Risky business

In 1991, Professor David Eager experienced a near fatal car crash. The accident prompted him to enroll in a PhD that ultimately led to a career dedicated to saving lives and preventing injuries through managing risk.

Professor David Eager has been an academic at UTS for 27 years. Photo: Jacqueline Middleton

Professor of Risk Management and Injury Prevention, David Eager is an internationally recognised expert on the safety aspects of trampolines, playgrounds, play surfacing, sport and recreation equipment, and amusement rides.

Professor Eager, what is your background and expertise?

My undergraduate degree is in mechanical engineering. However, over time my focus has shifted into bio-mechanical, looking specifically at human movement by measuring and assessing G-forces on the human body. My research is very closely linked to my roles on standards and advisory committees as well as expert witness and advisory roles. At Standards Australia, I have represented Engineers Australia on the playground Standards Committee since 1998 and more recently chaired this committee. I have been on several other standards committees, which usually come about after there have been incidents that call for a review of standards.

What does it mean to manage risk?

It’s about balancing the benefits of risk with the potential for nasty injuries that can occur. For example, in 1998 when I first got involved with the playground standards committee, playgrounds in Australia were incredibly boring and didn’t provide any excitement for kids. It was terrible. So, I made it my mission to put some fun back in playgrounds, while at the same time, engineering them so they were hazard free. There's an important distinction between a risk and a hazard. The hazard is the thing we want to get rid of, and the risk is the thing we manage.

I'm happy to have achieved that objective and we now have all these exciting playgrounds in Australia where we are managing the risk. This is wonderful because we know from experts in childhood development and psychology that risk is essential for childhood development in terms of decision-making, confidence, health, balance, and more.

There's an important distinction between a risk and a hazard. The hazard is the thing we want to get rid of, and the risk is the thing we manage.

Professor David Eager

There have been no deaths attributed to playgrounds on my watch, and I'm really proud of that. We do get injuries such as broken bones; however the threshold that’s recognized all around the world is no deaths and no serious permanent injuries, and we're pretty good with that in Australia.

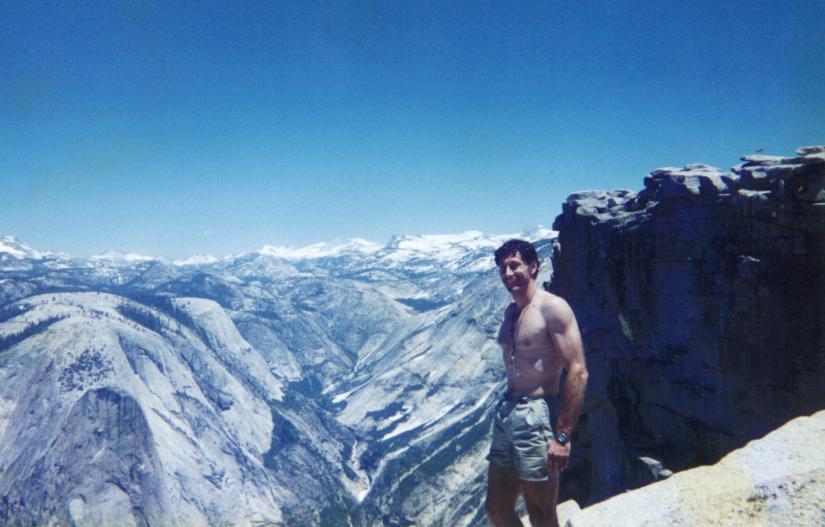

Professor Eager's interest in adventure spans his professional and personal life. In 1997 he climbed the Half Dome at Yosemite National Park, USA. Photo: supplied.

What formative experiences shaped your career?

I first undertook an undergraduate degree at UTS, though it was called the NSW Institute of Technology (NSWIT) at that time. The structure was an 18-week semester, and then we were employed in the industry for the rest of the year. So, I joined the Reserve Army and was in 1 Commando Company. This really gave me a love of risk, adventure and working in small interdependent teams. It was difficult juggling study, work and the army reserve, but I managed and graduated with first class honours – even though I fell asleep in a final exam due to sleep deprivation after a rather gruelling weekend exercise! I also started the mountaineering society at NSWIT, so my interest in risk and adventure crosses both my professional and personal life.

After graduation, I worked in various roles across mining and construction and then I had a really nasty car accident where I got t-boned heading to a meeting, and I almost died. It was one of those crossroad moments in life where I really stopped and thought about what was important, and that there must be something better.

