Design ideas that start as a trickle, become a torrent

Rushcutters Creek was once a trickling waterway that ran from Paddington’s Trumper Park down to Rushcutters Bay. Today, the creek runs largely underground and through a graffiti-ridden stormwater channel before making its way to the sea.

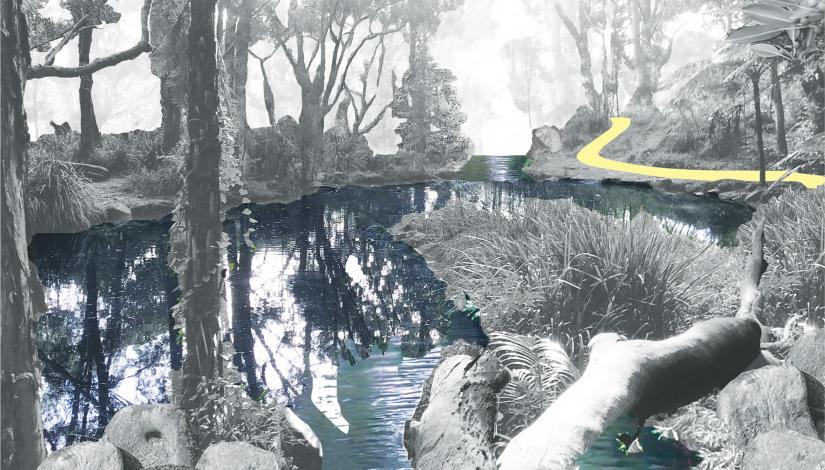

Section of Rushcutter's Creek perspective render by UTS Landscape Architecture student, Christina Kirkwood.

It may sound uninspiring, but for students in the UTS Bachelor of Landscape Architecture, the creek represented an untapped opportunity. In the Landscape Architecture Studio 3 subject led by lecturer Saskia Schut, the students were challenged to revive the waterway and create a publicly accessible green space where locals and visitors could connect with the natural environment.

“We did a lot of classes down at the site where we walked the creek’s original route. We did activities where we would sit down and record the sensory interactions we had with the water and think about how we could improve it through landscape strategies,” says student Christina Kirkwood.

With the creek itself being the central focus of the work, students were encouraged to build their proposals around connections to water. Kirkwood created a model of the creek route based on contour maps of the area, pouring hot wax over the model to mimic how and where the water might have flowed before development intruded upon it.

“I was trying to look at the natural route that it would take through the land if human intervention was stopping it and blocking it and making it into a straight canal,” she says.

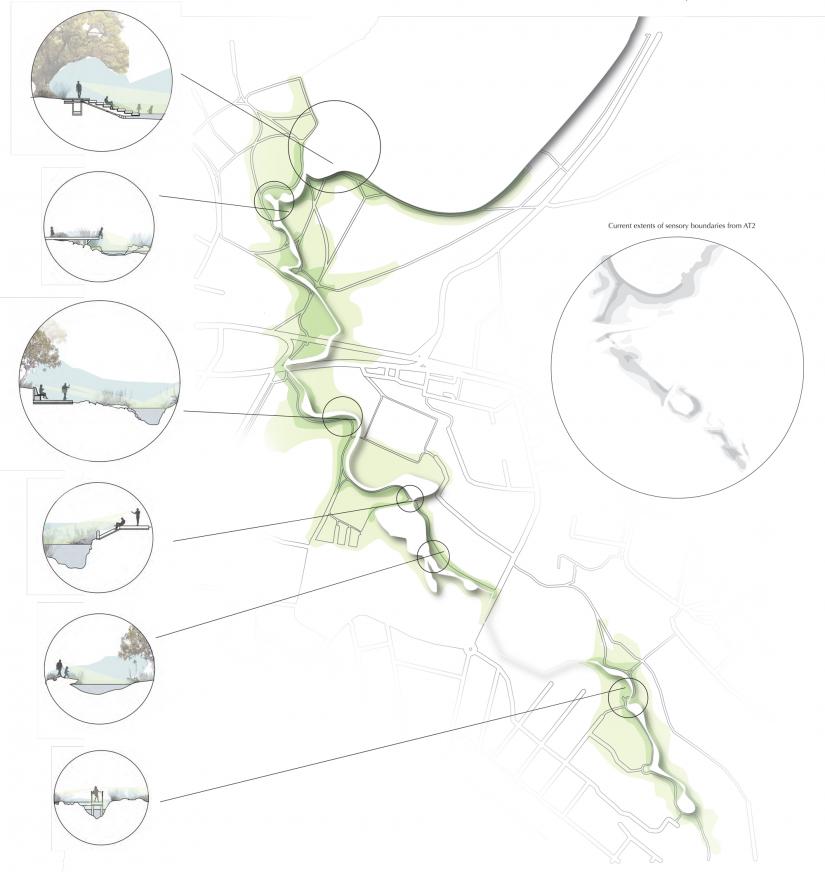

Christina Kirkwood's design re-routes surrounding pathways to encourage interaction with the creek.

Her subsequent proposal was an inner-city oasis that balanced the needs of urban development with the natural flow of the creek. The creek would be freed from its current culvert and allowed to flow freely, but would do so around important local urban features, such as the Rushcutters Bay sportsground.

A series of plants along the creek bed would reintroduce the namesake rushes of Rushcutters Bay, while other wetland plants would filter the water and improve the sensory experience of the creek for visitors.

Fergus Barker, another landscape student, took a different approach entirely. His plan was to split the stormwater channel down the middle and create two opposing spaces: one that amplified the idea of human presence, and one that removed it.

On the human side, the concrete of the stormwater channel would be retained, while on the ‘re-natured’ side, the creek and surrounding landscape would be left to grow wild. Wetland plant systems planted at different heights along the banks would also be introduced to help improve the water quality.

Students were tasked with recording their sensory interactions with the creek and improve it through landscape strategies. Photo: Fergus Barker.

“I wanted to introduce a sort of wetland system up near the harbour,” Barker says.

“The creek itself isn’t the cleanest at the moment – it’s stormwater, and when you get storms, it’s a flood zone, so it goes from this little trickle to absolutely rushing along.

“By introducing these wetlands, it would slow the speed of the water down and also help to clean the water going out to sea.”

Kirkwood and Fergus’s design concepts were originally created as part of their subject assessment, but they quickly took on a life of their own: both students were invited to present their projects both to Woollahra Council and the neighbouring City of Sydney Council, within whose boundaries much of the creek’s route falls.

If this gets built, it could create a whole network of green spaces in Sydney’s eastern suburbs.

The response has been extremely positive; both councils are now considering opportunities for a collaborative project to regenerate the creek and surrounding environments, including establishing pedestrian and cycling pathways for public use. Kirkwood and Barker are likely to be involved in the design process if and when the project goes ahead.

“If this gets built, it could create a whole network of green spaces in Sydney’s eastern suburbs,” Kirkwood says.

“Even the proposed route that we’ve designed for this creates 3.5 kilometres of pathway distance that people can walk.”

Learn more about the UTS Bachelor of Landscape Architecture (Honours).