Three-stage economic recovery a significant challenge

Frydenberg's three-stage economic recovery is abominably hard to get right.

Gone are the days when economic policy was adjusted once each year by the government in the budget and fine-tuned once each month at meetings of the Reserve Bank board.

The coroanvirus means we haven’t had a budget in more than a year. What the Reserve Bank has done to interest rates means its monthly board meetings matter less.

Governor Philip Lowe reaffirmed this week that monetary policy was on hold for the foreseeable future. The bank’s cash rate is as low as it can go (actually well below its 0.25% target) and the bank will only intervene in the bond market if it has to in order to keep bond rates low (which it doesn’t — the demand for even the rush of new bond issues is much bigger than the supply).

It has lobbed the ball to Frydenberg’s side of the court.

The only situation in which it might be brought back into play is if the government ran into funding problems, of which there is no sign whatsoever.

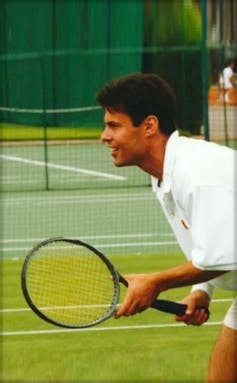

Holding the racket

Credit: Josh Frydenberg.

The treasurer’s problem is sequencing, and we will are likely to get hints on how he’ll play it in the economic statement to be released today.

The first challenge was to limit the damage to the economy from the initial shock near the start of the year — to stop a vicious cycle of weaker spending, plummeting investment and soaring unemployment.

These self-reinforcing crises required a circuit breaker.

The emergency stimulus provided through Jobkeeper and Jobseeker has been a great success at putting a floor under incomes and demand.

The government ensured a basic income for people whose jobs were axed or at risk, kept hundreds of thousands attached to their jobs and bolstered household incomes despite a massive loss of activity. It gets a tick.

But these emergency measures will not get the economy going again once the crisis has eased.

Some argue they will stand in the way of a recovery if they keep people ensconced on benefits or attached to firms without futures.

A tricky transition

Phase two will require genuine fiscal stimulus: not a security blanket of the kind we have had, but a direct injection of money that will spark a new wave of investment and employment.

The trick is to sequence it properly.

The announced tapering of JobKeeper and JobSeeker will cut incomes and cut jobs as firms pay people less and realign staff levels in line with lower subsidies.

The government believes it has got it right, but it is forecasting an 80% drop in JobKeeper payments between September and the end of the year. It might not be a cliff but it is still a very steep slope that will need to be matched by a sharp recovery in economic activity.

It needs to be ready to revise the timetable as needed. Its current projections look like a best case scenario.

An unknowable stage two

The second stage will involve a good deal of spending on infrastructure. But, especially without certainty about immigration, it is hard to tell what will be needed.

The pandemic will have changed the way we work and play. It is not yet clear whether people take advantage of remote working and move out of congested cities. it is not yet clear what it will mean for digital health, digital education and digital shopping.

An even-harder stage three

The final stage will involve structural reforms; alterations to tax settings, regulations and industrial relations. Which is where it gets really hard. It will require not only sequencing but getting agreement across the political divide.

No civil society can base its economic and social structures on the mere desire for efficiency. Fairness and social justice matter just as much, and they can best be guaranteed if the measures are pulled together as a package with trade-offs that protect the values that matter to Australians.

That’ll be Frydenberg’s biggest challenge. The future doesn’t need to be rushed out this week, or in the October Budget, but in the months to come it’ll have to take shape.

Read more: These budget numbers are shocking, and there are worse ones in store ![]()

Warren Hogan, Industry Professor, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.