In a culture that seeks to make older women invisible, Julie Rrap’s latest exhibit, Past Continuous, is a gloriously defiant statement of self, writes Cherine Fahd.

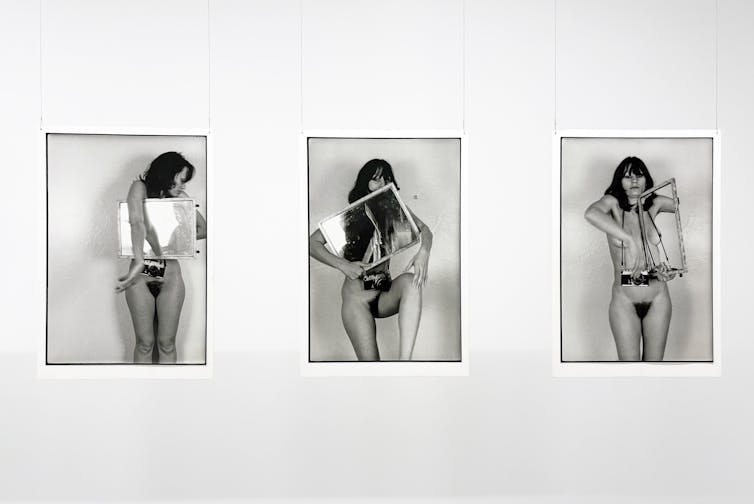

Julie Rrap, Disclosures: A Photographic Construct (detail), 1982, installation view. Julie Rrap: Past Continuous, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, 2024, black and white archival prints, colour cibachrome prints, Museum of Contemporary Art, purchased 1994. Image courtesy the artist and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia © the artist. Photograph: Zan Wimberley.

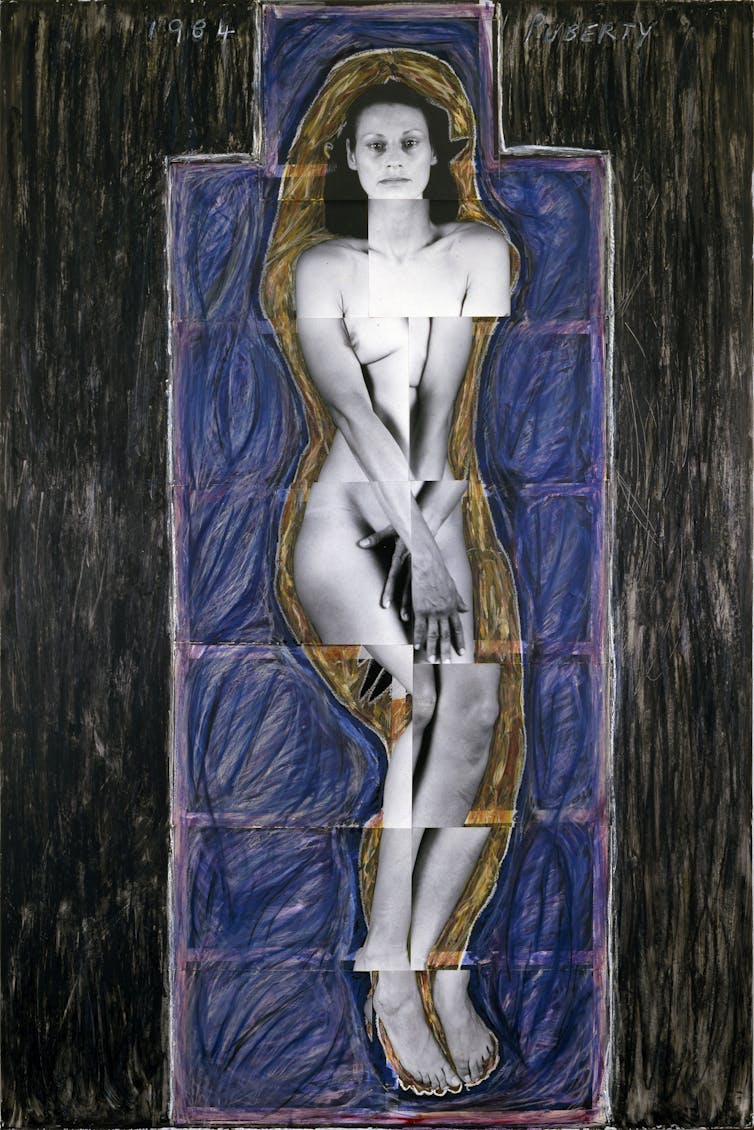

The first time I saw Julie Rrap’s artwork was also the first time I saw Julie. It was 1993 and I was a 19-year-old painting student at the College of Fine Arts in Paddington. Her self-portrait, Persona and Shadow: Puberty (1984), hung at the end of the corridor where I took art history classes. I used to look at the woman in that photograph and think that, despite performing a pose of feminine reserve, she was all-knowing and mighty.

