Aukus isn’t enough to secure the region’s prosperity – there is still much more work to be done

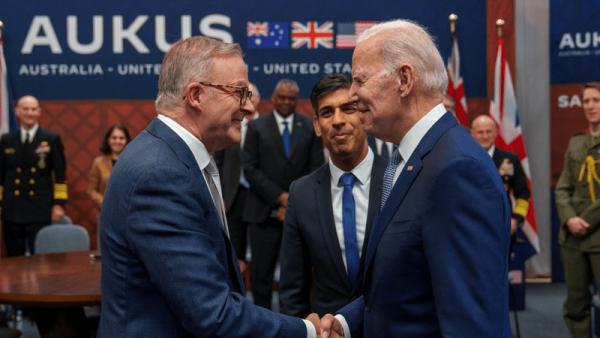

@AlboMP / Twitter

James Laurenceson, Director, Australia-China Relations Institute, University of Technology Sydney |

This article appeared in The Guardian on March 18 2023.

With the announcement of an ‘optimal pathway’ for Australia to acquire nuclear-powered submarines now behind us, there’s no sign of Beijing changing its approach to the bilateral relationship: much grumbling about Aukus but not much else.

This was the expectation ahead of the announcement.

Last year, Canberra and Beijing agreed to re-engage in full awareness of their differences – even ‘disputes’, the Chinese ambassador remarked – but also accept that these should not stop the two sides pursuing areas of mutual benefit.

The diplomacy of the Albanese government, which turned a corner on the relationship dysfunction under the Morrison government, has once again been on display.

At no point in the Aukus announcement did Canberra seek to poke Beijing in the eye, shying away from even mentioning China. Indeed, Beijing was offered a briefing ahead of the public announcement.

So, now the challenge becomes a longer-term one.

Last week former prime minister Paul Keating claimed the Australian government has ‘screwed into place the last shackle in the long chain the United States has laid out to contain China’. That is, a US-led plan whereby ‘1.4 billion of those Chinese, should keep their place’.

Aukus is meant to be about acquiring a deterrent that will limit China’s ability to exercise its immense power in a way that hurts Australia’s interests. This is, of course, prudent.

But leave aside the question of whether Aukus, in fact, delivers deterrence. (We know the first Aukus submarine will not be available for at least 15 years, and even then, how a few conventionally armed, Australian-commanded ones will make any difference to the overall balance of capabilities between two nuclear-armed superpowers has never been explained.)

An even more important realisation is that not everything can be deterred or contained.

Neither Beijing, nor the general Chinese public, would accept being told their economy cannot keep growing, or that they must forever content themselves with inferior living standards. Current per-capita income levels in China are still less than 30% of those in the US.

Another example: if Washington moved to recognise Taiwan as an independent state tomorrow, experts on cross-strait relations are in overwhelming agreement that Beijing would feel compelled to act, irrespective of the risks, and likely with brutality.

What this means is that Aukus isn’t nearly enough to secure Australia’s or the region’s prosperity and security.

Deterrence must be matched with reassurance – reassurance to Beijing that, irrespective of what the US (or the UK) might do, Australia is not interested in containing China’s economic rise, nor abandoning its One China policy.

Delivering this suite of reassurances will be difficult, not least of all because Beijing has paranoid tendencies, such as seeing ‘foreign forces’ behind domestic unrest everywhere from Xinjiang to Hong Kong. But it is not impossible.

It will be difficult because unlike conventionally powered submarines, nuclear-powered ones have obvious relevance for a Taiwan Strait contingency – or perhaps one in the South or East China seas. Indeed, Australia’s defence minister has openly stated an intention to acquire ‘impactful projection’, rather than simply defend Australia’s maritime approaches.

The one big advantage Australia can parlay is its track record, which contrasts significantly with America’s. The Trump administration was explicit in its intention to keep China subordinate in its own region. And in terms of policies, the Biden administration has only gone further. Last October, it cut off China’s access to advanced semiconductors in a move that Australia’s trade minister described as ‘draconian’.

Over the last 50 years, Australian governments of both persuasions have consistently welcomed China’s growing wealth. There’s been no change of late.

Earlier this month, when asked how to respond to an increasingly assertive China, Australia’s ambassador in Washington, Arthur Sinodinos, stated, ‘I think the first thing to say is that I start from a proposition that a strong and prosperous China is in everybody’s interest.’

And whereas Beijing now assesses Washington to be ‘fudging’, ‘hollowing out‘ and pursuing a ‘fake‘ One China policy – in essence, encouraging Taiwanese independence – the Australian foreign minister, Penny Wong, has given no such signal.

The diplomatic challenge then will be to convince Beijing that Aukus is simply a continuation of Australia’s long-term practice of welcoming China’s rising prosperity and pursuing economic engagement, while simultaneously hedging in the security realm. Beijing may not like this, but it is hardly surprising or exceptional.

Policy steps can give credibility to well-crafted messaging. Initiating discussions with China on joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership if it is prepared to meet its high standards is one example.

The challenges are clear. Still, compared with actually acquiring nuclear-powered submarines, managing the China relationship might be the easy part.

Author

Professor James Laurenceson is Director of the Australia-China Relations Institute at the University of Technology Sydney.