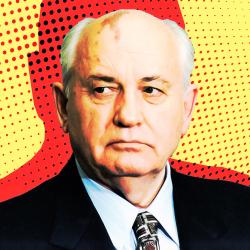

Russian leadership at its best

The death of Mikhail Gorbachev at the age of 91 is profoundly sad. It reminds me of how much better Russia can be.

Gorbachev was young at 54 when he became General Secretary of the Communist Party in 1985, bursting with energy and a conviction that the USSR could be a better place for its people and the world. Before him, in quick succession between 1982 and 1985, three leaders had died – Breshnev, Andropov and Chernenko, all ailing, old and committed to a system that didn’t work and that they didn’t want to change. Gorbachev did want to change his country, made up of 15 mostly culturally different republics, a moribund economy, vast and deep corruption, and locked in a hopeless war of words and military one-upmanship with the west. Homo Sovieticus to his bootstraps, he certainly didn’t want the USSR to collapse, but he did want his people to be ambitious for a better life. And he moved fast: he created a new parliament called the Congress of People’s Deputies and allowed its proceedings to be broadcast live on television every day, which resulted in a notable slump in productivity as people skived off work to watch. People were shocked too when new television current affairs shows began questioning their political leaders, and when Gorbachev refused to stop the Warsaw Pact countries leaving the fold and presided over the reunification of Germany.

Gorbachev, as history knows, changed his people but not the Communist Party. By August 1991, the party had had enough. During the three days Gorbachev was held under house arrest in Crimea, the party sent tanks onto the streets of Moscow to restore ‘order’, and for me as a Moscow-based correspondent covering it all, it seemed equally impossible to imagine how the USSR could survive or that it might collapse. Gorbachev clearly couldn’t imagine it collapsing either. I watched from the front row of a media conference as he told the world, when he was freed from house arrest, that socialism was alive and could still lead the Soviet people to nirvana. He would regret saying that.

Years later we met in Sydney. Though I had been in his orbit in Moscow as a journalist, even the 30 minutes he offered was a bonus given I had written a book on the USSR’s collapse. In the end, we spoke for many hours (he did love to talk) during which he said he never considered calling in the military to salvage the USSR, after three former republics (Russia, Ukraine and Belorussia) signed the USSR’s death warrant. Too many people would have died, he said. Mikhail Gorbachev hadn’t forgotten the lives lost in the Baltic uprisings or at home on Russian soil during the tumultuous years leading to the coup attempt. He saw himself as a peacemaker. He knew he had failed but saw merit in this failure.

Though many Russians whose lives were upended when the USSR collapsed would disagree, the last leader of the USSR – the man who refused to stop the Soviet empire falling apart – should remind the world what Russian leadership is at its best.

Monica Attard, CMT Co-Director

This article was featured in our newsletter of 2 September 2022, read it in full here.

To subscribe and stay up to date with all things Centre for Media Transition, click here.