Western Sydney residents whose homes often get hotter inside than outside during heatwaves have learnt to be resourceful in adapting to the increasing heat write Abby Mellick Lopes, Cameron Tonkinwise and Stephen Healy.

Image: Sebastian Pfautsch/Western Sydney University

Weather extremes driven by climate change hit low-income communities harder. The reasons include poor housing and lack of access to safe and comfortable public spaces. This makes “climate readiness” a pressing issue for governments, city planners and emergency services in fast-growing areas such as Western Sydney.

We work with culturally diverse residents and social housing providers in Western Sydney to explore how they’re adapting to increasing heat. Residents hosted heat data loggers inside and outside their homes.

Last summer was relatively mild, but we recorded temperatures as high as 40°C inside some homes. Recalling a heatwave in 2019, one resident said: “The clay had cracks in the grass that you could almost twist your ankles.”

We correlated these data with what residents and social housing providers told us about managing the heat and what is needed to do this better. Different cultural groups used different strategies. Through the project, residents shared a wealth of collective knowledge about what they can do to adapt to the extremes of a changing climate.

Air conditioning has limitations

Official responses to climate extremes typically rely on a retreat indoors. These “last resort” shelters depend in most cases on a reliable electricity supply, which can be cut during heatwaves.

There have been efforts, but not in Australia, to establish a “passive survivability” building code. The aim is to ensure homes remain tolerably cool during a heatwave (or warm during a cold snap) even if power is cut for a number of days.

We recognise air conditioning is vital for vulnerable populations, including older people and those with health conditions, but we do not want to give up on going outside!

Outdoors, approaches such as pop-up cooling hubs for the homeless are compassionate. While important, such approaches don’t get beyond “coping”.

There’s also a risk of perpetuating a deficit narrative that sees the city’s poorest as lacking capacity to act on their circumstances. Our strengths-based action research approach looks for alternative solutions that draw on the collective knowledge and practices already found in communities.

‘My house is an oven’ – a look at the problem of hot housing in Western Sydney.

How was the research done?

Our project, Living with Urban Heat: Becoming Climate Ready in Social Housing, is part of a broader research program, Cooling the Commons. Its focus is the role of shared spaces and knowledge in designing climate-resilient cities.

We use participatory design methods. Adaptation strategies are developed by working with people who are already attuned to their place and community.

In a first step, to get a better grasp on the micro-climates at each site, residents hosted data loggers in their homes. The data show that the location, degree of urban density and type of housing influence residents’ experience of heat.

In Windsor, for example, the extremes are felt inside the home. Last summer, loggers in Windsor and Richmond recorded 69 days above 30°C. On average, temperatures inside were 6°C warmer than outside and hit 40°C four occasions.

Further east in Riverwood and Parramatta recorded lower temperatures. However, for project researcher Sebastian Pfautsch, these data also highlighted the urban heat island effect. In Riverwood, the average day and night temperatures were 25.8°C and 25.4°C respectively, as brick surfaces hold the heat.

We correlated these data with what residents and social housing providers told us about how they manage heat and comfort in their different places.

A heat data logger installed in one of the homes in the study. Climate-Ready in Social Housing Team

A heat data logger installed in one of the homes in the study. Climate-Ready in Social Housing Team

So how do residents manage the heat?

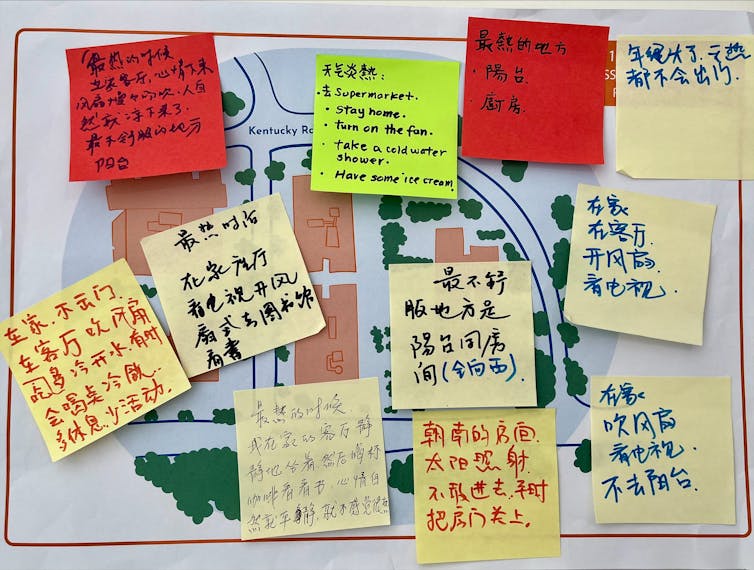

At bilingual design workshops across the locations, themes from the interviews between groups of residents were shared.

Residents who said “I retreat” felt trapped rather than safe in their poorly adapted homes.

“Taking comfort” meant using ice, water spray, sheets and towels to cool spaces and bodies. Chinese residents used foods such as rice porridge congee to cool down. Residents also took comfort from housing providers and neighbours checking on their wellbeing on hot days.

Residents with access to a car “chased the air”. This meant moving between air-conditioned spaces: friends’ homes, coffee shops and supermarkets.

Residents without cars used cool spots, such as public libraries, that they could get to by public transport. Others whose families have lived in the area for decades used their local knowledge to chase the “Dee Why Doctor” and other local breezes, as well as sitting in the river.

Residents often return, though, to a home that has baked in the heat all day.

They had ingenious ways to get air moving with windows, doors and fans. “Making the air” was an important pattern across the groups.

Air movement was as important for bodily comfort as a cooler temperature, particularly for people who found it hard to breathe in the heat. As one participant said: “It’s stuffy in the bedroom. It’s really hard sometimes […] I feel I can’t open the window because of the smells and noise.”

Residents also created “rules” to manage the heat in their homes. These ranged from opening and closing doors and windows at certain times, to keeping lights off, to avoiding baking, to rationing air conditioning.

The groups benefited from sharing these themes. For example, the Chinese community, most of whom did not drive, had never thought of “chasing the air”. On the other hand, using congee to feel cooler was news for others.

In the workshops, different cultural groups shared their experiences of heat and strategies to manage it. Climate-Ready in Social Housing Team

In the workshops, different cultural groups shared their experiences of heat and strategies to manage it. Climate-Ready in Social Housing Team

Collective adaptation works best

In each community, sharing these approaches prompted a broader conversation about more collective forms of adaptation, including shared spaces and practices in the built and natural environments.

This research is raising questions. There is a tension, for example, between the enclosure that air conditioning requires and the movement of fresh air many residents see as healthy. What implications might this have for a cooling hubs blueprint and the future of social housing, particularly where a need for security often means blocked openings and locked doors?

Climate-readiness does not mean reinforcing inadequate technical solutions that shut us in, or barely remedial solutions. These reduce us to what philosopher Georgio Agamben termed a “bare life”, a condition that precludes the possibility of a good one. That need not be so.

Our research is trialling adaptive practices, drawing on local knowledge of cool spaces (both natural and built), and sharing these practices across cultures. It shows we can reimagine climate-readiness as part of a flourishing community.

Abby Mellick Lopes, Associate Professor, Design Studies, Faculty of Design, Architecture and Building, University of Technology Sydney; Cameron Tonkinwise, Professor, School of Design, University of Technology Sydney, and Stephen Healy, Associate Professor, Human Geography and Urban Studies School of Social Sciences/ Institute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.