or if they are transgender or gender diverse. In New South Wales, nonreligious private schools also have the right to discriminate.

This week’s landmark Australian Law Reform Commission report on religious education institutions and discrimination has called for laws to be clarified, so religious schools nationwide can’t fire or refuse to hire teachers on the basis of their sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, marital status or pregnancy.

In our research on the histories of LGBTQ+ teacher employment, we have come across multiple, publicly known controversial sackings in the 1970s, as well as the more insidious practices of moving out (or outed) gay and lesbian teachers to administrative roles, away from students.

The several cases brought to the attention of activists and the media might only be the tip of the iceberg of homophobic discrimination in that period.

These teachers’ stories can help us understand why hostility to LGBTQ+ teachers remains such an entrenched problem today. And they allow us to appreciate the brave ways queer teachers have campaigned to protect themselves from discrimination.

Greg Weir campaigned against his ban from teaching. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales and Courtesy SEARCH Foundation, CC BY

Banned for being gay

In 1976, in the heat of Brisbane summer, Greg Weir made his way to the hall of his teaching college to find out what school he was posted to. Like all new teaching graduates on government-sponsored scholarships, he expected to learn where he would be teaching. But Greg wasn’t offered a teaching job, despite his scholarship.

The Queensland government had banned him from teaching because he was gay.

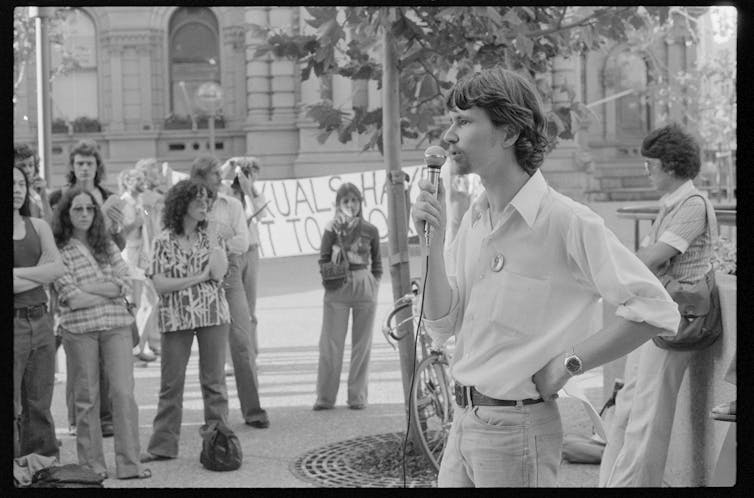

Following the Queensland Education Department’s refusal to employ him, Weir toured the country speaking on campuses and at lesbian and gay events, rallies and political events, auspiced by the Australian Union of Students. He took the Queensland government to court, but his case was ultimately withdrawn by 1984 because the Australian Union of Students ran out of money to fund it.

His visibility as an “out” activist placed him in the sights of the hard-right Queensland government, led by Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s Country Party and closely intertwined with new-right religious conservatives.

The Queensland Minister for Education made an unequivocal statement in 1976 about Weir’s prospects for employment as a teacher:

Student Teachers who participate in Homosexual and Lesbian groups should not assume they will be employed by the Education Department upon graduation from college.

Before this, the names of all members of the Kelvin Grove CAE Homosexual and Lesbian group were published in government gazettes.

Greg Weir toured rallies and events around Australia after being banned from teaching for being gay. Mitchell Library State Library of New South Wales, courtesy SEARCH Foundation, CC BY

Greg Weir toured rallies and events around Australia after being banned from teaching for being gay. Mitchell Library State Library of New South Wales, courtesy SEARCH Foundation, CC BY

Penny Short had already passed a required psychological check for teachers when she wrote a lesbian love poem for the Macquarie University student newspaper, Arena, published in 1974. She’d told the psychologist who assessed her she was in a relationship with a woman – and was told to stay in the closet.

But Short, like Weir, was out and proud about her sexuality. After the poem was published, she was referred back to the psychologist and declared “medically unfit” to teach.

In the case of Weir, a nationwide “Let Greg Weir Teach” campaign ran for over five years, from when Weir was banned from teaching. Weir also launched an unsuccessful legal case against the Queensland government. He was never able to take up a teaching job.

But Weir’s case made the issue of gay teachers central to the growing gay and lesbian movement.

