Finding balance in hybrid work

The COVID-19 pandemic brought with it some significant changes to how we work, with most workers moving to completely remote work in a tiny window of time.

Image: Pexels

As lockdowns end and we slide back into normality, the question of how we work going forward looms large.

Tech giants Apple and Google both pushed for a complete return to office and received massive employee backlash. Other organisations, like Atlassian and Canva, are leaning into the change and only requiring employees to come to work for a few days a year. Despite flexible working arrangements existing for decades, the concept of a truly hybrid workplace is relatively new, and so there are plenty of questions to be answered.

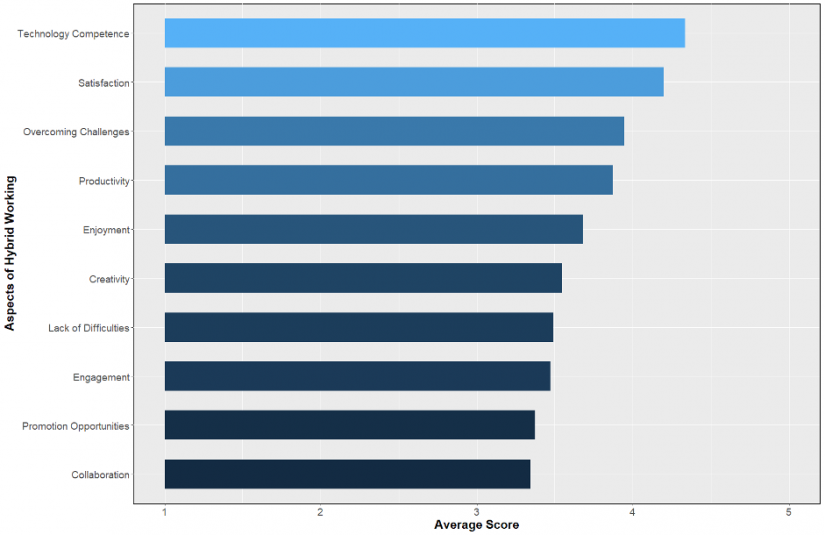

To answer some of these questions, our research team at the UTS Futures Academy conducted a survey among 172 people working in Australia to take a snapshot of the current state of hybrid. The survey asked people to self-assess themselves on 10 features of hybrid work: satisfaction, productivity, enjoyment, creativity, engagement, collaboration, technology competence, ability to overcome challenges, difficulties experienced, and promotion opportunities. We hope the analysis below will help start the conversations between employers and employees about effective hybrid work practices.

How do people feel about hybrid working?

People feel generally positive about hybrid working, but not overly so. All 10 features of hybrid work had average satisfaction levels above three on the five-point scale. Satisfaction with hybrid working and technology competence had the highest average scores of 4.2 and 4.34 respectively. Technology competence had an average well above what we expected considering the rapid technological adjustments most individuals have had to make.

However, the lowest scoring aspects are more informative; collaboration, opportunity for promotion, and engagement all had average scores below 3.5. Somewhat predictably, it seems that the social interactions driving these aspects is lacking in most hybrid workplaces.

Further statistical analysis led us to group four of the aspects into an aggregated higher-order factor we have called HWA Positive. This higher-order group includes ratings of productivity, engagement, enjoyment, and innovation. The average aggregated score for HWA Positive was 3.66. For all further analysis, we have used this higher-order group to simplify interpretation in later analyses.

How much are people working remotely?

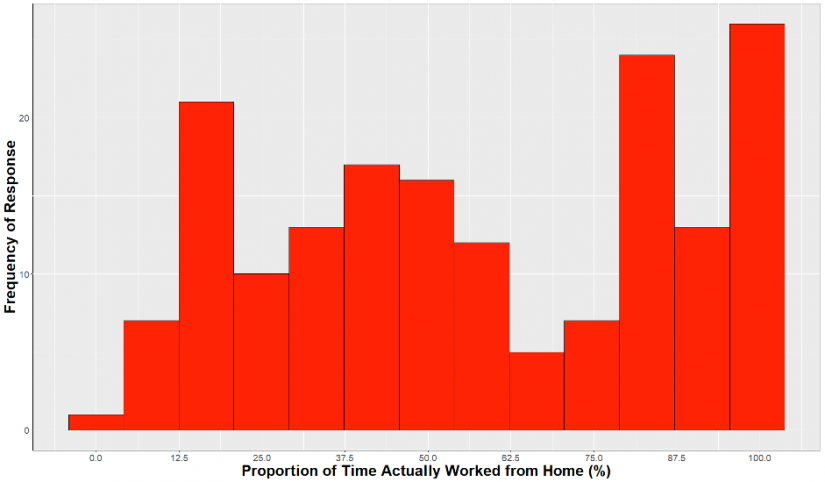

The percentage of time worked remotely ranges from 0 to 100%, with peaks at 20% (one day/week), 80% (four days/week) and 100% (five days/week)

The percentage of time worked remotely may not represent a preference as 67% of respondents were working remotely due to government mandates restricting their access to workplace. At the time of data collection, Australia was in varied forms of lockdown, ranging from almost complete freedom to strict lockdown.

Half of the respondents were working remotely for 55% or more of their total work hours, a significant change from pre-pandemic times when only 24% of people were working from home at least once a week (ABS media release: A year of COVID-19 and Australians work from home more, 17/03/2021).

At the time of writing, 68.5% of the eligible Australian population has had at least one dose of vaccine, meaning the return to pre-pandemic life is approaching. After this taste of remote working, will employees be willing to return to the pre-pandemic lifestyle of commuting to the office five days a week?

