Around the world, an estimated 5 million people pass away with antimicrobial resistant infections every year. As a result, researchers and scientists have been looking for new ways to treat bacterial infections.

“There is an acute problem with antibiotic resistant bacteria. My work focuses specifically on urinary tract infections (UTI), one type of infections where current antibiotics are increasingly less effective ,” says Dr Söderström.

Recent studies show, approximately 80 percent of UTIs are attributed to uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC), a type of bacteria that is rapidly developing resistance to antibiotics.

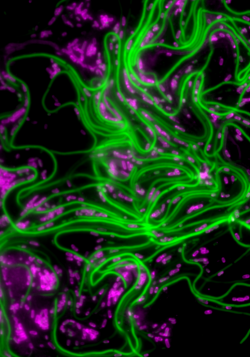

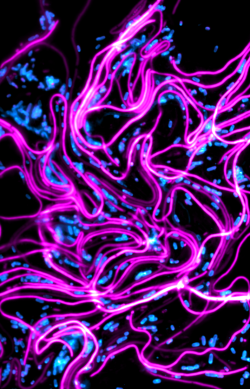

Dr Söderström has put these bacteria under the microscope in a bid to uncover their inner workings. He hopes his research will lead to new ways of managing infections.

Under the microscope

Working as Senior Lecturer and Chancellor’s Research Fellow at UTS, Dr Söderström leads the Microbial Super-Resolution Microscopy Lab at the Australian Institute for Microbiology and Infection (AIMI).

In this role he been using advanced imaging approaches – which he helped pioneer – to investigate how cell shape influences infection and how cells may use ‘shape-shifting’ to fool the human immune system.

“My research goal is to understand how cells transition from rods to filaments and how these two states are different on a molecular scale, for example how their membranes differ," says Dr Söderström.

"I want to understand how to stop these shape transitions as they are vital for continuing the infection.

“This research will help us better understand how to kill the bacteria, and in the long run fight antimicrobial resistance.”

Dr Söderström has already made significant contributions to our current understanding of how bacterial cells go about to divide.

In 2014, he received his doctoral degree in Biophysics at Stockholm University under the supervision of Profs. Gunnar von Heijne and Daniel Daley.

Whilst there he worked on the timing and subcellular architecture of the bacterial division machinery, the divisome, and its main regulator, the FtsZ protein.

Soon after, Dr Söderström packed up his bags and moved to Japan and the tropical island of Okinawa. He accepted a post-doctoral scholar position in the Structural Cellular Biology unit working with Prof. Ulf Skoglund at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST).

In this role, he developed ways to image bacteria in a vertical position using micron holes, that in combination with super-resolution fluorescence microscopy, provides superior resolution of the full division ring in one go.

After a few years at OIST, Dr Söderström packed up his bags again and headed for Australia where he has been continuing his work in this field as a Chancellor’s Research Fellow at UTS.

Becoming a Future Fellow

Dr Söderström is one of only three UTS researchers who have been selected to receive funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC) Future Fellowship 2023 scheme.

The scheme is run by the Australian government and each year leading mid-career researchers hope to secure funding to support works that have national or international impact.

“This funding has come at a great time, now I will be able to continue my work and expand my research team within my institute at UTS. I’m very grateful to the ARC for giving me this fantastic opportunity ” says Dr Söderström.

The funding will be used to further his research program and will enable him to perform more experiments.

“Running infection experiments in the lab can be quite expensive. So, this funding will allow me to conduct more experiments, develop new innovative approaches as well as taking on new students,” says Dr Söderström.

His plans include taking on at least two additional PhD and honour students.

“This funding will also enable my team and I to go to conferences and present our work to the scientific community both on a national and international level. It showcase UTS on the international stage and interested parties from around the world can get a taste of what we are doing.

"My hope is that this will spark new collaborations," he says.