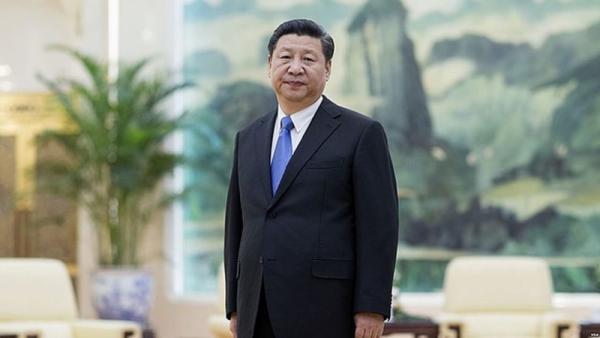

Xi Jinping: Prince or party man?

Marlin360 / Shutterstock

Michael Clarke, Adjunct Professor, Australia-China Relations Institute, University of Technology Sydney |

This article appeared in The Diplomat on November 4 2022.

Most observers agree that Chinese Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary Xi Jinping presided over a 20th Party Congress that confirmed his dominance of the party. Such is this dominance that it is something of a conventional wisdom to describe him as either Mao Zedong reincarnated or a new Chinese ‘emperor.’

Some believe this dominance may contain within it the seeds of the party-state’s undoing. Meixin Pei argues that as Mao himself demonstrated, ‘While trampling institutional rules and norms may benefit autocratic rulers, it is not necessarily good for their regimes.’

So has Xi now set himself above the CCP? Or does he remain a party man? In other words, does Xi’s personal ambition diverge from, or align with, that of the CCP itself?

This is an important question as one can make a case that power political calculations have contributed to Xi’s consolidation of his personal position of power within the CCP. But we should also recognize that the way in which this goal has been obtained (e.g. via a return to ideological rectification and discipline) has arguably strengthened the party’s cohesion and institutional strength.

Given the inscrutability of Chinese elite politics and the increasingly limited access external analysts have to China itself, there has been a temptation to rest explanations on ‘Pekingological’ readings of elite politics or by parsing the ideological tea leaves. While such approaches can yield important insights, they also carry risks. Witness, for instance, some of the overheated speculation prior to the 20th Party Congress about an emerging ’split’ within the top level of the CCP between supposedly ‘reformist’ or ‘technocratic’ elements associated with Premier Li Keqiang on the one hand, and Xi’s more ideologically committed retainers on the other.

But China, as Frederick Tiewes observes, ‘is not a totally unique political system where broader comparative considerations of bureaucratic interests and conflict structures are irrelevant.’ Politics in China – as anywhere else – is about conflict, and policy outcomes are as much about how such conflict is mediated through organizational, institutional, and bureaucratic processes.

In fact, as new waves of scholarship on post-Mao CCP elite politics suggests, the politics of leadership transitions have been driven by the ‘brass knuckles’ affair of who retains or gains power, and have not intrinsically been about ideological differences.

Indeed, Guoguang Wu persuasively argues that the core tension within the party under Xi has not revolved around ideological differences at all, but rather over different approaches to the ‘two fundamental institutional characteristics of the CCP regime.’ These are the Leninist drive for the leader to ‘rely on a purge of his rivals and promotion of loyalists’ to both consolidate power and implement policy, and the ‘built-in self-contradiction’ of a partially marketised economy and the CCP’s monopoly on political power.

The core distinction between Xi and his predecessors, then, is how to resolve or at least manage this contradiction:

From Deng Xiaoping through Jiang Zemin and to Hu Jintao, the CCP leaderships prior to Xi chose to promote market capitalism to maintain the CCP dictatorship. But Xi sees huge pitfalls in market capitalism for his regime and, accordingly, he is determined to struggle against these pitfalls to preserve the CCP dictatorship.

For much of the post-Mao era, the CCP’s capacity to mediate the contradiction between market capitalism and continued one-party rule was seen to lie in ‘performance legitimacy’ (via the delivery of continued modernization and economic development). But even under Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao this was no longer seen as sufficient; both sought the ‘adaptation and innovation of party ideology as the main resource for relegitimising CCP rule.’

Xi’s approach to resolving this fundamental contradiction has been to tilt the balance further in favour of the Leninist side of the equation. At the 20th Party Congress, Xi had both his personal political predominance and the correctness of his political ‘line’ affirmed. His predominance was underlined by the fact that he effectively stacked the Politburo Standing Committee – the seven men at the apex of the party’s decision-making apparatus for the next five years – with those known to have strong personal or professional ties to him.

In doing so, as witnessed by the omission of figures connected to the so-called Communist Youth League faction associated with former General Secretary Hu Jintao from the new Central Committee, like Premier Li Keqiang and former Vice Premier Wang Yang, Xi removed any remaining semblance of the factional balancing within the top level of the CCP that has prevailed for the majority of the post-Mao era.

Meanwhile, Xi presided over amendments to the CCP constitution that incorporate some of his key ideological precepts and policy priorities. The amended Party constitution now enshrines the ‘two establishes,’ which establish the status of Xi Jinping as the ‘core’ of the CCP and establish the guiding role of ‘Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for the New Era.’ It also hails Xi’s drive since 2012 for greater party discipline and ‘rigorous self-governance’ as necessary to ‘forge’ the ‘good steel’ required for the party and country to face the ‘situation of unparalleled complexity’ and ‘fight of unparalleled graveness…in promoting reform, development, and stability.’

Some may argue that the continued focus on ideological discipline is simply a means of ensuring Xi’s personal position of power. But it is also necessary to note that it has wider political resonance within the CCP.

Here, it is significant that Xi’s report to the 20th Party Congress pointedly foregrounded its discussion of this topic by referring to the parlous state of ideological discipline and the pervasiveness of ‘hedonism’ and ‘extravagance’ before the start of the ‘new era’ (i.e. the start of Xi’s first term). This clearly demonstrated Xi’s identification of his predecessor Hu Jintao as presiding over the flowering of ‘serious hidden dangers in the party, the country, and the military,’ and underscored what Xi (and arguably the CCP more broadly) sees as the secret for the party to ‘escape the historical cycle of rise and fall.’

‘The answer’, Xi has concluded, ‘is self-reform.’ Only by continuing to ‘purify, improve, renew, and excel itself’ can the CCP ensure that it ‘will never change its nature, its conviction, or its character.’

Undoubtedly, the ‘return’ of ideological discipline as a preeminent concern under Xi has been an instrument through which he has consolidated his personal power and authority within the party via the purging and disciplining of real or potential opponents.

Yet the desire for a return to ideological discipline within the CCP was already evident prior to Xi’s ascendance. There have arguably been multiple motivations – a desire to rein in perceived autonomy of local cadres, address public anger at endemic corruption, and reassert party oversight of an increasingly complex policymaking process – behind the ‘return’ to ideological discipline.

One can certainly make a case that these motivations have contributed to Xi’s consolidation of his personal position of power within the Party. But a concomitant effect of this renewed ideological discipline is to strengthen the cohesion and institutional strength of the party itself thereby providing it the necessary ‘infrastructural power’ to ensure its survival. In doing so, Xi’s personal ambition may thus ultimately complement rather than detract from that of the CCP’s core objective: to maintain its monopoly on power.

Author

Professor Michael Clarke is an Adjunct Professor at the Australia-China Relations Institute at the University of Technology Sydney.