How good is the TPP? Look to China for an answer

James Laurenceson, Deputy Director, Australia-China Relations Institute, University of Technology Sydney |

This article appeared in ABC's The Drum on May 22 2015.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) is nearly drafted. Australia is negotiating with 11 other countries, which has led to Trade Minister Andrew Robb recently describing it as a “free trade agreement times 12” and one that carries “transformational promise”.

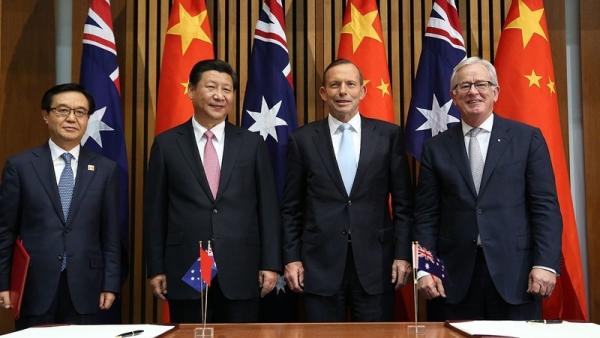

But to see how it stacks up, try putting it next to that other big deal Robb successfully struck and which is expected to be signed later this year, the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement (ChAFTA).

First there’s the matter of exposure.

In 2013-14, TPP countries bought $105 billion worth of Australia’s exports. China bought $108 billion.

Over the past five years, the average annual growth rate of exports to the TPP block has been a nice round number: precisely zero. To China it’s been nearly 20 percent.

OECD forecasts leave the TPP looking like an agreement between a group of countries whose global economic influence is in long term decline. By 2030, the five largest TPP countries – the US, Japan, Mexico, Canada and Australia – will have a 30 percent share of world GDP, down from 36 percent now. The share of China and India will grow from 25 percent to 34 percent.

Next compare the concessions on offer.

Australia already has FTAs with eight of the 11 TPP members. The three countries we don’t have deals with – Canada, Mexico and Peru – account for less than 3 percent of our exports to the TPP block. In other words, if the TPP is going to deliver fresh benefits to Australia, it will need to come in the form of hefty concessions from the likes of the US and Japan.

The US insisted on leaving sugar out of the bilateral deal back in 2004. Is it now on the table? What about rice, wheat, beef and dairy in Japan? The fact that TPP negotiations have continued for more than five years and 20 rounds strongly hints that it won’t be an “all in” affair.

Now take a look at what the FTA with China delivers. The World Trade Organization says that of China’s 8198 tariff lines, only 8.4 percent are duty free. But upon signing, the share of Australia’s exports entering China duty free will jump to 85 percent. That rises to 95 percent on full implementation. Tariffs as high as 30 percent on beef, dairy, seafood and horticulture will be eliminated.

Economic modelling published last year by the East-West Center said that in 2025 Australia’s GDP would be 0.5 percent higher with a TPP. That compares with the 0.7 percent boost that ChAFTA will provide, according to the Centre for International Economics.

Finally, think about what Australia gives up.

The FTA with China raises the screening threshold for private investors from $248 million to $1.08 billion. It also gets rid of tariffs on imports of textiles, clothing, footwear and cars. There’s nothing in that list that goes beyond what we already offer the US, Japan and New Zealand.

No ground was given on investment by Chinese state-owned companies: all must still go to the Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB).

No deal was made on purchases of rural land or agribusinesses. In fact, Australia’s FTA with the US means that American buyers can now purchase rural land with a value more than 70 times higher than those from China without needing FIRB approval.

The TPP on the other hand is set to introduce tougher rules on intellectual property (IP) and in other areas not usually covered in trade agreements. We already forfeited an additional 20 years of copyright protection to get the FTA with the US done a decade ago. As the Productivity Commission has repeatedly warned, that’s a problem because Australia is a net importer of IP. No such worries in the deal with China.

Author

Professor James Laurenceson is Deputy Director of the Australia-China Relations Institute at the University of Technology Sydney.