From badges to ball gowns: It would have amazed campaigners from 1967 to see people today wearing outfits that overtly describe the movement write Treena Clark and Peter McNeil.

Aboriginal Rights Referendum Rally in Wynyard Park, May 1967. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales and Courtesy SEARCH Foundation, CC BY 4.0

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names and images of deceased people. This story also contains examples of outdated language

During the campaign for the 1967 First Nations referendum, which would go on to receive a 90.77% “yes” vote, the late human rights campaigner Faith Bandler believed fashion and clothing could play a key role in encouraging voters.

A South Sea Islander/Scottish Indian woman, Bandler played a lead role in the 1967 referendum campaign. She described wearing white day gloves when campaigning and speaking to non-Indigenous audiences:

I used to wear short white gloves. They were acceptable to the white community I came in contact with when I was campaigning for black women’s rights. I wore them from 1956 until the mid-1960s. During that period I only ever addressed white audiences. I only had to convince them.

Faith Bandler (second from left) and Harold Holt (third from left) meeting during the campaign. National Archives of Australia

Faith Bandler (second from left) and Harold Holt (third from left) meeting during the campaign. National Archives of Australia

The fashion during the 1967 referendum was conservative. Speakers such as Bandler featured subtle accessories and respectable clothing, occasionally accented by a badge that modestly communicated their message.

It is a far cry from the overt – and often casual – ways fashion is being used in the 2023 referendum campaign.

Subtle style

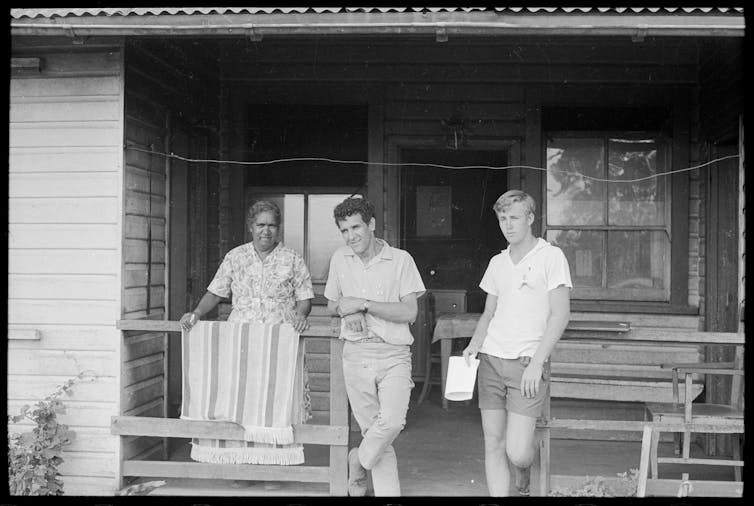

First Nations women, and particularly older women were often the voice of the 1967 referendum, and appearances were important.

Campaigners emphasised respectability and etiquette by wearing structured and formal outfits. Older women wore their Sunday best: dresses with hats, skirts with jacket sets or casual pencil skirts with dressy turtlenecks, and small and subtle jewellery.

The older men wore suits, short-sleeved shirts (with or without structured jackets and slacks) and knitted vests.

In reflecting the changing times and optimism, younger men often wore smart and structured t-shirts with trousers.

Young women chose headbands over hats, knitted jumpers and sweaters over suit sets and large earrings over delicate adornment.

The iconic badges

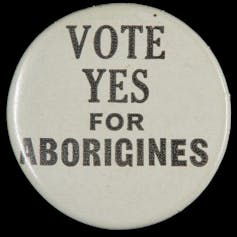

A badge from the 1967 referendum campaign. Copyright Museums Victoria, CC BY

A badge from the 1967 referendum campaign. Copyright Museums Victoria, CC BY

In an iconic photo of the campaign efforts, Ngarrindjeri and Boandik campaigner Shirley Peisley wore a white dress with peter pan collar. Ever so subtly, a 1967 referendum badge is displayed on her lapel. With her hair perfectly coiffed, her only jewellery was a bracelet and wedding ring.

Badges were instrumental in the campaign. They were striking, temporary and expressed an articulate campaign.

Jackie Huggins (Bidjara and Birri Gubba Juru) remembers, as an 11-year-old, handing out badges to promote the campaign.

If I was asked to make one more toffee or lamington for a fundraising drive (or do the hula) or stand on another street corner handing out badges …

Badges have long been used for First Nations political and social statements. In the late 1800s, some First Nations people wore temperance badges as a pledge of abstinence from alcohol.

Returned & Services League and Mothers Mourners badges were significant for First Nations people who served or lost family members in war. These badges were a source of pride of service and mateship.

Members on the Freedom Rides SAFA (Student Action For Aboriginals) wore badges, including in the shape of a boomerang. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales and Courtesy SEARCH Foundation, CC BY

Members on the Freedom Rides SAFA (Student Action For Aboriginals) wore badges, including in the shape of a boomerang. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales and Courtesy SEARCH Foundation, CC BY

For the 1962 Commonwealth Electoral Act, which granted First Nations people the right to vote in Federal elections, tin badges declared “Our Vote = Our Future”. Other badges worn by the 1960s First Nations rights groups featured boomerang shapes and circular Aboriginal rights designs.

Unlike today, t-shirts were not a part of the 1967 referendum campaign. First Nations slogan t-shirts were first worn in the 1970s.

Referendum fashion today

Fashion is again playing a role in the 2023 referendum.

Today, clothes are brighter and more casual. Concepts of “etiquette” have almost entirely broken down.

First Nations designers and artists have shaped textiles and fashion over the decades. Youth and street styles, which often pair text with clothing and make cheeky or ironic gestures, are worn by many.

At a Blak Sovereign Movement press conference, Senator Lidia Thorpe (Gunnai, Gunditjmara and Djab Wurrung) wore an outfit representing cultural pride. Her jacket, pants, and shoes represented the Aboriginal flag colours of black, yellow, and red. Her Treaty t-shirt and Aboriginal flag earrings were strong with symbolism.

Fellow “no” campaigner from the opposite end of the political spectrum, Senator Jacinta Yangapi Nampijinpa Price (Warlpiri/Celtic), chooses a t-shirt with the slogan “Vote No to the voice of division”, often with a conservative blazer.

Mutthi Mutthi and Wamba Wamba woman and Senator Jana Stewart wore a ball gown designed by First Nations label Clothing the Gaps to the Midwinter Ball.

The white silk dress featured the Uluru Statement from the Heart written in black and of different sizes and red embroidered yeses.

The “yes” campaign merchandise of t-shirts, jumpers and badges highlight bright or natural colours as a cheerful and optimistic response to the movement. These are being worn by official campaigners and casual voters alike.

The fashions of the 2023 referendum are very different from 1967. The act of protest incorporated in everyday street wear and evening dresses would have shocked the general public in the 1960s. It would have amazed people to see campaigners wearing outfits that overtly described the campaign movement.

Treena Clark, Chancellor’s Postdoctoral Indigenous Research Fellow, Faculty of Design, Architecture and Building, University of Technology Sydney and Peter McNeil, Distinguished Professor of Design History, UTS, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.