It was one of those crossroad moments in life where I really stopped and thought about what was important, and that there must be something better.

Professor David Eager

It just so happened that my favourite lecturer from undergraduate days had an Australian Postgraduate Award scholarship available. I applied and was successful. So, I went down to the Australian Defence Force Academy to do my PhD. Then, just as I had almost completed, a 50% shared lecturer position came up at UTS, and I was successful. Then three months later I was appointed as the Director of the Bachelor of Technology Programs reporting directly to the Dean. The program was initially only manufacturing; however, the following year was expanded to include aerospace operations, and heating, ventilation and air conditioning. I have now been working at UTS for 27 years!

What excites you about the research you do?

Saving people's lives and reducing the frequency and severity of injuries excites me. I don't want anyone to go to the hospital. So, writing standards that eliminate the cause of injury excites me, and I know that sounds boring, but it does!

What have you learned in your research that you’d like more people to understand?

Parents often want to help their nervous child by accompanying them on a slide or trampoline, but letting the child take risks alone is infinitely safer.

For instance, when a parent gets on a trampoline with their toddler, the parent is much heavier than the child and there's this accident that happens in which the momentum of the heavier person is transferred to the lighter person. It’s called double bounce.

The double bounce is very dangerous. From a bio-mechanical engineering point of view, this transfer of momentum means the G-forces that the child can get are huge, and it can snap their legs or spine in less than a heartbeat, and then they're in a wheelchair for the rest of their life. The sad thing is that parents often don’t know that simply bouncing with their child on a trampoline like this can cause such a horrific accident. My research team have just had a paper published looking at what happens when older children do this with one another, which can also be very dangerous.

The sad thing is that parents often don’t know that simply bouncing with their child on a trampoline like this can cause such a horrific accident.

Professor David Eager

How has your research informed your teaching?

My research and expert opinion work has always translated into great teaching material. When I taught the subject Risk management for engineers, I could wander into a lecture room and literally tell them about what not to do as an engineer because I was regularly coming across some poor engineer’s mess up! What we want to do as engineers is learn from other people's mistakes rather than our own wherever possible, and we definitely want to make sure it doesn't happen again.

I tell students it's very difficult being an engineer, because if we get it right, nobody knows. It’s only when we make a mistake that people notice. When things break or fall down, people die or get injured because someone hasn't done their job and you do not want that person to be you.

What have been some of the most rewarding achievements in your career?

I’m very pleased with the work I’ve done with improving playgrounds. I was also a UTS student ombud for nine years. The forensic skills that I developed assessing engineering failures meant I was really suited to the role. There were several particularly difficult cases. For example, there was one student with Crohn's disease, who had really had a hard time navigating the system. And she was only two subjects from completing. She’d worked really hard to get that far with her illness, but the rules were just so rigid. As ombud I was able to work with staff from her faculty and student services to develop alternative assessment tasks and get her over the line to graduation. Over that time there were many cases like this, and it was really meaningful to be able to help those students.

I tell students it's very difficult being an engineer, because if we get it right, nobody knows. It’s only when we make a mistake that people notice.

Professor David Eager

What’s next?

There’s a lot of things. I’m just starting on is a project looking at the question of whether it is possible to reduce falls in older people by measuring jerk. Jerk is the rate of change of acceleration, and it’s a good predictor of instability prior to an actual fall. There is already some research that shows that when workers are fatigued their motion becomes jerky. What I want to investigate is if the same is true for the elderly. So, the idea is that we will put an accelerometer on a participant and see if it can predict when a fall is likely, so that there may be time for an intervention to prevent the injury before it happens.

Professor Eager (right) with his son, Lucas in 2006 at Mount Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. Photo: supplied.

27 years is a long time, you must have seen a lot of change in attitudes and behaviours over that time.

Absolutely. For four years I represented Engineers Australia on the Australian Standards Committee EV-015 Greenhouse gas measurement and accounting. I resigned from this committee when the Howard government effectively stripped the Australian Greenhouse Office of its powers.

While I was on EV-015, I was asked to create an environmental engineering subject at UTS called Air and Noise Pollution. I taught and coordinated this subject from 2003 to 2017. I remember asking the 2003 class "who believes in global warming?" There was only one student who sheepishly raised her hand. In 2017, nobody raised their hand when I asked, "who doesn’t believe in climate change?". Despite the glacial pace, we have travelled far.