I met the real Julie Rrap in 2012. By then, I was a 38-year-old photo-media artist teaching at Sydney College of the Arts. I thought, “Here is the mythic artist whose work had been a cornerstone of my artistic education, now an everyday colleague.” I told her about my first encounter with her work. She graciously giggled, having been told similar stories by many who had studied her work.

Julie Rrap, Persona and Shadow: Puberty, 1984. Image courtesy the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney © the artist.

Julie Rrap, Persona and Shadow: Puberty, 1984. Image courtesy the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney © the artist.

In 2021, we travelled together to Canberra to see the nine images from Persona and Shadow on show at the National Gallery of Australia. On seeing the iconic photographs of Julie Rrap, by Julie Rrap, with Julie Rrap, I fully experienced the doubling and mirroring effects of her work.

This collision in time, with the artist and her body, is precisely what Rrap’s latest solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Past Continuous, contends with. It features her landmark 1982 installation Disclosures: A Photographic Construct, alongside new works – encapsulating more than four decades of exploration of the female body as a subject and object of art.

The nude comes to life

Disclosures (1982) was a pivotal piece in Rrap’s career. Comprising more than 70 photographs and self-portraits, it undermines the traditional voyeuristic gaze associated with the nude female body. The nude has come to life wearing a camera around her neck, acting as both the photographer and muse in a studio of her own. Rrap points the camera not only at herself but also at us, the viewers.

Julie Rrap, Disclosures: A Photographic Construct (detail), 1982, Museum of Contemporary Art, image courtesy and © the artist. Photograph by Cherine Fahd

Julie Rrap, Disclosures: A Photographic Construct (detail), 1982, Museum of Contemporary Art, image courtesy and © the artist. Photograph by Cherine Fahd

This reversal creates a dialogue between the artist, the camera and the viewer, challenging the objectification of women in Western art. Rrap makes herself the nude, who is alive and writhing with her own creative agency.

The multichannel video work Drawn In (2024) is a companion piece to Disclosures created 42 years later. Rrap reinforces herself as a creator by energetically sketching around her nude body in charcoal – multiple GoPros replacing the older-style camera.

Julie Rrap, Drawn In, 2024, (detail), 3-channel digital video projection, 3-channel audio, phototex, image courtesy the artist, © the artist.

Julie Rrap, Drawn In, 2024, (detail), 3-channel digital video projection, 3-channel audio, phototex, image courtesy the artist, © the artist.

Seeing Disclosures in the context of this newer work highlights the consistency and depth of Rrap’s inquiry. It demonstrates all the ways we can never see ourselves from the perspective of others. No matter how many self-portraits we take, or how much we study our reflection, we get no closer to having an external objective view of ourselves. Rrap has always known how we appear is as changeable as the weather.

