When Australia’s east coast is caught in the grip of a heatwave, relief can come in the form of abrupt, often gale-force wind changes known as “southerly busters”.

For Sydneysiders, the arrival of the southerly buster is a hot topic right up there with property prices. But in recent years, talk has turned to where southerly busters have gone. The feeling is, they’re not what they used to be.

Our new research shows southerly busters have become more frequent but less intense over the past 25 years. Global warming is to blame.

As the warming trend continues, we can expect more southerly busters to roll in. These winds can damage property, worsen bushfires, and endanger both aviation and marine activities. Unfortunately, we may witness more of these unwelcome effects in the future.

What are southerly busters?

During the warmer months, from October to March, Australia’s southeastern seaboard can experience sudden wind changes known to locals as southerly busters. This is when a hot northwesterly wind turns southerly, with wind gusts exceeding 15 metres per second. A severe southerly buster has gusts of at least 21m/s.

The good, the bad and the ugly

Southerly busters can drop temperatures by up to 20°C within minutes, providing instant relief from oppressively hot days.

But they also produce severe thunderstorms, low cloud, fog and destructive winds. Consequently, they threaten human life and property.

Powerful near-surface wind gusts and associated turbulence disrupt the aviation industry. Takeoff and landing become particularly challenging, as southerly busters can create sudden increases or reductions in aircraft speed and drift.

Large waves and rough seas are hazardous for surfcraft, boats and rock fishers. Marine rescue organisations know and fear southerly busters as they respond to thousands of related emergency requests annually.

What we did and what we found

News reports suggest southerly busters have become far less frequent and weaker in recent decades. Some say southerly busters no longer pose the dangers they once did. But they have not disappeared entirely.

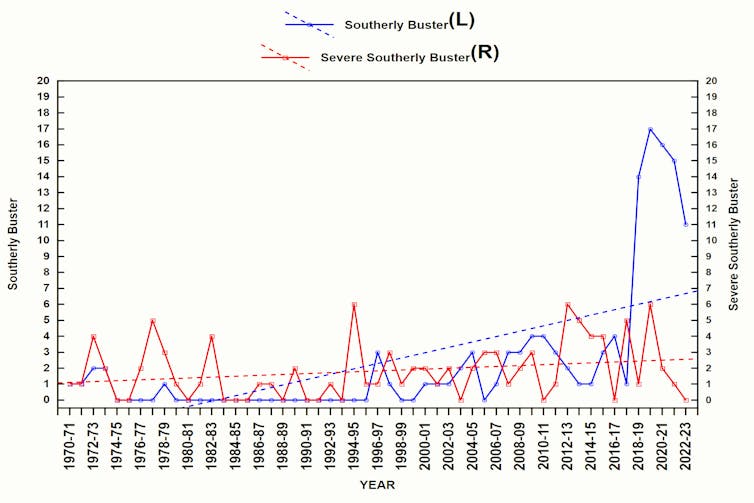

In our new research, we used observational data from 1970 to 2023 to analyse trends in southerly buster frequency and intensity. We were especially interested in the period of accelerated global warming from the early to mid-1990s.

Our statistical analysis considered changes from year to year, from 1970 through to 2023. Then we compared two consecutive time periods, 1970–96 and 1996–2023.

We looked at maximum wind gusts, frequencies of southerly busters compared to severe southerly busters, and the influence of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation.

We found severe southerly busters dominated from 1970 to 1995.

After that, both southerly busters and severe southerly busters gradually increased in number, but the lower wind speed southerly busters became more common overall. So the combined annual total of southerly busters and severe southerly busters increased over time.

From 1996 to 2023, the number of southerly busters each year approached or exceeded the number of severe southerly busters.

The annual frequency of southerly busters increased dramatically in 2017–18 and shot up further still in 2018–22, far exceeding severe southerly busters.

Southerly busters (blue) are becoming more frequent over time, compared to severe southerly busters (red) Leslie, L., et al (2024) MDPI, CC BY-ND

Southerly busters (blue) are becoming more frequent over time, compared to severe southerly busters (red) Leslie, L., et al (2024) MDPI, CC BY-ND

Changing atmospheric circulation patterns

In the Southern Hemisphere, global warming has changed atmospheric pressure at the Earth’s surface just south of Australia. We suspect these changes in cold frontal systems affect both the number and strength of southerly busters and severe southerly busters.

Unusually high pressures just south of the continent push cold frontal systems away from Australia, but the persistent high pressure favours more frequent, though weaker, southerly winds along the NSW coast. That persistent Southern Hemisphere circulation feature has generated more southerly busters during 1996–2023, relative to 1970–95.

On weather charts, the typical sequence is for high pressures over the Tasman Sea to direct hot north-northwesterly winds over the southeast Australian coast, ahead of the Southern Ocean cold frontal system. At the leading edge of the front is the southerly buster, travelling northwards from the southern NSW coast.

Southerly busters in a future warming climate

Global warming-induced large-scale atmospheric circulation changes are responsible for the annual increases of southerly buster frequencies experienced to date.

However, assuming continued global warming, it is unclear how much southern busters will continue to increase. Known southeast Australian climate drivers (El Niño or La Niña) can amplify or reduce the effects of global warming, so any projection of future of southerly busters will benefit from climate modelling studies that focus on atmospheric circulation changes.

With maximum gust speeds significantly decreasing and becoming highly variable since 1996, it is possible southerly busters are becoming shallower. This means they are bringing smaller temperature drops following their passage along the NSW coast.

Implications of more southerly busters

As more people flock to the beaches for relief in a warming climate, they will be increasingly exposed to southerly busters in dangerous surf. Having more frequent southerly busters also raises the risk of wind damage to property and coastal infrastructure.

Coastal airports will need to contend with increased danger to aircraft during take-off and landing. And sudden changes in wind strength and direction will increase bushfire fire danger.

Our research shows southeastern Australia is experiencing more, not less, southerly busters. So we need to prepare for the wide-ranging consequences.![]()

Milton Speer, Visiting Fellow, School of Mathematical and Physical Sciences, University of Technology Sydney and Lance M Leslie, Professor, School of Mathematical And Physical Sciences, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.