Gay teacher and student activist groups (like GAYTAS, who campaigned for the rights of gay and lesbian teachers in schools and supported gay and lesbian students) were active in multiple states.

LGBTQ+ teachers’ rights today

Steph Lentz was sacked in 2021 for coming out as a lesbian.

Steph Lentz was sacked in 2021 for coming out as a lesbian.

Late last year, teacher Steph Lentz released her autobiography detailing her experience of being sacked in 2021, after coming out as a lesbian at the Sydney religious school where she taught. Despite pro bono legal support from Equality Australia, there were no legal protections Lentz could call on in New South Wales.

The following year, in 2022, a Senate inquiry heard testimony from multiple teachers about their experience of being sacked by religious schools because of their sexuality.

The New South Wales parliament is set to debate an Equality Bill that would (among many other reforms) remove the exemptions to anti-discrimination laws that allow religious and private schools to discriminate against these teachers on the grounds of religious belief.

Queensland and Western Australia are also considering changes to their laws.

These employment disputes are connected to very public and controversial debates surrounding gender and sexuality in schools.

For instance, much of the debate surrounding the ultimately successful Marriage Equality postal vote focused on whether such rights might lead to “boys wearing dresses” in schools and to “skin curling” conversations about gender – according to former Prime Minister Scott Morrison and broadcaster Alan Jones.

These Australian debates are occurring in the context of a global backlash against rights for trans and gender diverse people in particular, often focused on children, teachers and schools. As British sociologist Sally Hines has argued, contemporary anti-trans campaigns and laws resemble those targeted at lesbians and gays during the 1980s and 1990s.

Queer teachers, then and now

Teachers are often positioned as role models for their students. Therefore, they are expected to exemplify good moral character. Teachers have the capacity to shape the future of the children they teach – and more generally, of the nation.

This means queer and transgender teachers are particularly vulnerable to accusations of trying to influence children.

For instance, in the 1970s and 1980s, those advocating against Greg Weir and other queer teachers argued out gay and lesbian teachers would expose students to moral indecency. They suggested gay teachers would challenge the bedrock social institution of the family, and ultimately lead students to a life of “perversion”.

These “moral rights” campaigners pitched their cause as protecting children’s rights and interests, suggesting any other position would place children at risk.

The teachers, including Greg Weir, who ran campaigns to defend their right to teach in the 1970s and 1980s, were connected to broader gay liberation campaigns and gay and lesbian groups organised inside teacher unions. They gathered at conferences like the national Homosexuals at Work in 1978.

The queer teachers who defend their right to teach in the 1970s and 80s were connected to broader gay and lesbian groups. Mitchell Library State Library of New South Wales, courtesy SEARCH Foundation, CC BY

The queer teachers who defend their right to teach in the 1970s and 80s were connected to broader gay and lesbian groups. Mitchell Library State Library of New South Wales, courtesy SEARCH Foundation, CC BY

These teachers argued bans on gay and lesbians teaching in schools would force teachers into the closet, and prevent students from understanding sexual and gender diversity. They argued normalising discrimination in a school setting legitimises this discrimination, and produces violence against LGBTQ+ people. They advocated for liberalising sex education and normalising LGBTQ+ content in the curriculum.

They argued this awareness, rather than harming children, could help prevent harm.

The legacy of this history looms large for teachers. A recent study of the experiences of LGBTIQ+ teachers found they are still reluctant to be out in school settings: they are “haunted” by a history of education that equates their identities with “threats to children’s innocence”.

There is substantial evidence of LGBTQ+ teachers experiencing alienation, isolation and exclusion at work in religious schools, and persistent reporting of verbal and physical abuse directed at LGBTQ+ students in schools.

Returning to this history provides a way to understand how discrimination against LGBTQ+ teachers continues to be justified through references to the rights of children, such as in debates over the the federal Religious Discrimination Act or the New South Wales Equality Bill.

These notions are not new – they just have a new focus. The new report from the Australian Law Reform Commission provides an opportunity to address the harm done to LGBTQ+ teachers and students by discriminatory laws.

Note that we refer specifically to discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, trans and gender diverse teachers and students, and do not refer to intersex people. This is because current laws to do not exempt intersex people from discrimination protection in religious or private schools. Learn more here in the ALRC report.![]()

Archie Thomas, Chancellor's Research Fellow, University of Technology Sydney and Jessica Gerrard, Associate Professor, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.