Iron ore dollars repurposed to keep the economy afloat

The budget points to weaker times ahead unless wages and spending pick up. Wes Mountain/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

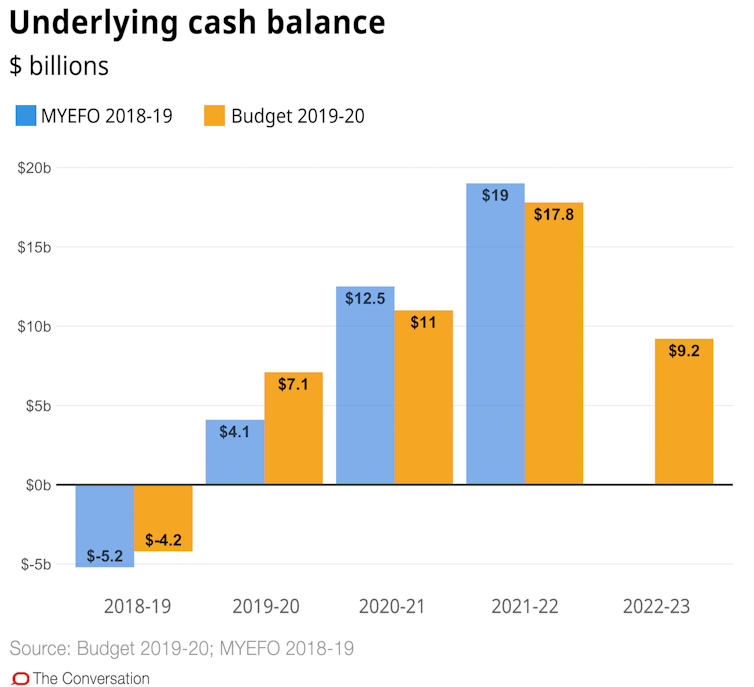

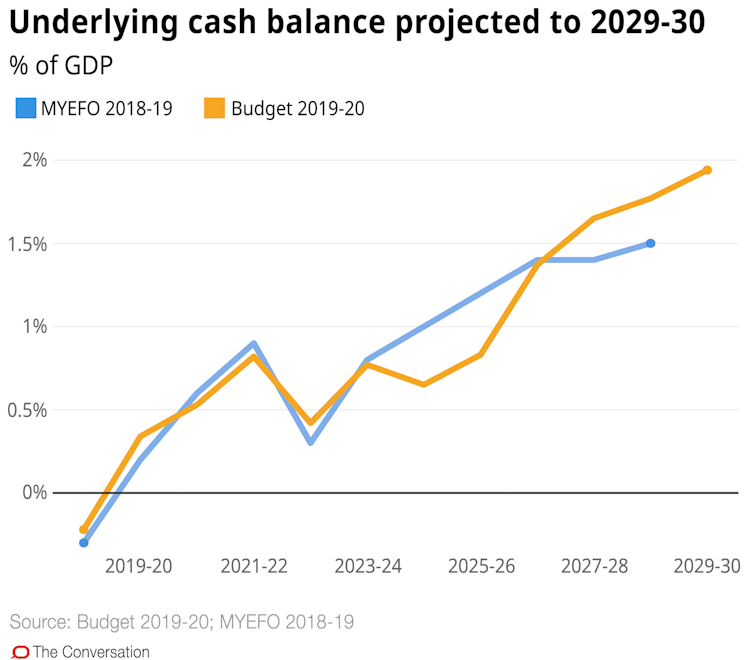

A weaker domestic economy has cost the budget A$15 billion over the next four years, but booming international commodity markets are more than offsetting this. The net result is a budget that will remain comfortably in surplus for the next four years, assuming the economic situation improves rather than disappoints.

Much lower payments on a range of different programs have also given the government some extra money to play with. Lower spending on the National Disability Insurance Scheme, a big drop in debt servicing costs and lower pension income support payments are just a few of the expenditure surprises that paint a very healthy picture of federal government finances right now.

But weaker domestic economic numbers have come at a considerable cost to the budget in an ominous warning about how vulnerable the government’s finances would be to a domestic economic recession.

Since the release of the mid-year economic outlook last December, economic data have generally disappointed expectations, culminating in a much-weaker-than-expected GDP report for the December quarter of 2018. This has forced the Treasury to reset the government’s baseline for the economy and its revenues.

This has been quite small in the scheme of things, with economic variables such as consumption, GDP and wages down by about 0.25% to 0.5% for this year and next.

