What COVID-19 means for the people making your clothes

COVID-19 has been disastrous for people who make our clothes, but there are small signs of hope.

Shutterstock

Workers everywhere are feeling the impact of COVID-19 and the restrictions necessitated by COVID-19.

In Australia, retail and hospitality workers have been particularly hard hit. In other countries, it’s manufacturing workers, hit by disruptions to value and supply chains.

A value chain is the process by which businesses start with raw materials and add value to them through manufacturing and other processes to create a finished product.

A supply chain is the steps taken to get a product to a consumer.

Most of the time we don’t think about them at all.

Cotton is complex

Our research project with the Cotton Research Development Corporation is investigating strategies for improving labour conditions in the value chain for Australian cotton.

This is the chain in which our cotton is spun into yarn, woven or knitted into fabric, and turned into garments and other items which are sold to consumers.

When we began our project in mid-2019 the world was a very different place.

The changes brought by COVID-19 have had a significant impact on those working throughout the chain – particularly in garment production, but with flow on effects to other tiers.

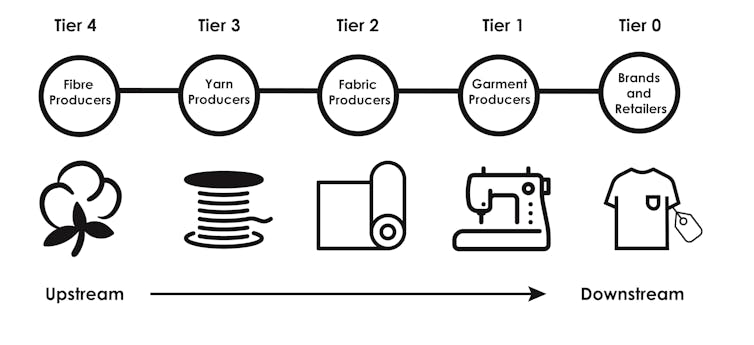

The tiers in the diagram are numbered backwards.

The first is Tier 4, where Australian cotton is grown and harvested. The next is Tier 3 where it is turned into yarn, usually overseas.

Tier 2 is the production of fabric, Tier 1 is the production of garments and other products, and Tier 0 is retailing and selling to retailers.

Alice Payne

Tier 0 (brands and retailers) has been hit by delays in shipments due to factory closures at Tiers 1 and 2.

However this has been matched by a decline in demand as social distancing and lock-down arrangements discourage or prevent consumers from shopping in person.

In Australia retailers such as Country Road, Cotton On and RM William temporarily closed, taking short-term retail job losses to 50,000 or more.

Globally, many multinationals have closed their doors.

Shocks along the chain…

Nike is expecting sales to drop by US$3.5 billion. While seemingly immune from some of the social distancing provisions, online retail is also likely to take a hit due to a drop in demand.

Tier 1 (garment manufacturing) has been hit by falling demand as retailers cancel orders or ask for delays in payment. It has also faced disruptions in the supply of fabric, especially from China.

Fabric producers in Tier 2 and cotton spinners in Tier 3 have had to contend with a decreased supply of raw materials and demands to retool to produce medical equipment.

For cotton growers in Tier 4, the fall in demand has pushed prices down from US 70 cents at the start of the year to US 50 cents, the lowest price in a decade, before a partial recovery to US 58 cents.

…with human costs

Reports of losses of tens of thousands of jobs in Myanmar and Cambodia paint a bleak picture.

In Bangladesh estimates have 1.92 million workers at risk of losing their jobs as factories receive notice of US$2.58 billion worth of export orders cancelled or on-hold.

Making things worse, many workers in Tiers 1-3 were receiving less than a living wage defined as the minimum needed to provide adequate shelter, food and necessities. This has made it hard for them to plan or save for emergencies.

Many are migrant workers without funds to return home.

Even the workers who manage to hang on to their jobs aren’t in the clear. Programs set up to improve their working conditions have been disrupted.

The Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh is a legally-binding agreement between brands and unions set up in the wake of the collapse of the the Rana Plaza factory in 2013 which killed 1,133 people and critically injuring thousands more.

Inspections under the program have been suspended, as have audits due to the closure of borders.

The problems are cumulative – delays in orders due to interruptions in supplies will need to be addressed when factories scale back up, creating demands from buyers that might result in pressure for workers to work unpaid and involuntary overtime, or even worse, subcontract to the informal market where there is a high risk of human rights violations.

Shoots of hope

Amid the havoc are some shoots of hope.

Companies along the value chain have been asked to produce and supply medical equipment such as surgical gowns, face masks and materials and elastics.

Dozens of brands and retailers have donated funds and activated their logistics networks to support the effort.

As orders slowly start returning, cotton and textile associations have joined forces in calling for greater collaboration throughout the value chain. Governments have announced aid packages for their workers, and the European Union has provided an emergency fund to support the most vulnerable garment workers in Myanmar.

Longer term, the supply risks highlighted by the disruption might cause companies along the value chain to diversify their suppliers and even produce locally.

The crisis has demonstrated forcefully the importance for manufacturers and retailers to be agile. Yet this can best be done when workers have been well trained and have access to the best technology and equipment.

For now, we watch and see. Cotton is as good an indicator as any other of the brittleness of supply chains and the ways in which what we produce and consume affects the livelihoods of those further down the chain.

In the short-term, a best-case scenario would see a revaluing of garment work as “essential” in order to produce protective/medical equipment that we need in a way that benefits the people who help make them.![]()

Sarah Kaine, Associate Professor UTS Centre for Business and Social Innovation, University of Technology Sydney; Alice Payne, Associate Professor in Fashion, Queensland University of Technology, Queensland University of Technology, and Justine Coneybeer, Research Assistant - Supply Chain, Queensland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.