The right to not be extinct

This week AI industry leaders admitted that AI poses an extinction risk. ‘Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks, such as pandemics and nuclear war,’ said the group, which includes OpenAI CEO Sam Altman.

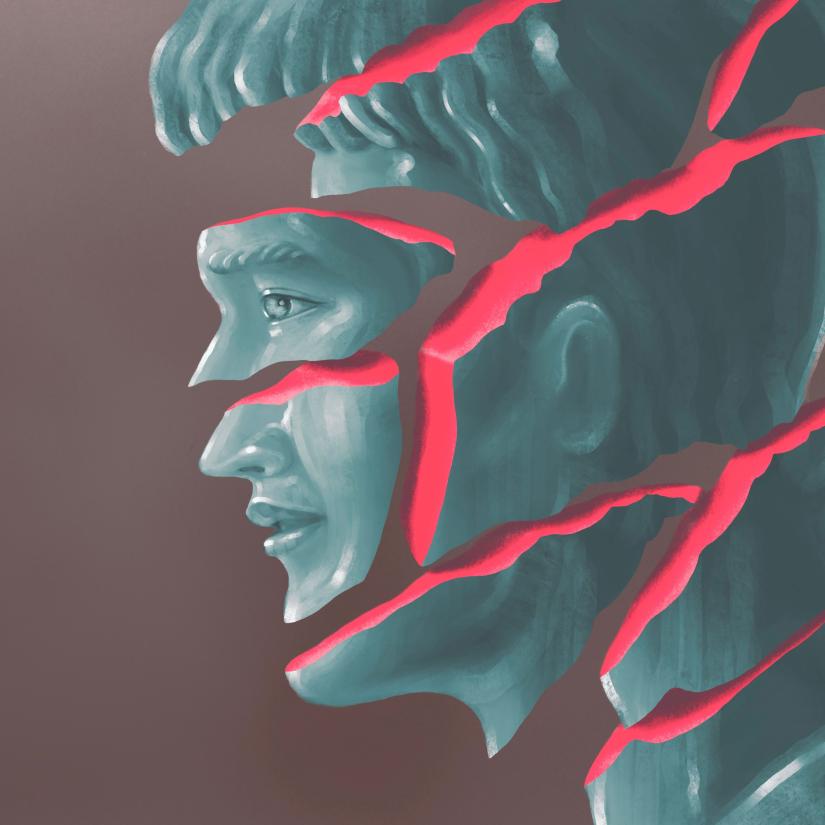

Ok, let’s think this through. Let’s say you have a machine that generates text and images based on all the content that’s out there on the internet. If your machine spreads defamatory lies that someone has been in prison, when in fact they haven’t, are you responsible? If your machine copies the work of artists who don’t want to be copied, are you responsible? And if your machine leads to, um, the extinction of humanity, are you responsible?

Regulators globally are recognising it’s time to act. Yesterday, the Department of Industry, Science and Resources released a discussion paper on supporting responsible AI. The paper nominates misinformation as a key issue, and in an interview with Sabra Lane on AM, Industry and Science Minister Ed Husic singled out the protection of news as a particular concern. Even big tech is now calling for regulation. Last month, OpenAI’s Sam Altman told US Congress that guardrails were needed in the form of an AI regulatory agency and mandatory licensing for companies.

That would be a start, and here are two more ideas. First, as I wrote in 2020 in relation to privacy, the law needs a straightforward way to apportion an appropriate degree of responsibility to the digital services that cause the harm. The same is true for AI. To achieve this, we should switch from a caveat emptor (buyer beware) approach to a caveat venditor (seller beware) approach. Instead of putting the responsibility on users for their treatment, digital platforms ought to bear responsibility for how they treat consumers. For one thing, this would mean that section 230 of the US Communications Decency Act, which gives digital platforms immunity from responsibility for content on their sites, needs to be completely redrafted.

Second, this responsibility can be meted out in the form of general principles. Instead of articulating all the minutiae in an attempt to cover every future innovation, for instance, let’s mandate fairness and outlaw coercion. Such an approach recognises that legislating at the micro level is tricky. Rather, let’s legislate larger, sweeping provisions. In some cases, the law already does this, including prohibitions in the Australian Consumer Law against ‘misleading and deceptive’ conduct. Indeed, one of Australia’s biggest privacy wins came last year, when the Federal Court ordered Google to pay $60m in penalties for making misleading representations about the collection of location data. Further provisions in the law could buttress consent, mandate fairness, outlaw coercion and mandate a degree of transparency.

For now, Europe leads the way with digital regulation. In 2018, it implemented the GDPR to protect privacy, which last week saw Meta fined 1.2 billion Euros for mishandling consumer data. Last year – as Michael mentions above – it implemented the Digital Services Act, which imposes obligations on platforms for mitigating risks related to the spread of harmful and illegal content. And now there’s an AI Act in the works - about which Altman has expressed some concerns. In the face of an ‘extinction risk’, Europe’s response hardly looks like regulatory overreach.

Sacha Molitorisz - Senior Lecturer, UTS Law

This article is from our fortnightly newsletter published on 2 June 2023.

To read the newsletter in full, click here. Subscribe here.