How much would people like to be working remotely?

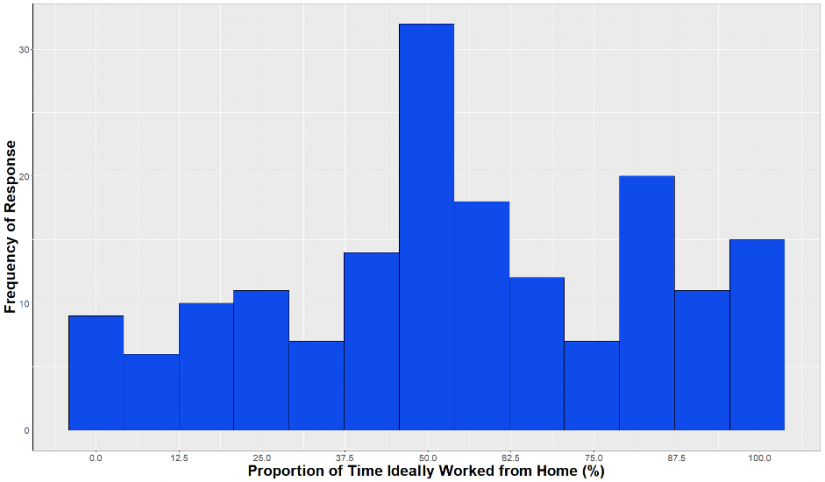

The most common response to the question ‘how much would you like to work from home?’ was to spend half their work hours at home and half at the office. When we consider this response in combination with features that respondents were least satisfied with (collaboration, engagement, opportunity for promotion), it is clear that people still want essential interactions and social bonds that don’t translate well to the online context.

Importantly, only 4.6% reported that they do not want to work at home at all, while 85% of our sample reported wanting to work at home for at least 20% of their work hours. The pandemic has given people a chance to experience a more balanced lifestyle and it appears that the majority of them don’t want to slide back into the old way of working. However, there is wide variance in individual preferences. There are as many people wanting to work from home from 0 to 20% of the time, as there are people who would like to work from home 70 to 90% of the time. This variability of responses led us to examine what happens if you are working above or below your ideal proportion of remote hours.

How does being above or below your ideal hybrid hours affect work outcomes?

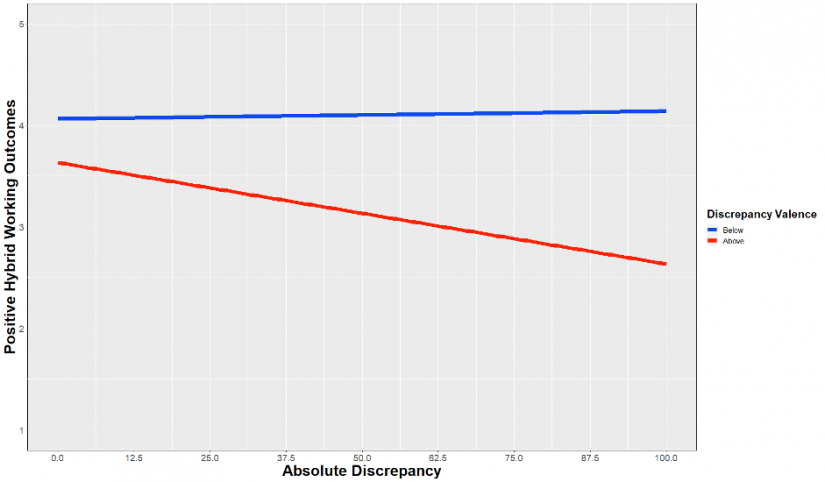

To answer this question, we separated our analysis into two groups of people: those who were working remotely more than their ideal amount (red line), and those who were working remotely less than their ideal amount (blue line). The figure below shows changes in the satisfaction levels with the HWA Positive factor (productivity, engagement, enjoyment, and innovation) as the discrepancy between actual and ideal increased.

With remote working, it appears that too much can be detrimental to productivity, engagement, enjoyment, and innovation. As shown by the red line, the gap between the ideal and actual remote hours worked increased, and the HWA positive rating dropped significantly. Working fewer hours remotely than desired had no impact on satisfaction levels. Given these results, it will be interesting to see how much time employees of companies like Atlassian and Canva, who allow total freedom to work from home full time, spend in the office.

The dissatisfaction with too much remote work may be affected by the fact that it is mandated. Working long hours remotely during lockdowns provides no opportunity for the replenishment that comes from the dynamics of face-to-face social interactions. Social interactions in remote work are more programmatic and, when they occur, are sequential. This contrasts with the more spontaneous, ad hoc social interactions at work, which are dynamic reciprocal.

Takeaways

The introduction of hybrid working has brought many challenges, and there is no doubt that creating an effective hybrid workplace will be one of the most complex problems for organisations in the next decade. The findings discussed in this article demonstrate that the ideal hybrid workplace has a different meaning for each individual. The incumbent, full-time office work, has been defeated and now we stand in an era of change with endless possibility. In a classical political fashion, some radical people will propose that employees should have complete control over their working conditions now, and only come to the office when they choose. But a simple approach like this won’t do; the role a central place of work plays in our life cannot be understated. The passing greetings and water cooler chats can’t be mediated by a company-wide picnic day. As organisations begin to build out their robust hybrid working plans, we encourage employers to include their employees in the conversation. The pandemic has given us a rare chance to implement rapid changes that will completely change the way we work, so let’s make the best of it.

This article is the first in a series on hybrid working. The next article will explore how environmental factors, such as social support, commute time, and children at home, affect how much people want to work from home and how effective they feel when they are there.