Some people think income tax is illegal. It’s pseudolaw, and it’s damaging the legal system.

Image: Adobe Stock / By KerinF

Judges have described it as “gibberish”, “obvious nonsense”, “largely incoherent, if not incomprehensible” and “gobbledygook”.

It involves grand claims like “Magna Carta means you do not need to pay your mortgage”, or “the introduction of decimal currency means income tax is illegal”.

It’s the strange and growing phenomenon of pseudolaw.

Pseudolaw looks a bit like law. It uses legal texts and sounds kind of like something a lawyer might say. But it does not follow normal legal rules.

So where did it come from, and why it is so worrisome?

Where did pseudolaw come from?

Pseudolaw is not new to Australia.

For almost 40 years one vexatious litigant has repeatedly argued Australian bank notes violate the Constitution.

Nevertheless, the COVID pandemic has seen a dramatic increase in pseudolaw claims and a shift in their nature.

During this period the de facto emblem of the pseudolegal Sovereign Citizen movement – the Australia Red Ensign flag – became the defining symbol of anti-government protests.

In our recent study on the phenomenon, we found pseduolaw is being influenced by the US sovereign citizen movement.

What’s the sovereign citizen movement?

The sovereign citizen movement emerged in the US in the 1990s out of several overlapping extremist groups.

Members are largely connected by a shared antagonism towards government and a convoluted and conspiratorial interpretation of the law.

While there are significant variations in beliefs and ideologies among members, in our study, we found they make several common arguments.

Sovereign citizens tend to believe all laws are forms of contract.

Because they did not agree to wear a mask, obtain a driver’s licence, or pay council rates (for example), they are not bound by those laws.

To many in the movement, the government is a corporation and therefore whatever laws it claims to make are illegitimate.

They also believe they can gain freedom by rejecting the corrupt authority of the state.

This leads them to tear up their birth certificates, refuse state ID like drivers’ licences, or enrolment in government programs. They see themselves as free sovereigns or natural living beings.

In confrontations with police and arguments in court they will recite phrases such as “I am a living person” or “I do not consent”, which they believe provide legal immunity.

Some may write their name in capital letters or with dashes, colons, or semi-colons between letters or words to distinguish their natural self from the fictitious legal construct.

Some even create their own common law sheriffs or courts to enforce their laws.

But not only do these arguments not work in court, these beliefs are having an increasingly detrimental impact on our legal system.

Influence in courts and beyond

Our study sought to map the impact of these claims in Australian and New Zealand courts.

We found hundreds of examples, with increasing evidence that Magistrates Courts are becoming overwhelmed by them.

For example, in a Queensland case, Mr Van der Hoorn appealed his conviction for driving without a valid license, registration, or insurance.

He claimed to be “Sovereign Freeman JOHAN” who was appearing as agent on behalf of and as the “owner of the created fictions known as JOHAN HENDRICK VAN DEN HOORN and JOHN HENRY VAN DEN HOORN, being created fictions fraudulently owned and controlled by legal fictions”.

In New Zealand, Mr Niwa sought to avoid his tax liabilities by arguing the debt was owed by an entirely different person.

He explained there were two people involved, “Donald-James of the family Niwa” and “DONALD NIWA (TM)”. Mr Niwa declined to “accept the role of the defendant” and therefore argued he should not have to pay.

Neither Mr Niwa nor Mr Van der Hoorn succeeded. Neither did the hundreds of other applicants we found.

These sovereign citizen style arguments are not only appearing in courtrooms.

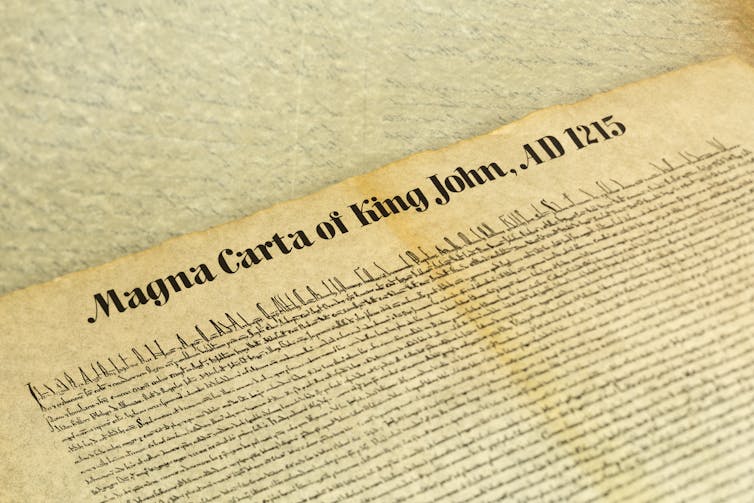

Pseudolegal claims often cite the more than 800 year-old Magna Carta. Shutterstock

Pseudolegal claims often cite the more than 800 year-old Magna Carta. Shutterstock

One recent study found Aboriginal individuals and communities dissatisfied with Native Title processes have begun employing these arguments.

Individuals armed with a false sense of pseudolegal justice are also targeting council, and spread baseless claims about the Voice to Parliament referendum.

Why does this matter?

The rise of sovereign citizen arguments is concerning.

Pseudolaw has a tendency to transform routine and relatively simple legal issues into much more complex and harmful ones that can hurt litigants, their families, and friends, and the legal system at large.

Litigants waste time and money and forego the opportunity to obtain capable legal representation.

It also creates opportunities for scammers and charlatans to benefit from a lack of knowledge about law and government.

These legal arguments also represent the tip of the spear. Sovereign citizens are, occasionally, violent.

How can we respond?

The response to pseudolaw must occur at multiple levels of society.

Courts can reject abusive submissions, and law societies can make clear that some people are simply selling snake oil. But legal responses are limited.

In fact, difficult and expensive legal systems contribute to the growth of pseudolaw. Legal education is costly. Information is behind paywalls. Representation is pricey.

Pseudolaw grew in response to COVID and public health orders that threatened people’s jobs. It grows in response to and as result of unrest, dissatisfaction, and inequality.

Where law and government seems elitist and inaccessible, pseudolaw thrives.

It is free online. You can find it in community groups that provide support and encouragement. That support comes swaddled in misinformation and disinformation.

We need to take pseudolaw seriously. Making the law more accessible and improving civics education is a first step. But the solution will require social, political and economic support as well as legal responses.![]()

Harry Hobbs, Associate professor, University of Technology Sydney; Joe McIntyre, Associate Professor of Law, University of South Australia, and Stephen Young, Senior Lecturer, University of Otago

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.