We can’t rely on consumer spending to keep us recession-free. Shutterstock

The next government can usher in our fourth decade recession-free, but it will be dicey

If we can avoid a recession for another two years, then on July 1, 2021 Australia will have recorded a record 30 years of economic expansion. We will be entering our fourth decade recession-free.

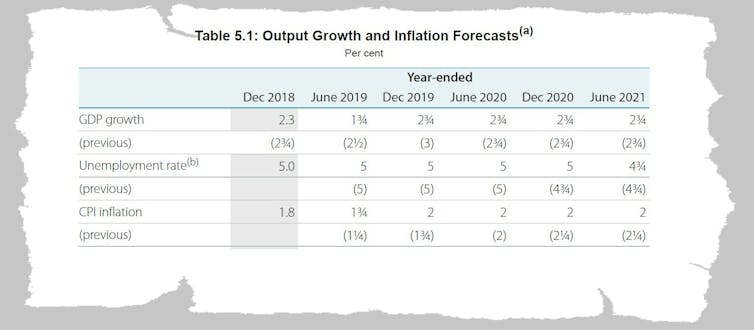

That’s the expectation embedded in the Reserve Bank’s latest set of forecasts in its Quarterly Statement on Monetary Policy. But it will be a challenge.

A major downturn in housing markets, historically low interest rates and an international economy more complex and troublesome than we have seen for decades mean the new government will need to take bold and creative decisions in order for us to achieve this truly remarkable milestone.

Things would be okay globally…

Reserve Bank Statement on Monetary Policy May 2019

The bank has painted a benign picture of the global economic outlook for the next few years after recent data have allayed concerns about a US recession.

The Chinese authorities appear to have stabilised growth in the world’s second largest economy after fears of a steeper decline in activity emerged late last year. Although the Chinese economy faces many challenges, there doesn’t appear to be any signs of an imminent problem.

That should leave economic growth in Australia’s major trading partners at a respectable rate of 3.75% over the next few years, not too different to the global economy. While not exactly a boom, it should be enough to support the Australian economy through to 2021.

This is reflected in the bank’s expectations for the key sectors linking Australia to the world economy. Resource exports are expected to experience strong growth, as are education exports and tourism.

The bank is even expecting manufacturing exports to grow, due to healthy global economic growth and a low Australian dollar. The same can’t be said for rural exports, with drought conditions expected to hurt our international sales for some time.

…were it not for the threat of a trade war

This otherwise upbeat assessment of global economic prospects could come to naught if the renewed trade dispute between the US and China intensifies. Te bank identifies this as a major risk to Australia’s economic outlook.

Even though Australia could benefit from the dispute via Chinese domestic economic stimulus in response to difficulties in moving exports, a continuation of rising protectionist measures would impact us directly and indirectly as global economic growth slowed.

Managing the China relationship in the midst of Trump’s trade war will be critical for the incoming government. A misstep could see China use non-tariff measures to slow Australia’s exports.

It would also make life difficult for Australian companies attempting to capitalise on the opportunities offered by China’s emerging middle class.

In Australia, households are battening down

The Reserve Bank expects employment to continue to grow by enough to keep the unemployment rate stable. However, there seems to be little prospect of a rapid pick up in either wages or inflation that will make a dent in Australia’s household debt burdens.

The bank has made it clear that the very low inflation environment will be with us for several years to come. It expects the inflation pulse of the economy, which appears to have slipped to around 1.5% in the past six months, to only slowly pick up, climbing towards 2% by 2020 and just above 2% (and back into the Reserve Bank’s target zone) in 2021.

That gradual increase is unlikely to be meaningfully outstripped by wages growth, implying either a very small lift in living standards or no increase in living standards. It will result in very low consumption growth.

The bank is forecasting historically weak consumption growth of about 2.5% for the next few years. It will put the high-employing retail sector under pressure.

Reserve Bank Statement on Monetary Policy forecasts, May 2019

Two more rate cuts…

The only good news for households (those with debt at least) is that there is interest rate relief in prospect. The bank uses market pricing for the interest rate assumptions in its forecasts. Markets are pricing a cash rate of 1% over the year ahead, down from the present record-low 1.5%. The bank suggests it will come in twocuts of 25 points.

Even with 50 points of cuts factored in, the bank believes it will only just meet its targets of falling unemployment and 2% inflation. It might have to cut further.

But the effectiveness of interest rate cuts as a way of bolstering the economy is in serious question.

The costs of sustained easy money are rising.

Not only is wealth inequality a potential problem, but as interest rates get lower the banks find cuts harder to pass cuts on.

…but they mightn’t be enough

A major issue for the new government will be to recognise the new-found importance of fiscal policy (spending and tax policy) to support economic growth. It will need to be used in an even handed way, without a hint of pork barrelling. Otherwise it will be wasted.

While lower interest rates will good news for the large proportion of Australians that have mortgages, they will not be great for savers. Whether it is someone saving for a home deposit or someone living off retirement savings, super low interest rates will not make life easier.

This challenging environment for Australian households will have implications beyond just the economy’s performance, making for tricky political waters. Populist political propositions will have much more resonance in difficult times, particularly in regional and rural areas with high retiree populations and the exposure to drought.

The next Australian government should not be complacent.

It will need to adopt an explicit strategy needs to deal with the economic and political fallout from the adjustments within the household sector. it will need to address falling wealth and low real income growth through serious structural reforms aimed at driving up productivity and real wages.

In the short term the government is going to need to be ready to deploy its substantial resources to support households should conditions deteriorate. The low and middle income tax offset are a good starting point.

Business is in good shape so far…

Although business confidence has dropped over the past nine months, the Reserve Bank expects businesses to continue to invest and hire new staff. It expects non-mining business investment to expand at a healthy rate. But this can’t be taken for granted given the precarious nature of consumer demand.

The next government will have to be acutely sensitive to the risk of undermining business confidence. A hiring strike by business would be dangerous for an economy tiptoeing along a knife edge.

We might be surprised by good news. In other advanced economies an unexpected bonus has been strong employment growth despite economic and political uncertainty and modest economic growth.

While this international experience shouldn’t give us confidence that stronger employment growth translate into stronger wage growth, it might at least help maintain consumer spending in the face of lower house prices.

…except for construction

The Reserve Bank is explicit in its expectation that housing construction will turn down over the next two years. The drop off in activity could be big and have a major negative impact on employment. Although there is currently a high level of activity in commercial construction, particularly infrastructure-related activity, it is unlikely to be big enough to offset the downturn in housing construction.

Governments across Australia have an opportunity to think about nation building. Funding costs are low, government finances are strong and the shrinking construction sector will free up labour and other resources for important projects.

Which means its time for nation building

The next term of government will see very little economic momentum originating from consumers. They are in balance sheet repair mode. That makes it the perfect time for the governments to lead the way and drive private sector economic activity through a whole range of long-term investments in Australia’s future.

Coordinating this with the states and identifying the right projects will be the most important challenge facing the new government.

Read more: Australia’s populist moment has arrived ![]()

Warren Hogan, Industry Professor, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.