The artist and the artist in conversation

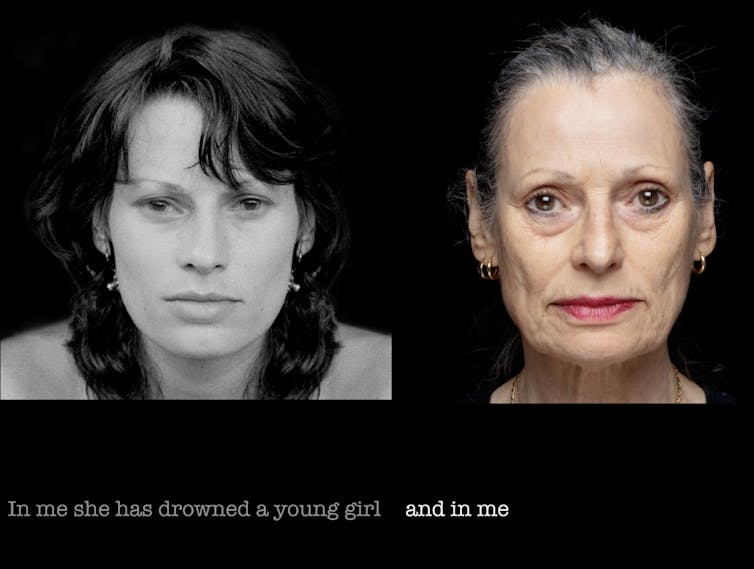

The new works in Past Continuous explore the transformation of the body through time. The video works Time Passing Through Me (2024) and Mirror Talk (2024) create a conversation between the artist’s younger and older selves.

In Mirror Talk, we see the faces of young Julie and older Julie glitching and morphing. We can hear a typewriter beat out the words from Sylvia Plath’s poem Mirror – becoming a language for young Julie, aged 31, to talk to her future self, aged 72. This poetic device issues an affecting tenderness from the present self to the past self and vice versa.

Julie Rrap, Mirror Talk (still, detail), 2024, 2-channel digital video animation, colour, sound, vinyl, image courtesy the artist; Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney; and ARC ONE Gallery, Melbourne © the artist.

Julie Rrap, Mirror Talk (still, detail), 2024, 2-channel digital video animation, colour, sound, vinyl, image courtesy the artist; Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney; and ARC ONE Gallery, Melbourne © the artist.

At the centre of the exhibition is SOMOS (Standing On My Own Shoulders) (2023), a life-sized bronze sculpture of Rrap standing on her own shoulders. To see the body of a woman in her seventies cast in bronze is gloriously defiant and daringly unconventional.

It not only challenges traditional depictions of the classical female nude in Western art as being young and helpless, but also counteracts the cultural hierarchies that privilege the bronzed bodies of naked men above the bodies of older women.

The body as a site of enquiry

In her 70s, Rrap’s decision to continue to bring her own body into view is deliberate and without vanity. There is no softening of the edges or raising of the flesh – and no attempt to erase the marks of time. She stands before us as she is, in her complexity. This is not a body that has been idealised or romanticised. It is real, lived-in, strong and vulnerable at the same time.

Julie Rrap, featuring: Disclosures: A Photographic Construct (detail), 1982, installation view, Julie Rrap: Past Continuous, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, 2024, image courtesy the artist and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia © the artist, photograph: Zan Wimberley.

Julie Rrap, featuring: Disclosures: A Photographic Construct (detail), 1982, installation view, Julie Rrap: Past Continuous, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, 2024, image courtesy the artist and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia © the artist, photograph: Zan Wimberley.

There is defiance in this – a refusal to hide or diminish the reality of a finite human existence. As a young female artist in the late 1990s and a middle-aged artist today, I find Rrap’s use of her own body in her work profoundly liberating. It is an invitation to see my own body not just as a failing object but as an ongoing, changeable medium of artistic and political expression.

Standing in front of SOMOS, I am reminded of the conversations we have with ourselves and the ways we shape and reshape our identities over time. Rrap’s work is a testament to this ongoing process of becoming. It is an invitation to see ourselves not just as we are, but as we have been and as we will be. It is a celebration of the process of self-transformation. And for that I am deeply grateful.

Julie Rrap: Past Continuous is at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, until February 16 2025.![]()

Julie Rrap, foreground: SOMOS (Standing On My Own Shoulders), 2024, bronze, Art Gallery of Western Australia Collection, purchased 2024; background: Drawn In (detail). 2024, 3-channel digital video projection, 3-channel audio, phototex; installation view, Julie Rrap: Past Continuous, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, 2024, image courtesy the artist and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia © the artist, photograph: Zan Wimberley.

Julie Rrap, foreground: SOMOS (Standing On My Own Shoulders), 2024, bronze, Art Gallery of Western Australia Collection, purchased 2024; background: Drawn In (detail). 2024, 3-channel digital video projection, 3-channel audio, phototex; installation view, Julie Rrap: Past Continuous, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, 2024, image courtesy the artist and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia © the artist, photograph: Zan Wimberley.

Cherine Fahd, Associate Professor Visual Communication, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.