Read more: View from The Hill: budget tax-upmanship as we head towards polling day

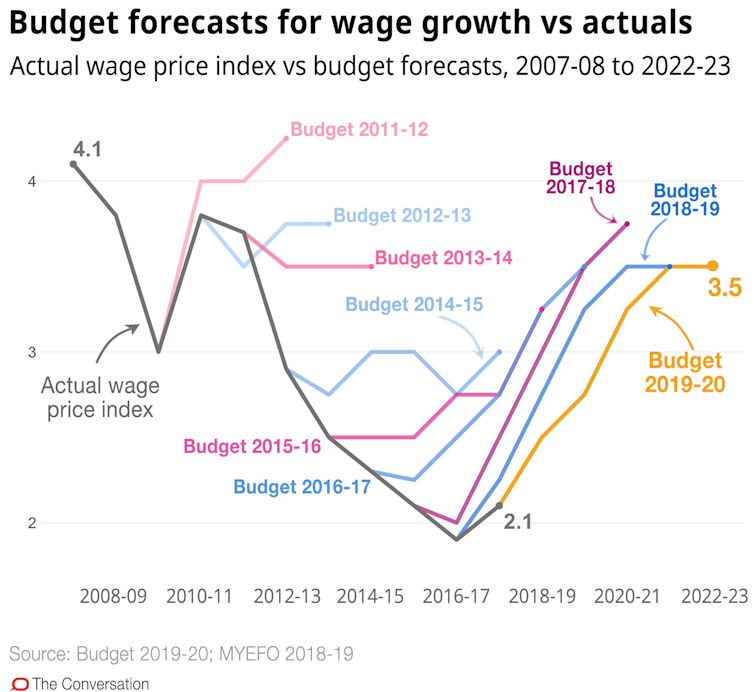

But these otherwise small changes to the economic baseline have had a big impact on government finances. Revisions to the outlook for wages have cost the budget $800 million in 2019-20 and a total of $8.1 billion over the four years to 2022-23.

Weaker-than-forecast consumption has knocked $1.7 billion out of GST receipts for 2019-20. It’s not a problem for the feds, but another sign that state government budgets are about to take a walloping over the next few years.

Economic story hasn’t changed, even if the starting point has

In terms of the picture the government is painting of the economy over the next three years, the economic forecasts are basically unchanged from those presented in the update in December. Sure, there have been some substantial downward revisions to the current year’s numbers and a knockdown in growth in 2019-20. But this is almost entirely the result of a weaker starting point courtesy of the soft GDP numbers we received last month.

The economic story hasn’t changed. Australia’s economy is set to ride out the bursting of the housing bubble in Sydney and Melbourne. Employment is expected to continue to grow at a pace that is strong enough to soak up new entrants into the labour force.

Meanwhile the international economy will maintain a healthy growth rate of 3.5% over the next few years. There is no US recession, no sudden shift down in China’s rate of growth.

The Treasury has adopted a pleasingly conservative approach to international commodity prices. Both met coal and iron ore are expected to drop back to more sustainable price levels over the next year in what is an important nod to good budgeting assumptions.

Iron ore is forecast to fall back to US$55 a tonne by March 2020 and then stay at that level while met coal is expected to shift back down to US$150 a tonne over the same time frame.

The oil price, interest rates and the Australian dollar are all forecast to stay at current levels over the forecast horizon. With bond yields having fallen to near-record lows in Australia in recent weeks, this assumption has had a dramatic effect on Australia’s debt service costs, delivering the government a financial windfall of $2.7 billion over the next four years.

Blue Skies or foggy glasses?

Against this backdrop Australia’s economic expansion is forecast to go well past the 30 -year mark in 2021. Unemployment is projected to be 5% and wages growth rises back to 3.5%.

This is a rosy picture of the economic outlook. The wage growth forecasts will rightly come in for some criticism. The risks to this forecast are not evenly balanced.

At least the government can’t be criticised for being at odds with the Reserve Bank (RBA). The RBA’s latest set of forecasts, released just a few weeks ago, are basically the same. If anything, the RBA is even more optimistic than the Treasury, with an unemployment forecast of 4.75% versus the government’s 5% for as far as the eye can see.

Even though the RBA and the Treasury seem to be on the same page about Australia’s economic outlook, there is now a clear distinction between what private and public sector forecasters are looking for over the next few years.

Over the past three months there has been a substantial shift in private sector forecasts for the economy, which has not been replicated by either the RBA or the Treasury.

