The long history of gender violence in Australia

Violence against women is often represented as a timeless and universal phenomenon, suggesting the problem is too large to fix, or only the worst abuses are worth our attention. Alana Piper and Ana Stevenson explain how understanding the history of gender violence in Australia can undermine this belief.

Content warning: This article discusses domestic violence and may be disturbing for some readers. If it has raised concerns for you, help is available via the UTS Counselling Service (for UTS staff and students) on 02 9514 1177, Lifeline on 13 11 14 or the Domestic violence line (24 hours) 1800 65 64 63. If you have any concerns for your safety or the safety of others on campus please call UTS Security on 1800 249 559 or off-campus please call 000.

SEE MORE: You can read more about our nation’s long history of gender violence in Alana’s and Ana’s book Gender Violence in Australia: Historical Perspectives.

In 2015, the Australian federal government proclaimed that violence against women had become a national crisis. Despite widespread social and economic advances in the status of women since the 1970s, including growing awareness and action around gender violence, its prevalence remains alarming.

Australian Bureau of Statistics data shows that a third of all women in Australia have been assaulted physically and a fifth of all women have been assaulted sexually. In 2016, nearly a fifth of adult women also reported they had been sexually harassed in the past 12 months.

Other statistics show that one woman is murdered by an intimate partner in Australia each week, and family violence is a leading factor in a third of all cases of homelessness.

The resulting strain on government services and lost productivity is estimated to cost the Australian economy around A$13.6 billion a year.

Gender violence seems to have reached a particularly significant moment in Australia. But violence against women is often represented as a timeless and universal phenomenon. This creates the perception that the problem is too large to fix, or that only the worst abuses are worthy of attention.

Yet, as our book Gender Violence in Australia: Historical Perspectives illustrates, understanding how gender violence occurred in the past can provide the necessary context to help respond to the problem today.

Why is domestic violence regarded as a ‘silent’ epidemic?

Family violence and domestic violence are frequently referred to as a “silent epidemic” that is quietly engulfing Australia.

A culture of silence at the individual level means victims are often too fearful or ashamed, and bystanders too uncomfortable or conflicted, to speak out.

This may suggest gender violence was invisible in Australia’s past, or that it was only recently recognised as a social problem. This is not the case.

As Australian feminist historical scholarship began to emerge in the 1970s, historians started to discover a range of source material on the everyday lives of Australian women, including their experiences of family, sexual, and other forms of violence.

Kay Saunders, for example, commented on the “surprising abundance of primary sources” about violence against women when she published her seminal 1984 article on domestic violence in colonial Queensland. Looking for court records on a completely different topic, she had been struck by the frequency of domestic assault cases brought before 19th century courts.

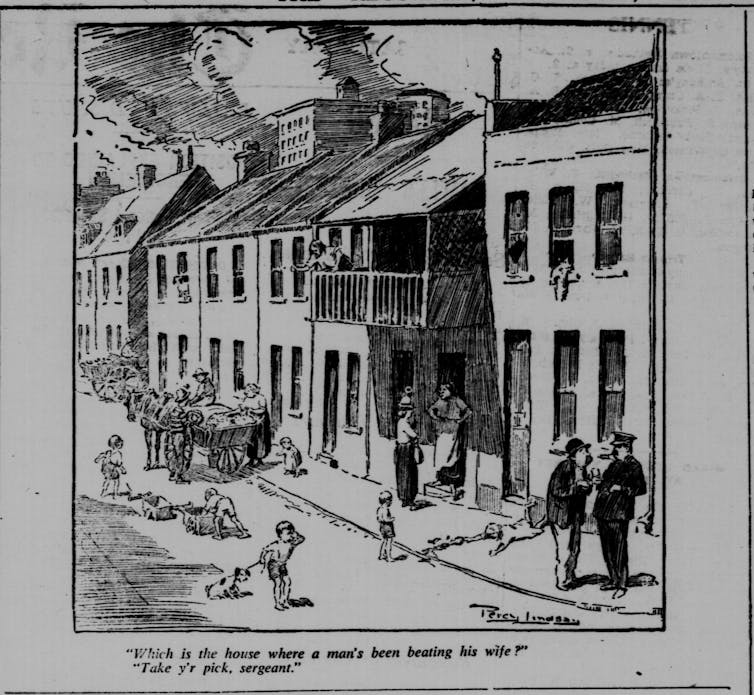

And Australian newspapers made these cases known to the community. The language may have been different – 19th and early 20th-century journalists referred to domestic violence as “wife-beating” – but the issue was far from silent.

A cartoon published in the Recorder newspaper depicting the pervasiveness of wife-beating in Australia in the 1930s. National Library of Australia.

These legacies of Australia’s past contributed to the development of a particularly virulent toxic masculinity that persists today.

Into the 20th century, the belief persisted that husbands had the right to “chastise” their wives’ behaviour, including through corporal punishment. However, there was also a general acknowledgement that unjustifiable wife-beating was a widespread problem.

But then, as now, positive action to confront this problem was less forthcoming than expressions of concern about it.

When it came to sexual violence, there was not only awareness of the problem as far back as the 19th century, but legislative attempts to address it, albeit with limited success.

Historian Andy Kaladelfos points out that Australian jurisdictions were among the first in the world to try to tackle the problem of child sexual abuse within families by making incest a specific criminal offence.

