New study examines impact of major life events on wellbeing

Researchers have compared the differing impacts of 18 major life events on the happiness and life satisfaction of Australians, and how long the impact lasts.

Image: Shutterstock

Major life events such as marriage, death of a loved one or bankruptcy all affect our wellbeing. Now, for the first time, researchers have compared the differing impact of these events on the happiness and life satisfaction of Australians, and how long that impact lasts.

The study examined 18 major life events, and how they affected a sample of 14,000 Australians between 2002 and 2016. The data was taken from the HILDA survey, which examines the social, health and economic conditions of Australian households using face-to-face interviews and self-completion questionnaires.

The study: The differential impact of major life events on cognitive and affective wellbeing, was recently published in the journal ‘SSM - Population Health’ with co-authors from the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) and the University of Sydney.

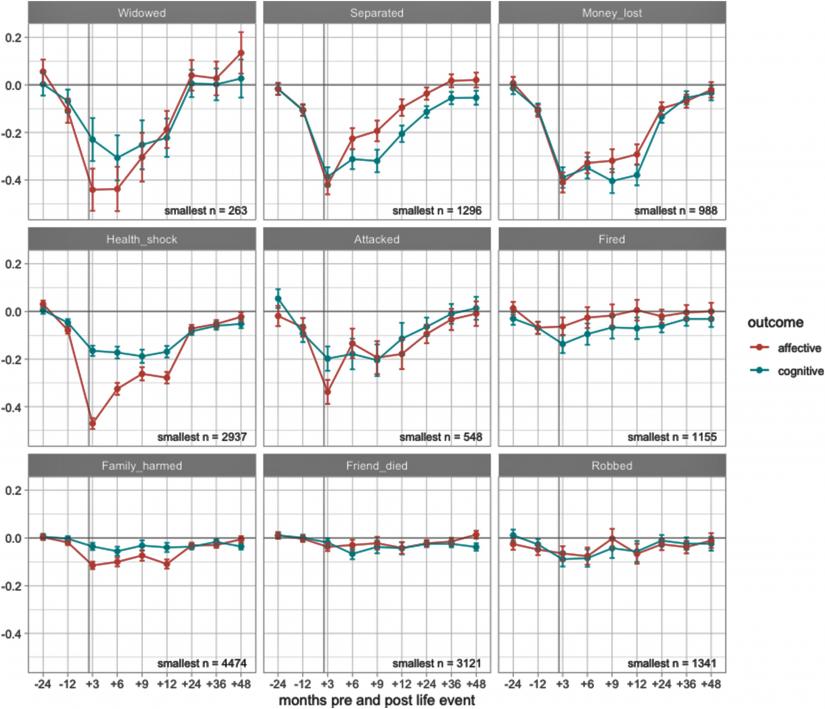

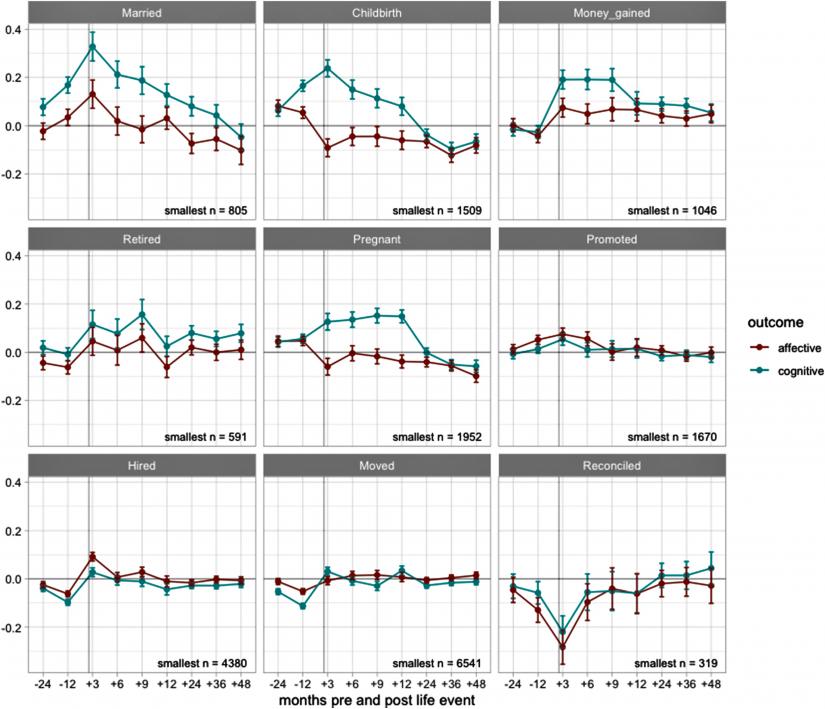

The results show that some events, such as moving house, getting fired or getting a promotion, had little impact on wellbeing, while others, such as the death of a partner or a large financial loss, had profound impacts.

“Marriage, childbirth and a major financial gain produced the greatest elevation to wellbeing, however they did not lead to long-lasting happiness – the positive effect generally wore off after two years. However, there was also an anticipatory effect for marriage and childbirth, with wellbeing increasing prior to these events,” says lead researcher, UTS economist Dr Nathan Kettlewell.

“The life events that saw the deepest plunge in wellbeing were the death of a partner or child, separation, a large financial loss or a health shock. But even for these negative experiences, on average people recovered to their pre-shock level of wellbeing by around four years,” he says.

A greater understanding how life events impact wellbeing, and how long it takes to adapt, can help government and policy makers better target resources to improve the happiness and welfare of society.

The graph above shows the effect of each life event on cognitive (red) and affective (blue) wellbeing from two years before the event to four years after the event, ignoring any concurrent life events.

“A growing number of countries, including the UK, Iceland and New Zealand, as well as the OECD, are measuring wellbeing, alongside economic growth, as a way to gauge success in improving the lives of citizens,” Dr Kettlewell says.

“Information on wellbeing also helps clinicians and healthcare professionals better understand the repercussions of major life crises such as the death of a loved one, a health shock or job loss.”

The researchers examined two different types of wellbeing.

The first was ‘affective’ wellbeing, which reflected ‘happiness’ or the frequency and intensity of positive or negative emotions. The second was ‘cognitive’ wellbeing, which refers to a more deliberate, goal-directed evaluation of ‘life satisfaction’.

While some life events such as marriage and retirement had positive effects on ‘cognitive’ wellbeing, the net effect of positive events on ‘affective’ wellbeing was close to zero.

Pregnancy and childbirth in particular saw the largest gap between the two domains. Measures of ‘life satisfaction’ were quite positive in the first year after the birth of a child, while happiness or emotional wellbeing actually declined during this time.

The researchers also accounted for how life events often occur together, for example divorce and financial loss, to tease out the differing impacts.

The four most common life events were moving house, finding a new job, a serious injury or illness in a close family member and pregnancy. The least frequent were becoming widowed and getting married.

“While chasing after happiness may be misplaced, the results suggest that the best chances for enhancing wellbeing may lie in protecting against negative shocks, for example by establishing strong relationships, investing in good health and managing financial risks,” says Dr Kettlewell.

“And we can take consolation from the fact that, although it takes time, wellbeing can recover from even the worst circumstances.”

The graph above shows the effect of each life event on cognitive (red) and affective (blue) wellbeing from two years before the event to four years after the event, ignoring any concurrent life events.