This has left the RBA and the Treasury at the top of the range of forecasts for the economy. You’d be hard pressed to find a private sector forecaster more optimistic on Australia’s economic outlook than our policymakers are right now.

A short-term fiscal stimulus could keep the RBA at bay

The great fear within financial markets and across the business community is that Australia’s domestic economy could buckle under the weight of high household debt and falling house prices. A run of weak economic data in the last three months has added weight to these concerns and seen a number of economists call for interest rate cuts.

Even though businesses have thus far maintained a deal of optimism about the economic outlook, the concern is that eventually business will shelve hiring and investment plans if consumer demand weakens enough.

Money markets are factoring in a half-percentage-point cut to the cash rate, taking it from 1.5% to 1% over the next year. In effect, the markets are projecting much weaker outcomes than the RBA or the government.

This budget represents a smart short-term fiscal stimulus at a time when consumer sentiment and domestic demand are under pressure. This certainly should take some pressure off the RBA to cut interest rates in the next few months and may even keep monetary policy on hold for an extended period.

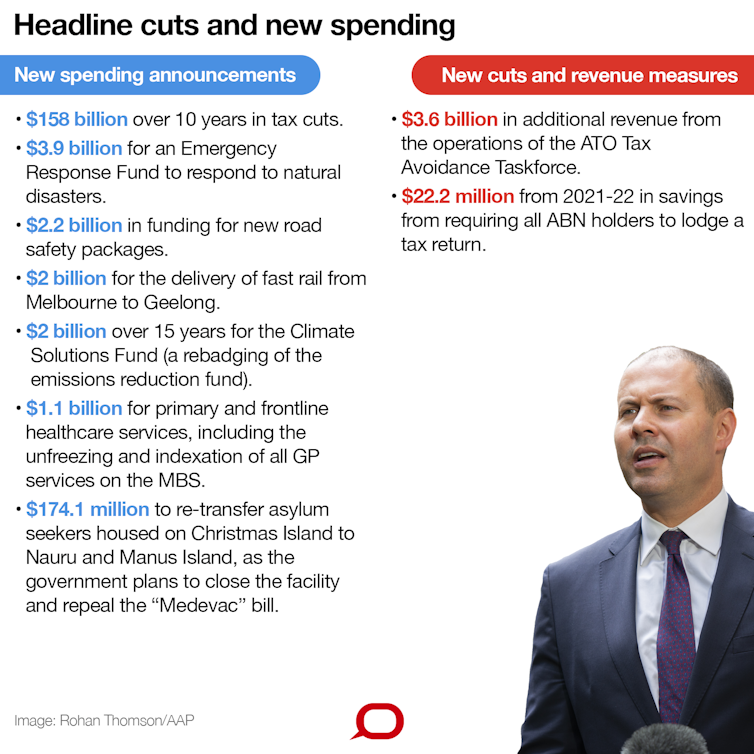

The centre piece of the fiscal injection is the lift in the Low and Middle Income Tax Offset (LMITO). This offset has more than doubled to $1,080 and is effective from this financial year. This means 4.5 million Australians will be positively impacted by a higher offset when they file their 2018-19 tax returns after July 1 2019.

This is as close to a cash handout as you can get without it being a cash handout – a cash handout by a government ideologically opposed to cash handouts.

This is not only a direct cash injection for many households but a retrospective tax cut in the sense that it dates back to July 1 2018.

People won’t have the extra money until after July, but they know it’s coming and this should immediately help alleviate some financial concerns.

The next leg of the immediate fiscal stimulus is the broadening of the instant asset write-off for small and medium businesses with revenue of up to $50 million. This was previously accessible to small business with revenues of up to $10 million. The asset write-off has been increased to $30,000 (from $25,000).

This too is effective immediately and will last through to June 2020. This is a strong incentive for a vast number of businesses around Australia to increase capital expenditure in the months ahead of the end of this financial year, and then again next financial year.

Even if it doesn’t have much impact on investment plans, it will impact profitability.

Longer-term personal income tax cuts that are happening against the backdrop of a budget that remains in surplus over the medium to long term also have the potential to support consumer confidence.

A strong government financial position will help curtail precautionary saving from households worried about the future of the economy and their finances.

For financial markets the question is whether this fiscal stimulus is enough to keep the RBA at bay over the months and years ahead. This fiscal injection is smart policy and represents a much nimbler government than we’re used to.

In an environment where the effectiveness of interest rate cuts is an open question, a short sharp fiscal injection like this one might make the difference in keeping demand at a rate that will maintain our current low rate of unemployment.![]()

Warren Hogan, Industry Professor, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.