Lessons for COVID-19 from LGBTIQA+ communities

New social and political environments created by COVID-19 would have been hard to imagine three months ago. We are all still coming to terms with extreme measures to minimise harm and risk.

Although this climate is unique, it is worth taking a moment to reflect on the parallels with another pandemic. LGBTIQA+ communities who struggled and dealt with the HIV/AIDS crisis have lessons to share on how we can weather this storm.

To date, the HIV/AIDS epidemic has infected 75 million people and killed 32 million. It has been the source of untold human tragedy, causing longstanding stigma. Many see analogies with COVID-19 in governments’ failure in rapid action, and stigma directed at specific groups. But we are also seeing pockets of heroism and the best of human nature.

Experiences from LGBTIQA+ communities’ response to the AIDS crisis show us that fighting an epidemic through community care, political action, and mutual aid can help reconcile the human consequences and turn crisis into action.

Community care

LGBTIQA+ communities faced, and continue to face, severe marginalisation, along with extremely high rates of mental health diagnosis. Adding to this, the health response to HIV/AIDS was cruel and dehumanising for a long time.

In the face of structural oppression, individuals formed connections, created their own communities, and pioneered comprehensive community models of care and advocacy.

Key organisations quickly built up through strong and active community organising. Two years into the AIDS epidemic starting in the United States, 45 self-help groups had been formed. By the end of the first decade of the epidemic, more than 600 community-based organisations that provided services for AIDS-affected people had been created around the country.

This wasn’t limited to the US; Australia’s ACON was established in 1985, “defined by community coming together to respond to the HIV/AIDS epidemic in NSW”, as stated on their website. The decade also saw AIDS Action Committees formed in Sydney and Melbourne, and the Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations established.

Volunteers across the world provided assistance, food, staffed hotlines, and provided support to build resilience through community. The community groups that built up around these needs then formed a base for advocacy and political organising.

Political action

Populations of LGBTIQA+, in particular gay men, became extremely politically active in the 1980s. The organisations formed during this time continue to advocate for LGBTIQA+ populations affected by HIV.

Groups in America campaigned for universal access to healthcare. Their community advocacy during the peak AIDS epidemic years succeeded in convincing San Francisco to invest a huge amount of resources and a public health response. In Australia, campaigns launched to shift the focus away from HIV/AIDS as a morality issue – at a time when the emotional and sexual lives of gay men were illegal – to a public health issue.

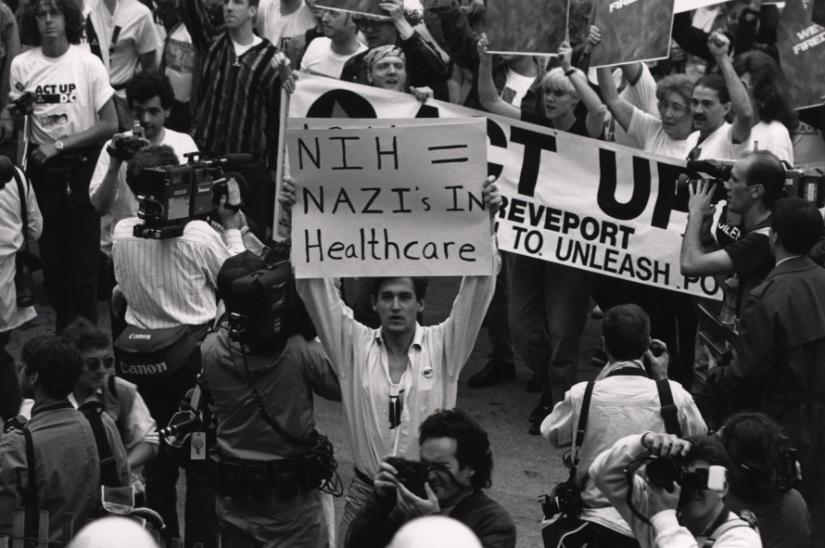

ACT UP Activists at the National Institutes of Health in the United States.

In a paper released by the National Association of people with HIV Australia, Bill Bowtell, a gay man and policy advisor who was a senior advisor to the Australian Health Minister in the 1980s, said:

“Thanks to the visionary activism of those in the early days of AIDS, and the profound insights of those living with HIV, many thousands of young people were saved from infection, and the lives of positive people transformed by the earliest possible access to effective treatments. And, very importantly, a new model for dealing with other diseases was created, and shown to work outstandingly well. It is a legacy of which we can all be proud.”

Activism brought attention to systemic injustice, united communities in a collective voice for change and educating against discrimination. It has shaped institutional responses to health including issues from bodily autonomy to harm minimisation for drug use.

Where a crisis highlights systemic injustice, it can provoke a sustained community response that has potential to impact political agendas. COVID-19 is revealing terrible vulnerabilities around job security, the welfare system, and prioritisation of healthcare. The impacts of this time will stay with people long after the virus has abated.

Mutual aid

The main role of the community organising that mobilised during the HIV/AIDS outbreak in the 1980s was creating networks of community care for HIV affected people. Volunteers shouldered a significant share of caring for patients and providing necessary services outside of the official healthcare system.

In the face of severe restrictions on movement to stop the spread of COVID-19, we see cracks emerging in the way we have organised societies.

Necessary social distancing and self-isolation is much easier to achieve if you have material resources and family members willing and able to help. Not everyone has access to those resources. We need the community to step up to provide social and material support for those who are being affected most. The social distancing project is being viewed as a social and community responsibility.

What was true for LGBTIQA+ communities in the 1980s is true for COVID—19 too, as countless mutual aid groups are popping up. People are checking in on their elderly neighbours, their colleagues. They are donating masks and protective equipment, cooking hot meals for healthcare workers, and coming up with creative ways to connect and socialise. We are seeing a broad community response.

As in many extreme situations, pandemics past and present have brought out the extremes of human behaviour. We’ve seen the best and the worst of human nature.

As we adapt to this new situation, let’s makes sure that human kindness is still a mainstay of our new normal, and the lessons we learn may spark action for long-term social and political solutions.