Meta’s lost revenue is a huge hit for public interest journalism

Australia needs to prioritise finding new funding to support journalism, particularly in remote and regional areas, write Anna Draffin and Gary Dickson.

Picture: Adobe Stock

Public interest journalism was already under significant stress in Australia. And now the pressure is ratcheting up even further.

While still experiencing the pandemic’s aftershocks, the industry has simultaneously been hit with the increasing cost of doing business, rising costs of living and declining advertising spend. All of this has made it harder to report the news that matters, educates and informs.

With Meta announcing last week it will not renew its commercial agreements with news outlets in Australia – worth an estimated A$70 million per year – it’s not an understatement to say it’s been a bad time for journalism.

Where news in Australia is vanishing

Public interest journalism is a vital service in a healthy democratic society. It creates social cohesion, informs decision making and strengthens democracy.

The funding provided by tech giants under the agreements made as part of the landmark News Media Bargaining Code in 2021 provided a significant source of revenue for media companies.

One regional news company estimated in its submission to the Regional Newspapers Inquiry that once the agreements were fully implemented, the revenue would fund up to 30% of its editorial wages.

But as that money dries up, it’s clear Australia’s public interest journalism sector must find a new way to survive and thrive. And that method must be supported by data that clearly identifies the areas of Australia most lacking in comprehensive, accurate journalism.

The Public Interest Journalism Initiative (PIJI) has been tracking public interest news production in Australia since 2019, and our research reveals a clear divide across metropolitan and regional audiences and markets. Regional and remote areas of Australia have fewer news outlets generally, compared to areas along the east coast and around capital cities.

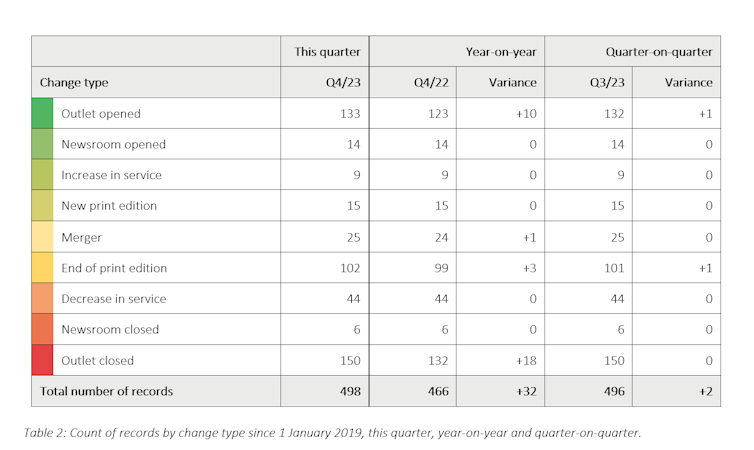

Overall, PIJI has identified almost 500 changes in news production around Australia since 2019, with the majority of these being contractions. This includes media outlets closing, shrinking their services or ending their print editions.

But the decline is not limited to rural and regional areas. Our data also identify thinning in metropolitan markets, with 135 contractions compared to 61 expansions. However, the data also suggest the nature of the changes in metropolitan markets is different from that of regional markets.

The changing Australian news landscape since 2019. The first column represents the total changes from 2019 to date; the second column reflects how many changes have occurred in the last year; and the third column reflects how many changes have occurred in the last quarter. Author provided

Fifty-three percent of contractions in major cities were local suburban newspapers ending their print editions and shifting to digital-only delivery. And just over a third of contractions were outlets that ceased operations altogether, a share that has been steadily increasing.

In regional areas, we’ve seen more substantial changes with outlets closing (51% of regional contractions) or decreasing their service by cutting the frequency of publications or the level of output (21%). The shifting of content from print to digital represented just 16% of the changes seen in the regions.

Concerningly, we have also identified areas where news is completely lacking – so-called “news deserts”. According to our latest quarterly data, there are no print, digital or radio local news producers in five Australian local government areas.

Excluding radio, we could not identify any print or digital local news outlets in 29 local government areas.

Many of those areas are regional and remote areas – highlighting once again the discrepancy between metropolitan and regional news coverage.

More data on the industry is vital

This data also underscores where future support should be directed.

Local and especially regional news urgently needs support in the face of significant industry upheaval and transformation. There is a clear need for long-term engagement and collaboration between government and researchers – both independent and government-based – given the complexity of issues facing the industry.

Longitudinal data and independent analysis will be of the utmost importance in this. Analysis must be at arms length from both government and industry, but should engage with each side, informed by daily practice and policy.

Impartial, third-party research will also assist with understanding and assessing the impact of any policy interventions, as well as tracking and informing industry transformation, whether that be changing business models or new start-ups.

We have known this for some time. In April 2022, the Regional Newspapers Inquiry pointed to the need for core, longitudinal industry data.

This is why PIJI has gathered timely data on market changes in news production across Australia, the location of these outlets and how they are connected with one another. This assists communities, researchers, industry leaders and policymakers to better understand the health of Australia’s news media landscape.

Such data can provide the impetus for policy decisions that will support news businesses and producers. Innovation is sorely needed in this area to address journalism’s broken business model.

What could help?

One potential new avenue of revenue would be the development of a not-for-profit journalism sector in Australia.

This has been repeatedly recommended in parliamentary and regulatory inquiries over the past decade. There is evidence from overseas, particularly the United States, to suggest a not-for-profit news sector would increase media diversity and address the lack of commercially viable options in investigative journalism or less-represented geographical, cultural and linguistic markets.

The Productivity Commission’s inquiry into philanthropy appears to be giving this option some consideration; its draft report, released last year, proposed extending deductible gift recipient status to public interest journalism. PIJI would welcome the support this could offer news producers and outlets.

There is also potential in commercial measures like research and development tax rebates for public interest journalism. Again, we can be guided by success overseas – Canada implemented a similar rebate system a few years ago.

Evidence and a clear focus on the role of news as a public good must lead the way in identifying paths forward to service our communities.

Maia Germano, a research coordinator at the Public Interest Journalism Initiative, contributed to this report.

Anna Draffin, Adjunct Professor, University of Canberra and Gary Dickson, Research fellow, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.