Rising tides, shifting sands: Rethinking Australia’s foreign policy towards China

DaiLuo / Flickr

Marina Yue Zhang, Associate Professor – Research, Australia-China Relations Institute, University of Technology Sydney |

This article appeared in the Australian Institute of International Affairs’ blog, Australian Outlook, on April 21 2023.

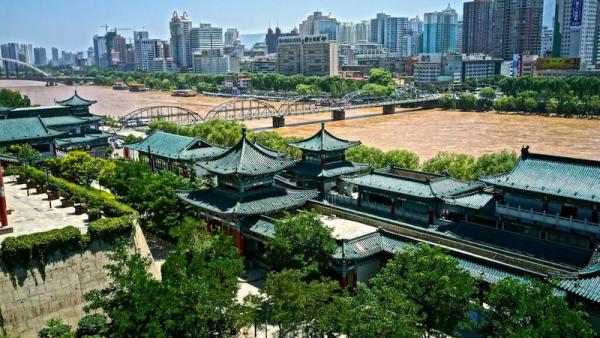

I recently returned from China, the first visit to my homeland since the outbreak of Covid-19. I went to three cities: Beijing, Guangzhou, and Lanzhou. Beijing, the nation’s capital and an innovation hub, epitomizes modern China. Guangzhou, a bustling first-tier city, displays a mix of contemporary and traditional elements and represents entrepreneurship and private enterprise. Lanzhou, a second-tier, provincial capital city in a less-developed province in the northwest, has one of the lowest levels of GDP per capita among major cities, which is reflected in consumer habits and lifestyle choices. The country, and those cities where I spent most of my youth, have changed markedly in the past three years and are very different to what is reported in the West.

In all three cities, infrastructure and urban landscapes have improved dramatically. The roads are now filled with domestically manufactured vehicles, especially electric vehicles (EVs). Approximately 60 percent of public transportation, including taxis, ride-hailing cars, and buses, are EVs or other new energy vehicles. Cash has virtually disappeared, and so has petty crime, thanks to extensive surveillance camera coverage. Chinese youth are increasingly favouring local brands for clothing, footwear, accessories, cosmetics, and electronic products. They shop through live-streaming e-commerce on digital platforms like Taobao and emerging ones like Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok).

While Google, Facebook, and ChatGPT are unavailable in China, local alternatives offer comparable services. Beidou, China’s GPS equivalent, provides more accurate navigation services for users. Numerous services have also been digitalised, including ‘health declaration’ procedures for international travellers when exiting the country. China has advanced its applications in communications, surveillance, financial services, and smart city infrastructure, due to the lessons learned from dealing with lockdowns and mobility tracking during the Covid-19 pandemic.

While it is challenging to summarise the entire scope of the transformation, there are discernible themes and viewpoints that represent public sentiments in post-Covid-19 China, at least online.

Nationalism and pride cover a considerable portion of the discourse on the Chinese internet and celebrates China’s rise as a global power. Many people see China’s rise as a means to reclaim its historical status and rectify past humiliations. On geopolitical competition, discussions often touch upon the country’s growing influence and competition with the United States and other Western countries. The majority approves the government’s more assertive stance in international affairs. The last is global perceptions. Many Chinese internet users are keenly aware of how the world perceives China’s rise and its global role. They discuss the stereotypes, misunderstandings, and concerns that often dominate Western media coverage in the context of ‘East rising and West falling.’

It is essential though to be cognizant that the online discourse is under tight internet control within the ‘Great Firewall,’ which allows the Chinese government to monitor and control online discussions, filtering out content critical of the government or touching on sensitive topics. This level of control has led to a unique internet culture, where people are more cautious about expressing opinions or discussing certain issues. They may also rely on coded language or memes to share their thoughts to avoid drawing the attention of censors.

The Chinese government envisions a world of national Internets, with government control justified by the sovereign rights of states. Those who do not agree with such control choose to remain silent; those who support the government’s actions are not shy about sharing their applause for China’s economic rise, diplomatic victories, and suspicion of foreign influences.

Censorship in education, especially in the higher education sector, has been a tool that limits the scope of information and ideas available to Chinese youth. Content in TV programs, movies, and even games that is deemed politically sensitive, morally inappropriate, or harmful to social harmony must obtain approval from the government’s regulatory body, which can no doubt limit the range of ideas and perspectives explored in Chinese creative industries.

The impact of censorship is most concerning for the younger generation. It can lead to a lack of exposure to alternative viewpoints and potentially foster an environment where critical thinking and open debate are discouraged. Without developed worldviews, the younger generation can easily be brainwashed by public discourse online and through education. For instance, Vladimir Putin is praised for his assertiveness, and the implications of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are downplayed.

As a result, most students today are concerned more about their personal life. This is compared to 30 years ago when I was a student at Peking University and students were concerned about the future of the country. It is difficult to blame them: without exposure to a range of diverse perspectives and narratives, many young people feel that they are trapped in an endless cycle of self-improvement and competition, which often leads to burnout, anxiety, and depression. The word ‘involution’ – or ‘neijuan’ (内卷) in Chinese – best describes the phenomenon of intense competition and excessive workloads in education, work, and social life among youth.

Alongside the positive aspects of China’s rise, many internet users also recognise the challenges the country faces, such as income inequality, environmental degradation, corruption, and the need for political and social reform. People I met during my visit talked about the domestic challenges China is facing in relation to long-term stability and growth. For example, consumers are more cautious in their spending due to decreased incomes, and private businesses that once relied on government revenue now face dwindling profits as local government budgets shrink.

Disparities between regions and cities are evident but manageable, largely due to constraints on mobility such as the ‘hukou’ system – a residential permit linked to things such as property purchases, ride-hailing driver licenses, and children’s schooling. However, disparities among different ‘classes,’ whether based on wealth, education, or career within a city are tearing China’s societies apart.

Living under the watchful eyes of ubiquitous surveillance cameras, and the constant supervision of ‘internet nannies’ employed by the government and platform companies on social media, might provide an illusion of safety. However, it is akin to living in a fishbowl. The tight control by the government is a double-edged sword: it may create a harmonious environment and ensure that people have the information the government wants them to have; on the other hand, it might drive those who do not like this system away from the country. The increasing number of rich Chinese emigrating to Singapore is a manifestation of the latter.

Over the past three years, China has undergone significant transformations. During my previous research trips exploring China’s innovation policies and practices, I was usually greeted warmly by the people I was interviewing. However, on this trip, as a Chinese Australian, I encountered occasional suspicion and remarks such as ‘Australia should be punished’ for siding with the United States. These changes can be ascribed to both the West and to China: the West has realised that they cannot reshape China to reflect their own values, and thus view China’s rise as a threat; meanwhile, China has become increasingly assertive in determining its political, cultural, and economic future based on its own principles.

Australia’s foreign policy towards China is a delicate balancing act. As the world continues to evolve, the relationship between China and the United States plays a significant role in shaping the global geopolitical landscape. Australia needs to navigate these complexities carefully, ensuring that its diplomatic, economic, and strategic relationships with both countries are maintained and prioritised based on its national interests. To achieve this, Australia needs to engage in regional and multilateral forums, strengthen cooperation with other countries in the intermediate zone.

Author

Dr Marina Yue Zhang is Associate Professor – Research at the Australia-China Relations Institute, University of Technology Sydney.