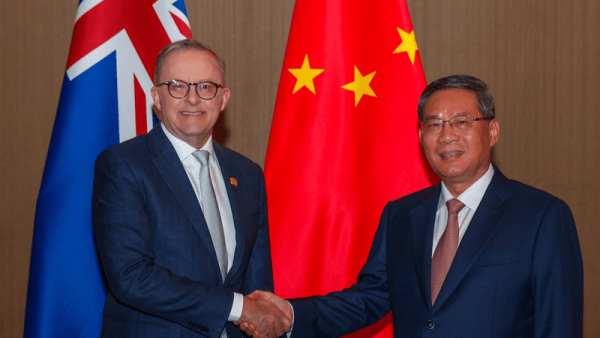

Little room for nostalgia on Albanese China trip

@AlboMP / X

Elena Collinson, Manager, Research Analysis, Australia-China Relations Institute, University of Technology Sydney |

This article appeared in Asialink's Insights on November 3 2023

The diplomatic symbolism of Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s visit to China is unmissable. Not only is this the first by an Australian leader after seven years of acrimony, it also comes almost 50 years to the day after Gough Whitlam became the first Australian leader to visit the communist nation.

It is also reflective of where the Australian Labor Party (ALP) now sees itself in relation to the China debate in Australia.

Since a pall was first cast over the general mood of optimism on China from 2016, and throughout the ensuing turbulence to 2022, the ALP tended to avoid overt reference to this part of Labor mythology. Once a cherished memory, Whitlam in China became an apparition to quietly avoid, as opposed to one readily invoked.

It was not always so. Writing in The Australian in 2012, Julia Gillard celebrated ‘40 years since the act of ‘reason, foresight and enlightened self-interest' – the act of leadership – which created the modern relationship’ between Australia and China. Her government was continuing Whitlam’s legacy on China, ‘crafting stronger co-operative government-to-government links’ and ‘[s]tronger bilateral architecture to better co-ordinate the breadth of our contemporary relationship’.

Likewise in 2014, in a speech to the House of Representatives welcoming President Xi Jinping, Bill Shorten highlighted that Whitlam had ‘ended a ‘generation of lost contact’ and began a thriving partnership now in its fifth decade’.

But this language of remembrance and the guiding principles adopted from the Whitlam era now assume a different tone and form. Labor has made a sharp rupture with those times. Whitlam has become history in the truest sense of the word: now archival, not actual.

Thus in delivering the 2022 Whitlam Oration, Foreign Minister Penny Wong distanced the ALP’s current approach to China from the moment of its inception under Whitlam: ‘Gough sought new relations with China. Fifty years on, we seek to stabilise relations with China.’ She added, ‘It is an insult to all Gough did to prepare us for the future if we act as though we live in a world that has long since passed.’

Then, marking the 50th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between Australia and China in December, Prime Minister Albanese was similarly circumspect, writing, ‘We are always going to be better off when we engage in dialogue. When we talk to each other calmly, directly and in a spirit of respect. That was the basis for establishing our diplomatic relations in 1972.’

The Albanese government has made it clear, both in rhetoric and in substance, that there will be no return to the euphoria that characterised the Whitlam years.

China, as Albanese said in his first month in office, ‘will be a problematic relationship’ for some time. It has been ‘explicit’, the Prime Minister told the US State Department at the end of last month, that ‘it does not see itself as a status quo power’, giving rise to the need for like-minded nations to ‘work together and protect’ the international rules-based order. The era of great power rivalry allows little time for wistful nostalgia about easier diplomatic times, when Whitlam could boast the strategic judgment that Australia faced no foreseeable threat for the next 10-15 years.

The government has steadfastly adhered to the blueprint crafted by its conservative predecessor, manifest most clearly by its full-throated support for the AUKUS trilateral security partnership and acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines, the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad), strengthened defence relations with Japan, and the agenda for reform of Australian defence posture and structure, contained in April’s Defence Strategic Review.

Nor can it revive the era of optimistic engagement, conditional as it was on the confluence of circumstances absent today.

Consider the times in which Whitlam made his great diplomatic leap to China. In the early 1970s, the Cold War was virtually ending in East Asia even as it continued to rage in Europe. Leaders in Canberra and Washington, despite their ideological differences, welcomed the new space for creativity in their foreign relations. Whitlam and Nixon, after all, were moving in the same direction on China. Whitlam wanted an Australian foreign policy less based on ideological considerations and military alliances. It allowed for talk, revealed in University of Sydney historian James Curran’s book Australia’s China Odyssey (UNSW Press, 2022), of a ‘new international outlook’ and a ‘new era of regional belonging’ with the opening to China as the central symbol of this aspiration. Whitlam even spoke of America and Britain not as great and powerful ‘friends’ but as great and powerful ‘associates’.

But in 2023, a new cold war between the US and China is well underway, with Asia its epicentre. Albanese leads a government that he has characterised as ‘pretty much in lockstep’ with the US. It is a government that has committed to moving beyond interoperability to what Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister Richard Marles labels ‘interchangeability’ between Australian and American forces. As Wong enunciated in a pre-election debate, the ALP has shelved the John Howard-era formulation that ‘Australia doesn’t need to choose between the US and China’. She said, ‘We have already chosen.’

There is also a marked difference in the international outlooks of the leadership at the helm of the PRC now and then. Mao Zedong and Xi both invoked China’s ‘century of humiliation’ as a key part of a historical narrative legitimising and reinforcing one-party rule, but for different ends. As one Chinese studies professor notes, Mao used the narrative to emphasise the Communist Party of China’s (CPC) ‘singular and salvatory role in the lives of the Chinese people’, underlining the CPC’s responsibility for having moved the nation past its years of ignominy. Xi, on the other hand, has reshaped the narrative to support the call for ‘the great rejuvenation of the Chinese people’, advocating for ‘a return to China’s glorious past, moving the Chinese people from humiliation to a resurgence’. Beijing has used this to justify an increasingly assertive – and in some instances, aggressive – international posture, not least in its actions in the South China Sea. This nationalist grievance is roiling regional and global politics.

The challenge for the present, then, is how, if at all, the Australia-China relationship can move beyond ‘stabilisation’. Chinese officials have called for the relationship to ‘advance’, claiming it has already ‘stabilised, improved and developed’. Australian representatives remain rather more reticent.

Both sides have worked towards cultivating a climate of goodwill in the weeks immediately preceding and following the confirmation of the visit. The Australia-China High Level Dialogue resumed, with the Australian delegation receiving a warmer than anticipated welcome in Beijing. Australian citizen Cheng Lei was released after three years of detention by China. Beijing lifted its trade restrictions on Australian barley and hay exports and commenced a five-month review of its punitive tariffs on wine. Around the same time, Canberra decided that the 99-year lease of the Port of Darwin could remain with a Chinese company and made a preliminary recommendation for the cessation of anti-dumping duties on China-made wind towers.

But these developments, positive as they are, simply return Australia-China relations to a more normalised state as opposed to progressing them. It would seem that Mr Albanese is keen to not get too far ahead of public sentiment which, judging from recent opinion polls, shows every indication of remaining both wary and suspicious of China’s ultimate intentions when it comes to regional stability.

Author

Elena Collinson is head of analysis at the Australia-China Relations Institute, University of Technology Sydney.