‘We need to restore the land’: as coal mines close, here’s a community blueprint to sustain the Hunter Valley.

Shutterstock

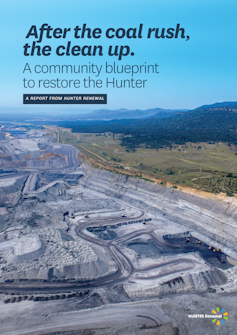

The decline of the coal industry means 17 mines in the New South Wales Hunter Valley will close over the next two decades. More than 130,000 hectares of mining land — nearly two-thirds of the valley floor between Broke and Muswellbrook — will become available for new uses.

Restoring and reusing this land could contribute billions of dollars to the Hunter economy, create thousands of full-time jobs and make the region a world leader in industries such as renewable energy and regenerative agriculture that improves soil and water quality and increases biodiversity and resilience. But to unlock these future opportunities, we must first clean up the legacy of the past.

The Hunter community blueprint is out today. Author provided/Hunter Renewal

Last year community organisation Hunter Renewal asked people across the Hunter Valley about their priorities. They told us they want the Hunter to become a thriving natural environment, a more vibrant and attractive place to live with connected communities, and a diverse and resilient economy.

These community priorities, and their implications for land use planning, are outlined in a report published by Hunter Renewal today: After the coal rush, the clean-up. A community blueprint to restore the Hunter. This blueprint could be a model for other Australian communities planning their transition away from fossil fuels.

How were priorities identified?

We began by analysing more than 170 documents from government, academia and industry about post-mining land use, planning and related issues. From this, a first draft of principles and recommendations for action was created.

The draft was put to a panel of ecological, social and technical experts from the University of Newcastle. Wanaruah/Wonnorua Elders and other First Nations peoples also advised on this draft.

Hunter community members then reviewed and revised a second draft through a series of workshops, interviews and an online survey. They included land holders, students, business owners, mine rehabilitation experts, Indigenous knowledge holders and renewable energy workers.

Rehabilitation and restoration

Hunter residents want mined lands to be restored to support biodiversity and clean industries such as regenerative farming, renewable energy, and other industries that regenerate rather than extract.

To ensure this restoration happens, stronger legal obligations would ensure mining companies cannot walk away from their obligations, leaving voids in the landscape that become a perpetual hazard to human and environmental health. As one resident said:

Mining companies shouldn’t be allowed to have a free pass at everything and get as much funding via subsidies as they do from the government.

Planning and governance

People said that for the Hunter landscape to be restored at the scale required, planning and policy mechanisms will have to be well co-ordinated. An independent and locally based Hunter Rehabilitation and Restoration Commission could do this. It could work alongside the already proposed Hunter Valley Transition Authority.

The community suggested increasing coal-mining royalties to pay for this co-ordinated work. Mining companies would then be the ones that foot the clean-up bill.

In NSW, the royalty rate for open-cut coal is just 8.2% of the resale value. That’s too low for what is required. As another resident said:

We shouldn’t underestimate the size of the task and true cost and effort of rehabilitation of multiple large mines over decades. This is an opportunity to repurpose the land and the physical and social infrastructure.

Community involvement

Successful mine closure and relinquishment requires that affected communities and stakeholders are meaningfully involved at every stage of planning and implementation. Yet true involvement is rare

People in the Hunter want to see greater community involvement mandated to ensure new developments benefit their communities for the long term. As one Hunter resident said:

The mines have privatised all the profits and socialised all the costs […] We want to be involved from the beginning as equals.

First Nations

In Australia all mines are on Indigenous land and over 60% of mines are near to Indigenous communities. Yet Indigenous people are less likely to benefit economically from mining operations than non-Indigenous people.

Hunter residents said this needs to change. One way to do this is to return mining land to Traditional Owners, especially unmined buffer lands.

Making decisions with First Nations people from the outset for new projects will help to overcome the systemic disadvantage in Australia since colonisation. It will also build a knowledge base for change. As one Hunter resident said:

There is so much to be gained in recognising and understanding the land management practices of the local Aboriginal people, based on 60,000 years of observation and science dealing with the oldest continent on the planet.

Climate and environment

Plants and animals need connected ecosystems that allow them to move, adapt and survive. People in the Hunter want a region-wide system of biodiversity corridors. The transition from coal is an opportunity to set up a system that will give the region’s native species a fighting chance in a warming world.

As one resident told us:

Rehabilitating the land to ensure biodiversity is restored is the most important thing to ensure the native plant species can grow back and allow the native animals to return. We need to restore the land to try and reverse the human impacts on the site as much as possible.

Dawn of a cleaner future

The coal industry has had it pretty good in this region for generations. We need a focus now on cleaning up the mess so a new, cleaner future can emerge. This requires a new approach to planning and development in partnership with local communities.

The consultative approach behind the Hunter community blueprint demonstrates the value of including a wide range of perspectives in planning for a post-coal future.

What this set of prioritised recommendations shows is that the people of the Hunter understand the complexity of the task and want to be part of planning it. It will require new laws and well-resourced public agencies capable of managing restoration and ensuring coal companies pay their dues and clean up after themselves.![]()

Kimberley Crofts, Doctoral Student, School of Design, University of Technology Sydney and Liam Phelan, Senior Lecturer, School of Environmental and Life Sciences, University of Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.