Addressing Child and maternal health – PNG

The WHO CC UTS acknowledges use of key language from The WHO Global Strategic Directions for Nursing and Midwifery (2021–2025).

Midwives who are well trained and educated to international standards are able to deliver 87% of the care needed for newborns and mothers globally [1]. Collecting accurate data around child and maternal health in PNG has been a challenging task - some sources quote the MMR as 733 per 100,00 and some quote 170 per 100, 000 [2, 3]. In spite of this discrepancy, PNG is commonly regarded as having the highest rate of infant and maternal deaths in the Western Pacific Region.

Research has shown that the most significant, cheapest and simplest way to address the IMMR (Infant Maternal Mortality Ratio) is through employing more highly qualified midwives [4]. A report conducted between 2011-2013 revealed that increasing the number of midwives in low-income countries like PNG by 25% would reduce maternal deaths by a staggering 75% (UTS Report) [5].

In response to this, the government launched the national Maternal and Child Health Initiative (MCHI) in 2012. Several programs were combined and developed over the next decade aimed at systematically improving PNG’s maternal and child health outcomes and expanding the midwifery workforce [6].

A governmental review led to the PNG National Framework for Midwifery Education. This looked at curriculum development and health system capacity building, strengthening regulation, accreditation and establishing midwifery registration [7].

Over the course of the next decade, the PNG Department of Health worked with WHO CC UTS to build the midwifery capacity in the country [8]. The number of midwifery schools was increased from 4 to 5, 11 international clinical midwifery facilitators were embedded in the schools to mentor the students and provide teaching resources for PNG educators and a standard curriculum and accreditation process was introduced in all PNG midwifery schools. One key change was upgrading the curriculum from a 12 month to an 18month program to ensure that midwives had adequate skills to meet maternal and child health needs of the country. This program was a true partnership between Australian and PNG midwives and many reviews and joint papers were published.

Registrar of the PNG Nursing Council, Dr Nina Joseph, reports directly to the Ministry of Health and has been working to improve midwifery regulation. Her work has been key to developing an audit and accreditation system for PNG and prior to her work, an audit of PNG’s nursing and midwifery capacity had not been carried out in over 30 years. Dr Joseph’s PhD project looked at ways to improve midwifery services in PNG.

Dr Joseph emphasises why we still need to continue to strengthen midwifery education in PNG because

population is increasing rapidly. With more births and more pregnancies, the likelihood of complications also increases. So, it’s vital we have more highly skilled midwives to save lives. In a nutshell, education is vital to saving babies and reducing the country’s MMR. Education is really the way forward.

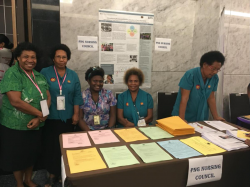

As a result of the MCHI, over 400 midwives were educated and registered from 2012-2016, doubling the existing workforce numbers. Many of these graduates had been placed in rural and remote areas that had a lack of health care services and two international obstetricians were placed in regional hospitals. The revitalisation of the profession saw the re-establishment of the PNG Midwifery Society with support from the MCHI midwifery facilitators and their first national conference was held in 2015 which attracted more than 300 midwives across the country.

While the discrepancies in health care data in PNG makes it challenging to quantify the changes in the MMR in PNG, according to PNG obstetricians, the MCHI initiative has had an extremely positive impact on maternal and infant health across the country. Most health centres in the country are now staffed by a qualified midwife and there’s an increased focus on women-centred care, improved outcomes and women’s experiences. A UTS-led evaluation of the MCHI found substantial improvements in the quality of clinical education on offer with a stronger focus on evidence-based skills.

However, as Joseph stressed, this is still not enough,

we have 1500-2000 women dying every year. Something needs to be done to address this. Compared to other Pacific countries, the country is in no way near the average number of midwives needed.

[1] Rumsey, M., N. Joseph, and M. Kililo, The need for improved educational development of nurses and midwives to strengthen quality of care in PNG - 10 year Review., in ANU Policy Development PNG Update,. 2019, WHO Collaborating Centre, University of Technology Sydney: Papua New Guinea,.

[2] Radio New Zealand. Maternal mortality rate rising in PNG. Pacific Papua New Guinea 2018 1 June 2018 [cited 2020 1 February ]; Available from: https://www.rnz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/358647/maternal-mortality-rate-rising-in-png.

[3] WHO. Country Profile Papua New Guinea. 2014 [cited 2016 08 December].

[4] Organization, W.H., Newborns: reducing mortality. 2019, WHO.

[5] Thiessen, J., M. Rumsey, and C. Homer. Papua New Guinea Reproductive Health Training Unit (RHTU): Monitoring and evaluation final report. 2017; Available from: http://dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/Pages/png-reproductive-health-training-unit-monitoring-evaluation-report.aspx.

[6] Rumsey, M., Helping build foundations for improved maternal health in PNG , in 10th Conference OF the global network of the WHO collaborative Centres for nursing and midwifery. 2014, WHO CC UTS: Coimbra in Portugal.

[7] Rumsey, M., Helping build foundations for improved maternal health in PNG, in 10th Conference OF the global network of the WHO collaborative Centres for nursing and midwifery 2014, WHO CC UTS: Coimbra in Portugal.

[8] Neill, A. and Rumsey, M. PNG Maternal and Child Health Initiative Phase II: Mid-term Summary Report. 2015, World Health Organization Western Pacific Region, AusAID & PNG National Department of Health: Sydney, Australia.