Concerns about sexual violence against women (at least white women), especially on the colonial frontier, also meant that Australian jurisdictions retained the death penalty for rape long after its use was abolished in England in 1841.

However, in most Australian jurisdictions across the late 19th to mid-20th century, only around 56%-63% of men prosecuted for the rape of adult women were convicted. In NSW, this figure dropped down to a mere 32%.

Juries’ reluctance to convict men was due in large part to victim-blaming attitudes that research shows has never disappeared from Australian courtrooms.

Australia's culture of violence

Historically, these attempts to reduce gender violence usually floundered because legislation failed to address the underlying causes enabling this culture of violence.

For instance, Australian society has told men they need to be physically and mentally tough, which normalised male aggression. During the 19th and 20th century, housewife manuals routinely instructed women, as the “gentle sex”, that it was up to them to manage the moods of the men around them.

This implied that a truly “womanly” woman would be able to avert a man’s anger or violence.

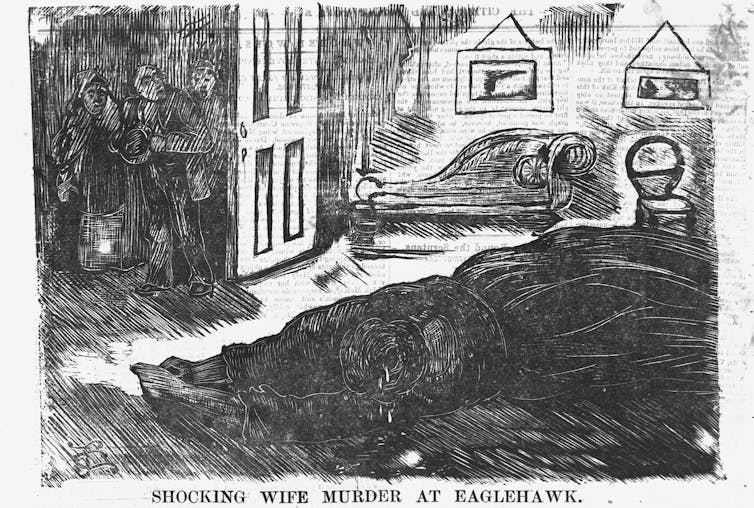

A newspaper illustration from 1877 depicting the body of an Eaglehawk woman. Her husband was charged with her murder. State Library of Victoria

For much of the 19th century, men far outnumbered women within the European population of the Australian colonies. This produced a culture that prized hyper-masculinity as a national ideal.

Historian Elizabeth Nelson reveals that the first world war further embedded these cultural attitudes, exacerbating gender violence during the interwar period.

These legacies of Australia’s past contributed to the development of a particularly virulent toxic masculinity that persists today.

Another key factor was gender-based economic inequalities in early Australian society. Historically, the limited and low-paying nature of women’s work prevented many from leaving men who were abusive to them or their children. When husbands were charged with assaults, wives would often petition magistrates for clemency to avoid the financial ruin that would come if the family breadwinner was sent to prison.

Historian Judith Allen argues that there were two major cultural changes that empowered more Australian women to leave violent men.

One was the decline in family fertility between 1880 and 1920, which meant women had fewer dependants to support in the event of relationship breakdown. The other was the post-war rise in opportunities for paid female employment.

This underlines the importance of recognising how non-physical forms of abuse – such as economic abuse – continue to prevent women from leaving unhealthy relationships.

In a society where men still largely control the economic livelihoods of women, this also perpetuates a culture of sexual violence.

Who are the most vulnerable communities?

Gender violence can affect anyone. But historical legacies have rendered some communities more vulnerable than others.

Frontier violence routinely led to the sexual and economic exploitation of Indigenous women, who became particularly vulnerable to gender violence when isolated from kinship networks.

Again and again, the media has amplified some reports over others. Its sensationalist approach engendered a focus on the almost wholly specious “white slave panic”, an early 20th century phenomenon that cultivated fears about white women and girls being sold into international sex slavery. This increased the stigmatisation of migrant women who did wish to engage in sex work, leaving them prey to exploitative conditions.

Cultural attitudes towards sexuality have also influenced patterns of gender violence. Although the term “homophobia” emerged from the gay and lesbian activism of the 1970s, historian Shirleene Robinson argues it has its roots in the late 19th century.

One outcome of this history is that the media continues to personify white women as a type of ideal victim, while routinely characterising women of colour, the LGBTIQ community, migrant women, and sex workers as culpable for their own victimisation.

Reforms introduced to address gender violence

Women’s rights reformers and feminists have fought hard to pass laws against gender violence in Australia since the late 19th century. These range from arguing for statutes to raise the age of consent in the 1880s and 1890s to criminalising marital rape a century later.

Today, digital initiatives such as Destroy the Joint’s Counting Dead Women project continue this important work.

Historical gains against gender violence in Australia only occurred because of the willingness of some to stand against complacency. The problem will not be solved by the simple march of time. Action is needed.

Alana Piper is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the Australian Centre for Public History at University of Technology Sydney and Ana Stevenson, is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the International Studies Group, University of the Free State, South Africa.

To learn more visit the Australian Institute of Family Studies website. You can also donate funds to Women's Legal Services Australia or to Rape and Domestic Violence Services Australia.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.